January 18, 2022

…three cleats were torn out of the boat and one of the lines actually snapped. The monohull was slammed into the cement wall of the Canal lock after careening off the catamaran it was rafted up with.

Not the kind of story you want to hear just before commencing on your first Panama Canal transit aboard your own sailboat.

I remember in elementary school, just prior to walking onstage with the rest of my class to sing in our dreaded Christmas concert, being warned by the teacher not to lock your knees while you stand on the bleachers as it can cause you to pass out. At the time, this seemed like the words of a wise and concerned person. Throughout the concert I consciously reminded myself to keep my knees slightly bent.

I also remember, later in high school, just prior to giving a speech in front of all my classmates, being warned by a classmate that it was possible to become so nervous that you could actually puke right in front of everyone, mid sentence. At the time, this seemed like the words of a complete asshole. Throughout the speech I subconsciously reminded myself I might throw up at any moment.

Now, as I walk down E Dock of the well familiar Shelter Bay Marina towards slip number forty-eight in which Exit sits quietly, I struggle to decide two things: 1] whether or not to pass on to Kris the ridiculous story I have just been told and, 2] whether or not the person I just spoke with qualifies more as wise and concerned or a complete asshole.

We are only days away from our own first transit of the Panama Canal and one of the other people on E Dock has just stopped me and asked if I heard about the accident concerning two boats transiting the Canal? No.

A Shelter Bay staff had just relayed a story to him concerning two sailboats which had departed from Shelter Bay Marina a week ago transiting the Panama Canal, one a catamaran and one a monohull. The two sailboats were rafted together inside one of the Canal locks with lines running up to the top of the lock walls, when apparently the massive cargo ship just in front of them gunned its engines too hard as it began to move forward out of the lock, sending a fifteen knot wave of prop wash into the tiny sailboats. The resulting maelstrom actually snapped one of the four lines and ripped three cleats completely out of one of the boats, sending the monohull careening first into the catamaran and then ultimately smashing it up against the cement wall of the lock.

Thanks for that… good to know.

The Panama Canal had become somewhat of a nemesis for us. It was the last thing still separating Exit from an entirely new world, and seemingly endless possibilities… the Pacific Ocean.

We had been in the Canal’s proximity approaching two years now, yet we hadn’t been able to utilize the forty five mile passage connecting the two oceans.

Pandemic…

Repairs…

Parts…

Weather…

There always seemed to be something standing between us and a clear passage.

Not to mention the ever-present population of massive cargo ships and intimidating lock systems occupying the Canal itself… factors that would typically warrant our absolute avoidance.

Now, after all of the experiences aboard Exit – nearly five years and eleven thousand nautical miles – we finally found ourselves poised to transit the Panama Canal and reach the Pacific Ocean.

Having committed to the final process of physically measuring the boat and being assessed by the Panama Canal Authority, as well as having paid over two thousand dollars in fees, we were given a sixty day authorization to schedule the actual transit date.

Still, the one absolute nearly five years and eleven thousand miles aboard Exit had taught us was that schedules set in stone are the most fragile.

Despite our deadline, we had decided we were not willing to cross to the Pacific without our genoa furler in working order, and that ended up taking longer than two months to sort out. Fortunately, we didn’t incur extra costs (or get bumped altogether) when we exceeded the sixty day limit set forth by the Canal Authority policy.

