May 29, 2018

One knot of speed may not seem that fast…

But when you’re standing atop a forty six foot sailboat that is being pushed along completely sidewise by a thirteen knot wind in a channel of water not more than one hundred feet wide, it seems far, far too fast.

*****

We had already taken the dinghy ashore the day before in order to take a look around and pick up some much needed provisions.

Spanish Wells was picturesque. A small community with immaculately tended yards and gardens, well kept houses which all appeared recently painted with bright and cheery colors and planter boxes in the window, it had a very sleepy but approachable feel to it.

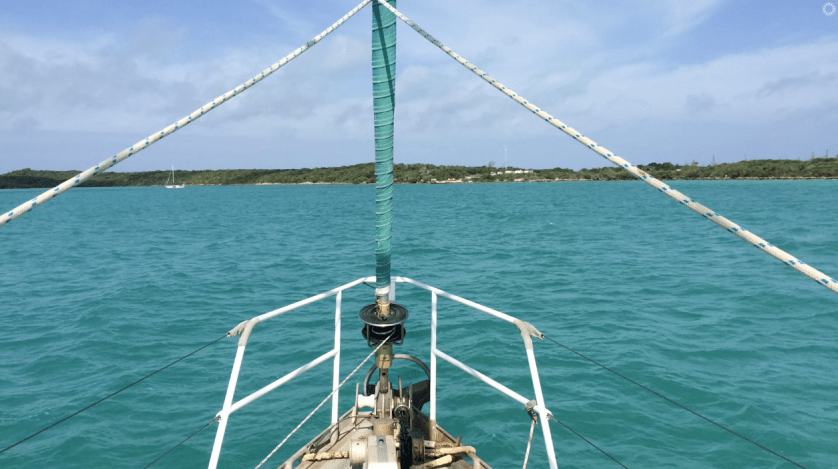

Our five days at remote Little Egg Island had been spectacular, but incoming squalls and shifting winds had eventually forced us to move to Royal Island, which offered better protection in exchange for uninspiring scenery. It made sense to head for Spanish Wells as the weather settled.

We also needed to suss out the marina situation, as we were almost out of fresh water (our rain catch efforts had proven all but fruitless since leaving Georgetown) and we also wanted to top off our diesel tank.

From where we were at anchor, the approach to town required us to navigate inside of a very narrow channel, not more than one hundred feet wide and approximately half a mile long. Depths of only a couple of feet awaited anyone who strayed outside of either side of the channel.

Once at the island, the narrow channel continued, with the town hugging the water’s edge on the right. Eventually, as the town dwindled away on the right, the channel began to grow more narrow and shallow, eventually offering access to only small power boats.

The dock that we could fuel up at didn’t have water and the marina that had water didn’t have fuel which meant two separate stops… not ideal.

We have learned again and again that our highest stress levels and and greatest risk are achieved docking Exit.

The mindset of many boaters is that docks are the safest place to be. Any problem… get me to a dock and all is well again. A sanctuary that offers protection and connection with the world.

For us this couldn’t be farther from the truth.

In fact, in our opinion, docking is nothing more than a conscious and intended (though controlled) collision with something hard… something we try to avoid, as a rule, if at all possible. If there’s any way we can accomplish a task without putting Exit in direct contact with a solid object, well then, that sounds like the preferred method for us… every time.

Water and fuel are the two necessities that sometimes require us to forgo this train of thought. Lugging five to six gallon jerry cans (plastic jugs) by hand via the dinghy is sometimes an option, but simply is not very practical if we need 200 gallons of diesel and/or 200 gallons of water.

The threshold at which tying up at a dock to accomplish this outweighs the effort involved in small quantity transfers utilizing multiple trips is obviously not absolute. However, I can say without any hesitation, that threshold seems to increase after almost every docking experience… even the smooth ones seem to age me rapidly!

Our situation at Spanish Wells was such that we needed almost 200 gallons of water and the dinghy ride was nearly two miles each way.

We like to think that we are constantly evolving into wiser and more savvy sailors/cruisers with every passing day we live aboard Exit. We had purchased two six gallon water jugs while at Georgetown so we could fill up every time we docked at the public dock (which also had what seemed to be the Bahamas only free of charge potable water spigot on the dock).

However, now, with only two six gallon containers aboard, the math indicated it would take us fifteen trips to fill up our fresh water tanks… a total of thirty miles in the dinghy… not very realistic. And putting just a bit of water in the tanks didn’t make sense as water sources here can be far and few in between (with the next one possibly being even more difficult than the last).

Which left us one option… a controlled collision with a solid object… docking. Poop.

Our approach to Spanish Wells in the Mothership, the half mile long hundred foot wide channel, should have been interpreted as the litmus test towards whether we should proceed or abort.

As we entered the channel, a massive ferry appeared from the opposite direction. Thankfully, it stopped just before committing at the other side, allowing us to pass by.