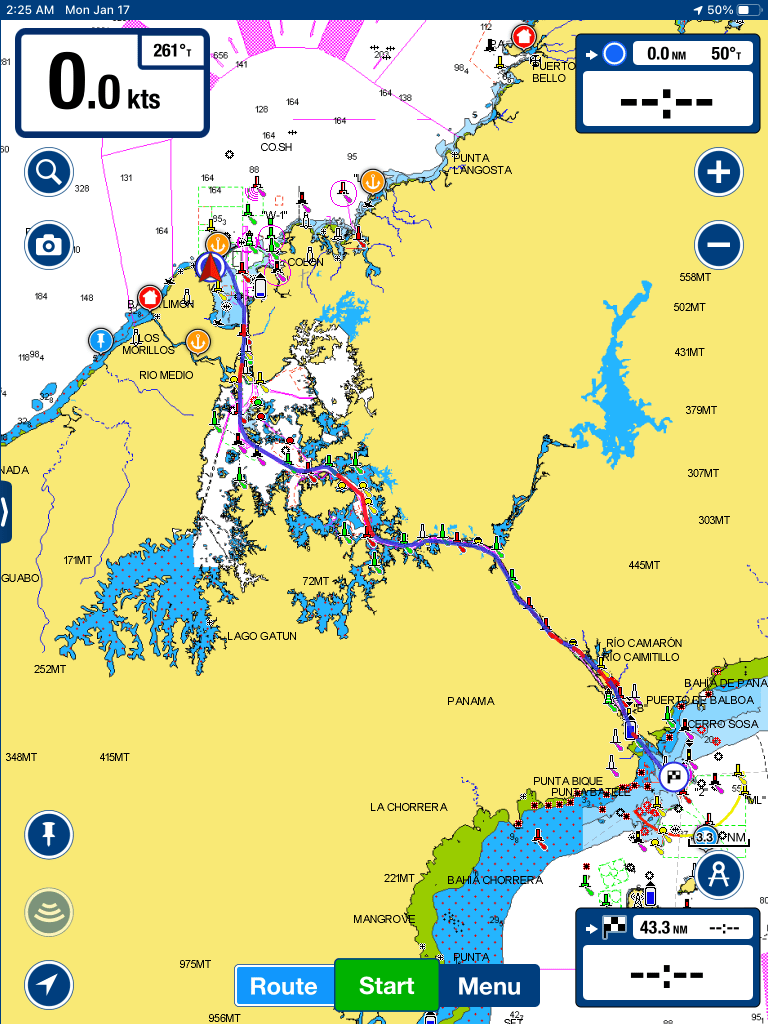

Finally, the stars aligned and the date was set. January 17 departing Shelter Bay Marina; arriving in Panama City January 18. The transit would last two days.

The Process…

The Panama Canal is blah…blah…blah. Way too much to go into. For background…

Google? Alexa? Hit it.

Otherwise read on. [And now, back to our pre-recorded show…]

It was now only days before our scheduled departure.

Exit was ready. She was fully provisioned. Diesel tanks full. Petrol tanks full. Propane tanks full. Water tanks full. We had just learned we were scheduled to transit with another monohull currently in the marina – S/V Swiss Lady. We hadn’t met them.

Despite everything being in place, we couldn’t escape the anxiety. Excitement and fear… an old friendship.

Kris’ stress levels were also through the roof regarding our culinary requirements. Never before had we even had five other people aboard Exit at once, much less had to feed them. During a passage. Through the Panama Canal. Amongst gigantic cargo ships. What’s to stress about?

Now, as I’m walking along the dock back to the boat, one of the other boat owners has stopped me and told me this crazy story of mayhem and chaos in the Canal. No advice, like you would expect from a wise or concerned person. Just stirring things up… like you might expect from more of an asshole.

Perhaps foolishly, I choose to tell Kris the story. She’s not impressed.

At least we know our cleats won’t pull out.

Of the four line handlers required to be aboard during our transit through the Canal, two are being provided by the agent we have been using to arrange all the transit logistics. We are providing the other two.

Juan, a Colombian we had befriended living on his own sailboat in the marina back in June, had already offered to assist us. He had experience transiting many times so we took him up on his offer. When we decided to get a fourth outside line handler to further take some of the workload off us, instead of me filling that role, Juan recommended one of his friends who also had experience.

Three days before our scheduled transit date, Juan indicated casually that his stomach was bothering him a bit.

A day later, he indicated he had started taking some pills.

On the day before we were to depart, we saw him outside his boat. He said he was starting to feel much better… no problem.

Everything was a go.

We couldn’t have been more nervous.

Then, a message from the agent.

The Panama Canal Authority has just informed us that the time of your scheduled transit has been changed. Due to a shortage of Canal Advisors, your transit is being delayed by one day.

Now not only a Tuesday departure; also the two monohulls, Exit and Swiss Lady were being teamed up with the catamaran – Second Set. We had only briefly met the couple aboard Swiss Lady. We already knew Second Set well. This would definitely simplify things for us. A cat between the two “leaners” would make maneuvering much easier… though Second Set might have other thoughts on the matter. Their job just got much more difficult.

Regarding the one day delay… come on… of course. It’s a boat. Really, there is no such thing as a delay of one day. In the rare event things actually go according to schedule, it should be referred to as ahead of schedule by at least a day.

As it turned out, the delay was a blessing in disguise. What were becoming debilitating knots in our stomachs now had a twenty four hour opportunity to unwind. The last few things we didn’t get around to could now be sorted out the following day. We could actually enjoy a pool day with some relaxing beverages.

We didn’t see Juan at all during the course of the entire day.

Unfortunately, as we felt the knots in our stomachs loosening, Juan was feeling his tighten.

By Tuesday morning, January 18, we were rearing to get moving. Now, any extra time would only make for antsy jitters and unproductive nervousness.

However, during a walk down the dock, Kris spotted Juan in the distance leaning up against a wall, appearing as though he was about to keel over. When we both returned, Juan was emerging from his boat, barely able to stand. He looked to be in excruciating pain.

Clutching his stomach, he said through a grimace he had to get to a hospital. His friend said he needed to go along but he’d be back. One of the marina staff took Juan by the arm and nearly carried him to one of the parked cars.

We felt horrible for Juan. He looked absolutely miserable. He was not going to be doing anything anytime soon. We certainly couldn’t blame Juan’s friend for accompanying him to the hospital. However, we also couldn’t count on his return before noon.

Suddenly, just like that, with less than three hours remaining before we needed to cast off the dock lines and depart the marina in order to follow a tight schedule dictated by the Panama Canal authorities, we were short two line handlers.

Technically, we were only short one. I could fill one of the roles. But one person short was enough to derail everything. To be permitted to transit, each of the three vessels was required to have an outside advisor, full time helms person, and four line handlers. Without those, we would not be allowed to proceed. There was no negotiating.

A quick text message exchange determined that it was too late for our agent to secure any additional line handlers…he said we were shit out of luck.

A frantic trip to the marina office attracted the attention of the marina manager, Juan Jo, who immediately sent out word via Facebook, Messenger, and VHF. He started making phone calls.

Then, projecting all the theatric flourish of a magician performing his final trick, Juan Jo pulled two rabbits out of a Panama hat. With less than two hours remaining until our deadline, on what seemed like a whim, he walked us from his office to the end of D Dock and knocked on the hull of a sailboat tied off to the “T” on the end of the dock. After a short pause, a deck hatch towards the bow lifted and two bleary eyed people poked their heads out.

Jorge, originally from Chile, and Julia, originally from Poland, had just arrived on Jorge’s father’s sailboat from an offshore passage the day before and were still quite disoriented. We had obviously just woken them up.

Juan Jo quickly explained the situation to them in rapid fire Spanish.

Amazingly, they asked for ten minutes to talk it over.

We returned to Exit still dazed and confused. This seemed like a long shot. There was no way they’d want to leap headlong into this with such short notice. Too much going on…

After ten minutes they walked up to Exit.

They had planned to transit the Canal themselves in short order. This would be a great experience. They loved the idea of spending time aboard a Garcia sailboat. They wanted to help out. They could be ready and aboard in one hour.

Huh?

Suddenly, just like that, with the clock ticking down to its final moments, we were back in business.

Kris had painstakingly and brilliantly researched, stocked, and sorted all of the complicated and logistically difficult food requirements for our transit. The morning crisis had all but imploded many of her final food preparations; but, hey… at least we still needed the food. No choice. We’d simply have to roll with it.

There were only minutes remaining before we cast off our lines when learned that Juan was currently in emergency surgery.

His appendix.

Shit.

Had we actually left on schedule the day before, we would have ended up with a potentially life threatening medical emergency aboard Exit while on Gatun Lake mid-transit through the Panama Canal. An emergency evacuation would have been an absolute nightmare. The whole situation unfolding in that semi-remote location overnight would have been unimaginably fucked up and stressful.

Shit.

Most of the time I find Murphy’s Law reigns supreme. This was one of those instances when things really seemed to happen for a reason.

Call it luck or fate… sometimes you simply have to smile when it goes your way.

In this instance, the Canal Authority’s scheduling delay was the best thing that could have happened to us. Knowing a bad situation could have been far worse, all we could do now was hope Juan’s surgery went well.

Shortly past noon, with five people standing on deck in addition to the two marina staff standing on the dock, Exit backed out of the slip, reversing her direction one hundred eighty degrees in a spring line maneuver that we had performed flawlessly six months prior with only one person on deck and two on the dock.