We continued with the intention of stopping at the fuel dock. It should have been a pretty straightforward docking except for the thirteen knot winds coming from our port side. The narrow stretch of land covered with trees to our left helped to buffer the wind; however, the sailboat that pulled up to the fuel dock moments before we arrived left no alternative.

With the limited space to maneuver and winds to contend with, there was no way we could hold position until they pulled away so we continued on, at least temporarily aborting the less critical fuel fill.

With Kris stoically at the helm, we pushed on until we neared the marina dock that had the water we had really come for.

As we approached, we hailed them on the VHF radio. They verified where we needed to tie up and confirmed that someone would meet us on the dock to help with the lines. As the dock grew nearer and nearer, we could see where we needed to go, but there was no sign of the dock master. This would be an unassisted effort.

Both fenders and dock lines were already in place, something we learned early. However, the exact placement of fenders on the boat is always something that can be a bit tricky to determine, based largely on the layout and construction of the dock.

This dock was not very boat-friendly. And dock construction is a make or break prospect… literally.

It amazes me how many docks seem to be constructed with very little regard for the boats for which they are intended.

Well thought out docks (obviously by people with boats, or at least knowledge of them) utilize materials and construction designs which are forgiving to boat hulls and minimize risk of damage.

Some of the best are floating docks, which raise and lower with the tides, offering a consistent height. A dock platform sitting higher than a boat’s decks negates the effectiveness of using fenders, which should really be attached at the hull of of the boat. Boat owners that tie off their fenders to the stantions or lifelines are simply begging to have their stantions torn off if the fenders get snagged.

This risk of fenders getting hung up on something is greatly increased when the outside edge of the dock is not in a straight line, usually due to a dock designed with it’s support posts extending beyond the dock platform.

As a boat reaches the dock, any remaining forward momentum allow the posts grab the fender as it passes. If you’re lucky, the fenders squeeze around the posts. If you’re unlucky, the ropes tying the fenders to the boat snap. If you’re really unlucky, the fenders stop short and the ropes hold; but the stantion or lifeline you were foolish enough to secure the fender to get ripped right off the boat.

Oftentimes the posts are a bigger diameter than the fenders, which means the fender really is of very little benefit. It either catches on the posts, or, between posts, dangles ineffectively a few inches away from the dock edge while the boat’s hull scrapes alongside the posts.

In addition, some sort of bumper system or padding installed on the dock’s edge indicates that the marina taking your money is somewhat concerned about your boat’s well-being.

At the very minimum, rope wrapped around the exposed posts provide some protection. Rubber bumpers are a real blessing, though some curse the black streaks they can leave on the boat’s hull. I’ll take the streaks any day.

In this case, there was nothing.

With an aluminum hull, we generally fair much better than a boat made of fiberglass when it comes to damage caused by docks.

However, the sure sign that a dock was constructed by an idiot is when the dock supports extend beyond the platform, AND the big bolts which hold everything together aren’t even countersunk into the wood of the support posts.

This sadistic approach results in diabolically exposed domed stainless steel bolt heads lurking on the side of the post facing the boat.

Despite the wind and absence of anyone to assist at the dock, Kris cooly performed a textbook docking maneuver, and we glided slowly up alongside the dock.

Unfortunately, the dock was built by an idiot.

As I tried to get a line secured around one of the posts, and push off so we didn’t end up with our bow (and anchor extending just forward of the bow’s edge) pushed into the exposed support posts by the wind, a sickening scraping sound emitted from twenty feet behind me as the midship section of our hull slid alongside one of the posts farther back.

It was the unmistakable sound of metal on metal… the head of a bolt grinding along the side of our hull…

Fuck.

We had just been tattooed by, the ironically named, Yacht Haven Marina with a vicious, and permanent scar to remind us of the day. (Sidenote: Lashing wooden 2x4s to use as rub rails between our fenders would alleviate a lot of the problems with problem docks… however, that system is only beneficial to the boat that already has them set up prior to needing them…).

Shortly thereafter, the dock master sauntered up. A nice guy, and certainly not involved in the marina’s dock design; so we decided to refrain from a commentary and chose to just get our water and get the hell out of there.

Fifteen minutes later, with water tanks once again holding their two hundred gallon capacity, at a cost of fifty cents per gallon, we were ready to head out.

The wind was going to make things challenging. But, we felt, with the assistance of a push off from the dock master, we could edge over to the other side of the channel utilizing the small opening to a stream.

As long as we didn’t go too far and run aground, we concluded that there should be room to back up and turn around in a dicey three-point turn, getting us going back in the other direction, as the channel ahead narrowed and shallowed, which eliminated the option of simply continuing forward much further.

That was the plan.