This time… we can only hope the clusterfuck that ensued was not caught on video. We eventually ended up in the right direction where we needed to be; but by no means was it textbook, or even slightly pretty. With five more knots of wind, it could have been a catastrophic disaster.

Yikes. A bit of an embarrassing start. Unforced errors would not bode well inside the Canal.

Moments later we had set our anchor just outside Shelter Bay Marina in an area known as The Flats. Shortly after that, a pilot boat raced toward us, carrying our advisor. With brutally intimidating aggression and flawless precision, the pilot boat captain roared in, briefly stopped less than a foot from our boat in quite choppy seas, allowing the advisor to deftly step from the bow of the pilot boat onto our deck, then backed quickly away, before I could fully process how disastrous, that too, could have been with less skilled people.

We currently had more people on Exit than had ever been since we first climbed aboard. The official Panama Canal Authority advisor, Victor (a required presence responsible only for giving advice – not piloting the vessel); the two line handlers provided by the agent, Mario and Jamir; the two volunteers who had saved our asses, Jorge and Julia; as well as Kris and myself.

Our initial task was getting under the Atlantic Bridge as expeditiously as possible so all three boats could rendezvous just before the first set of locks. The clouds above threatened to unleash a deluge which would have made keeping seven people dry an impossible task. Thankfully, the threats never amounted to more than a few brief sprinkles.

At this point we were only an hour into the adventure and already we would have to accomplish what would seem to us to be the most complicated, stressful, and risky undertaking of the entire transit. It was the task we, on one hand, had the most control over and yet, at the same time, relied the most on everyone aboard all three boats to coordinate as an overall effort without fucking anything up. If there was an issue, it would not be because of a cargo ship or a lock worker.

While still freely adrift in the channel, all three boats had to raft up together, securely enough to be able to move as a single unit into and out of each of the locks.

With a bit of discussion and practice, it seemed possible to coordinate the procedures, communications, and assignments necessary to try to attempt this without a high risk of causing damage or injury to any of the three vessels or twenty one people involved.

Except… there would be no practicing and very little discussion:

Second Set would approach Exit which would be facing into the wind idling in neutral. Helm commands for all boats would be issued by the cat’s advisor and relayed through the other vessels’ respective advisors. With Second Set alongside Exit, fenders in place, bow and stern lines secure, and spring lines run and secured – Swiss Lady would approach the two rafted boats and repeat the process. Once the boats were nested together, primary control of navigation would be the catamaran’s responsibility with the other boats providing supplemental propeller thrust.

Oh, ya… and we’ll also have to take into account the one to two knots of surface current… and the fifteen knots of wind… and don’t forget to keep an eye out for any other potential boat traffic.

Piece of cake.

The advisors knew exactly what was going on. They did this for a living. Half the line handlers knew exactly what was going on. They did this for a living. For everyone else, it was imperative to pay attention and not screw anything up. A mistake could result not only in a very expensive collision, but also potentially an amputation or drowning.

To everyone’s credit, the entire process went remarkably smoothly. In particular, the individual advisors and helms people did an amazing job of executing an extremely difficult series of maneuvers in far less than perfect conditions. Hats off to Kris on that one.

Personally, I felt the number of moments of sheer terror were kept to a very reasonable minimum. Well done.

With both monohulls nested securely on either side of the catamaran, the now unwieldy flotilla resumed its course, carefully maneuvering toward the first set of locks.

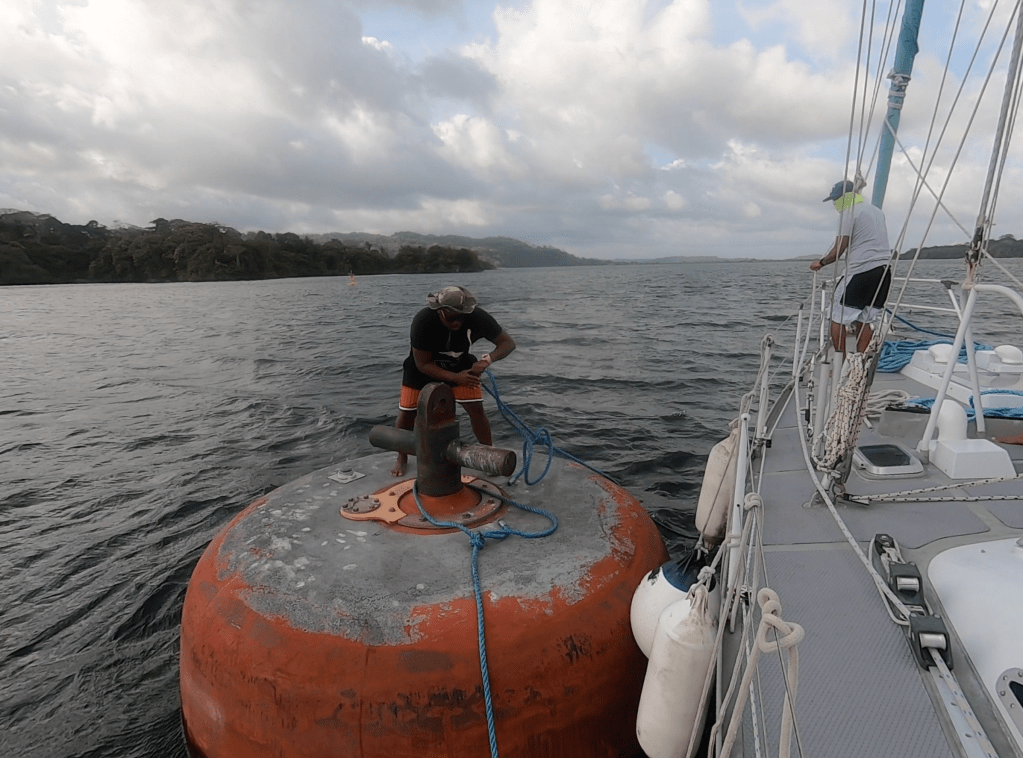

Entering Gatun Locks, line handlers on both sides of the cement walls throw lines weighted on the end with heavy knots called monkey fists to the boats.

With a fore and aft line on either side of the lock, four in all, the lock line handlers begin walking the rafted boats into the lock chamber.

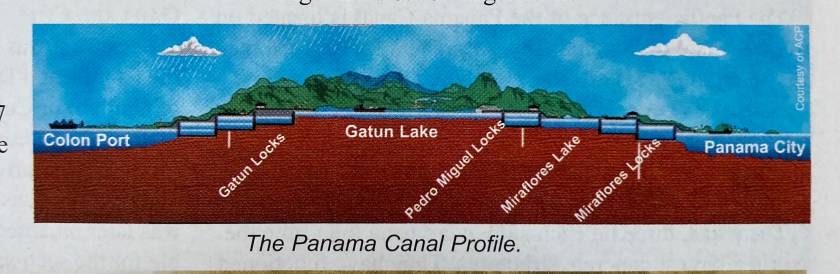

As we approach the first of three chambers that make up Gatun Locks, the unforgiving-looking cement walls on either side begin to tower upward. Railroad tracks can be seen running parallel along the wall that carry the small rail cars which cable themselves to the large cargo ships and actually tow them into the lock chambers.

Directly in front of us, at first looking deceptively small only because of the sheer size of the canal lock surrounding it, quietly awaits “Ensemble”. In actuality, it is a massive six hundred foot long chemical/oil tanker ship that will be sharing the lock with us, sitting just in front of us.

Behind the prop of a cargo ship is not a comfortable place to be, period. Ever.

Less than an hour ago, as we were approaching the Atlantic Bridge, Jorge had asked our advisor about the horror story I had been told in the marina.

To our dismay, Victor confirmed that the story was actually true!

Not only that; he went on to reveal that, in fact, he was the very advisor aboard the catamaran that day.

It was a shit show, according to the man that was there. However, Victor also pointed out two important contributing factors were 1) the monohull rafted up to the cat was in horrible condition and 2) the cargo ship in front had just changed pilots, and the new pilot had been given an incomplete update which failed to include any information regarding other vessels sharing the lock chamber.

Disconcerting when you are now sitting behind a cargo ship in the lock. You hope the pilot in front of you has been well briefed.

Surreal is an understatement.