What we didn’t count on was the thirteen knot wind, buffered by the island and tree cover still to our left, would be funneling straight down through the opening created by the stream to our left. So, while we able to successfully get off of the dock, as soon as we approached the mouth of the stream the wind immediately began to intensify.

Kris managed to get Exit perfectly positioned at the mouth of the stream without touching bottom. But as soon as we stopped, as she started to back us around, the wind caught our bow and began pushing us around much more quickly than we could react.

She couldn’t power forward, as we were still too close to the bank opposite the marina dock, and the wind was shoving us sideways until we were almost broadside in the channel.

Without bow thrusters (to push the boat from side to side), forward momentum was the only thing that would give us steering. And with the channel only one hundred feet wide, we were going to run straight into the dock we had just left before gaining that momentum.

As Kris struggled to bring us about, the wind continued to push our bow around until, before we knew it, we were broadside in the channel, entirely at the mercy of the wind.

One knot of speed may not seem that fast…

But when you’re standing atop a forty six foot sailboat that is being pushed along completely sidewise by a thirteen knot wind in a channel of water not more than one hundred feet wide, it seems far, far too fast.

“Shit…shit…shit…” emerging from Kris’ mouth in the cockpit.

“Fuck…fuck…fuck…” emerging from my mouth on deck.

The dock master, helplessly watching from the dock, trying to yell out and signal suggestions.

As we begin drifting, a man on a power trawler tied up in a slip on the next dock down, pokes his head out and, peering at us, asks “Are you trying to dock here?”

To which I respond, “No, we’re trying to turn around.”

All he can say is “Oh.”

…surreal.

With everything unfolding both in slow motion and high speed simultaneously, I can only stand on the deck and watch.

In a moment of sheer determination and brilliance, Kris manages, with a combination of wheel turns as well as forward and backward gunning of the engine, to regain control of Exit, bringing us fully around so we are finally facing the correct direction.

I realize I have stopped breathing, instantly aged a number of years, and quite possibly just shit myself.

As our heart rates slowly began to drop, and the color in our faces began to return, we looked at each other, fully realizing just how close we had come to disaster. Just the day before there had been a multi-million dollar mega-yacht tied up along the outside edge of the next dock down, which we had just nearly missed.

Still shaken by the dock departing fiasco, we continued down the channel until we, once again, found ourselves at the fueling dock.

We looked at each other and, without any need for discussion, both mutually declared that there would be no more docking attempts that day.

Screw the fuel.

Without slowing, we passed by the fuel dock and pressed on, wanting only to get back to our anchorage.

But Spanish Wells was not finished with us yet.

As we reached the edge of town and prepared to enter the narrow entrance channel, a mahoosive mega-yacht pulled into the channel at the opposite end and started steaming down the center towards us.

Undoubtably, there was no room for us to squeeze by.

We immediately slowed. We were at a spot that opened up much wider with mooring balls and a couple of boats to the right of us, just before the the channel bottlenecked back down, so we tried to tuck ourselves to the side, allowing room for the Mega-yacht to pass.

But we were now clear of the stretch of land and tree cover opposite the town. With no further protection from the winds, now coming from our right, as we came to a stop Exit’s bow once again began to immediately drift to the left pushing us sideways.

We momentarily contemplated trying to grab a mooring ball to hold our position, but we really weren’t prepared or well positioned for that, so Kris said to hell with it and just let the wind carry us fully around until we had come about one hundred eighty degrees, facing the town again.

Exasperated, we powered up the engine and found ourselves once more heading into town, past the fuel dock for a third time.

Fortunately, there is a second channel to and from town on the left, located between the fuel dock and the marina we had gotten water at, so we ducked out of there opting to take a longer route back to our anchorage.

As we departed, we unleashed a string of expletives directed at the Mega-twat, which it turned out, took the exact same course. It turned out they had cut through town only to avoid navigating this longer route around.

Eventually we were back at anchor with two cold therapeutic beers in hand.

Our final assessment of Spanish Wells… beautiful in appearance but rather dark beneath it’s surface.

We subsequently learned that Spanish Wells used to prohibit black Bahamians from being on the island after dark. I don’t believe this is still the case but am unsure when the practice was discontinued. Apparently, the white population of Spanish Wells is comprised of five family names and three hundred years of inbreeding hasn’t helped.

Speaking with the white locals, at first we couldn’t place what initially seemed like a very strange “cajun sounding” accent. Eventually, it dawned on us that the accent we were hearing sounded incredibly South African.

Further research uncovered numerous references to Spanish Wells racism (both historical and prevailing).

The one conclusion we drew with absolute certainty… those visiting Spanish Wells via a boat not equipped with bow thrusters are vehemently advised to do so by dinghy.

And if you take the Mothership in, be exceptionally wary of the dreaded Yacht Haven tattoo.

As for us, an increase in our inventory of fresh water jerry cans is in the very, very near future!