As we enter the first chamber of Gatun Locks, the line handlers standing on the lock walls cast light lines meant to be attached to the heavier lines we have aboard which are then pulled back across the water. The line handlers on the walls “walk” the rafted boats through the chamber and secure the lines to huge bollards along the lock walls once the boats are in place. Heavy knots known as monkey fists give the light lines enough weight to be thrown the distance. You do not want to be hit by one of these. In fact, we were warned in advance to cover solar panels and hatches accordingly.

Some stories had gone so far as to imply instances in which lock workers throwing lines actually appeared to make an effort to target solar panels. This seemed far fetched, though still a bit unsettling.

The giant lock gates can be seen, flush against the lock walls where they rest while in open position.

Tracks for a small railcar system that helps guide, tow, and physically control the big ships via steel cables can be seen running alongside the lock walls. Our raft of boats, by comparison, had to carefully maneuver itself from chamber to chamber.

With the three rafted sailboats finally in place directly behind the behemoth tanker ship towering menacingly above our bows, and all the lines properly secured, the medieval looking gates behind us slowly start closing. Despite the fact that they are enormous in scale, meant to withstand the force of millions of gallons of water, they move deceptively smoothly and in absolute silence. Without watching them, it is hard to notice they are even moving.

With an exquisite delicacy of mechanical balance, the two massive gates pivot inwards, silently arcing towards each other in a perfectly mirrored symmetry. The gap between them grows smaller and smaller at an almost imperceivable rate. Finally, the last sliver of light separating the two gates disappears as they close completely.

Nearly as subtle as the gate movement, the level of water in the lock begins to rise.

It can’t be felt.. only seen as the waterline creeps vertically up the walls of the lock chamber.

Perhaps one of the biggest surprises of all was exactly how quiet the entire process was. No massive noises from the ship in front of us. No massive noises from the lock itself. I expected the industrial din of a port and heard almost nothing.

Also surprising was the lack of any sense of motion inside the locks with the water exchange. Crazy whirlpools or washing machine effects from the ridiculous amount of water entering the lock never materialized. Turbulent eddies and roiling, churning currents caused by wash from the colossal prop on the ship in front of us never happened. It felt more like a filling bathtub without the turbulence from a faucet.

One of the critical jobs of the line handlers aboard the boats as the lock fills with water is to take up slack in the lines as the distance changes between the boat cleats below and the lock bollards above. A stray line caught in a prop is a really, really bad thing to have happen here.

Monitoring the line tension becomes even more critical at the other side when the water levels in the locks are lowering the boats. An unmonitored line can tension up quickly, resulting in the entire boat’s weight hanging on it, leaving no option but to cut the line, causing potential catastrophic damage and/or injury.

The lock workers were solid. Our line handlers were solid.

It all went like clockwork.

Slowly we moved through Gatun Locks.

We repeated portions of the process two additional times as the three locks raised us us a total of eighty four feet.

As the third chamber finished filling, we received a fist pump of support from one of the many anonymous lock workers who helped us that day. Any previous held trepidations regarding potential ill intentions of lock workers who might feel motivated to damage our solar panels or hatches dried up completely and blew away.

Nearly twenty five million gallons of freshwater had passed under us to complete the task of raising us to the elevation of Gatun Lake. A somewhat sobering thought to realize that volume equates to more fresh water than everyone currently inside the lock combined will drink in a lifetime.

The final gate of Gatun Lock opens and the oil tanker in front of us quietly begins to pull forward. The disturbance on the water’s surface from the immense ship’s prop wash is noticeable, but only barely… the pilot obviously has received a thorough briefing and for that we are grateful.

As the outline of Ensemble shrinks into the distance, we are left with an open channel leading into Gatun lake.

Once clear of the locks, all of the lines are released and the floating raft splits apart, separating back into three individual sailboats.

It’s now only a short run in Lake Gatun to reach the mooring buoy we will spend the night on.

A big ball, to be sure.

Still, given the option, I’d prefer to keep my balls to myself.

Though the line handlers were all spending the night aboard, the advisors were immediately picked up by a pilot boat. We would see them again at first light. We hoped Victor would be reassigned to us…

Getting to this point had been no small feat.

That was not lost on us.

Currently, the only unresolved issue of the day seemed to be whether or not we were going to have ice cold beers, even though we had completed only half of our Panama Canal transit. For some reason, this had been in question.

However, with the unmistakable phssst sound of an opening can, that question was definitively answered.

Now we just had to get through tomorrow.