September 21 – November 6, 2024

Six weeks simply wasn’t going to be enough time.

Excluding our previous stop at American Samoa, which had been a weather diversion, it had been over five years since we had spent so little time in a country we had sailed to. And yet, only two weeks after arriving in Tonga, it was already into November with cyclone season technically underway.

Nine months earlier, while still in the Sea of Cortez, after reading something online Kris had stated flatly, “I want to swim with whales in Tonga on my birthday.”

As it turned out, by October 26 this year the whales had already left Tonga, beckoned south towards Antarctica by an early cooling of the surrounding waters. It was our good fortune that, by that time, we had already sailed over six thousand nautical miles across the Pacific Ocean, arrived in Tonga, and dived with whales just three weeks earlier, not once, but twice.

Not quite perfect timing…but close. We couldn’t hold it against the whales.

It was late in the season. Still we had made it.

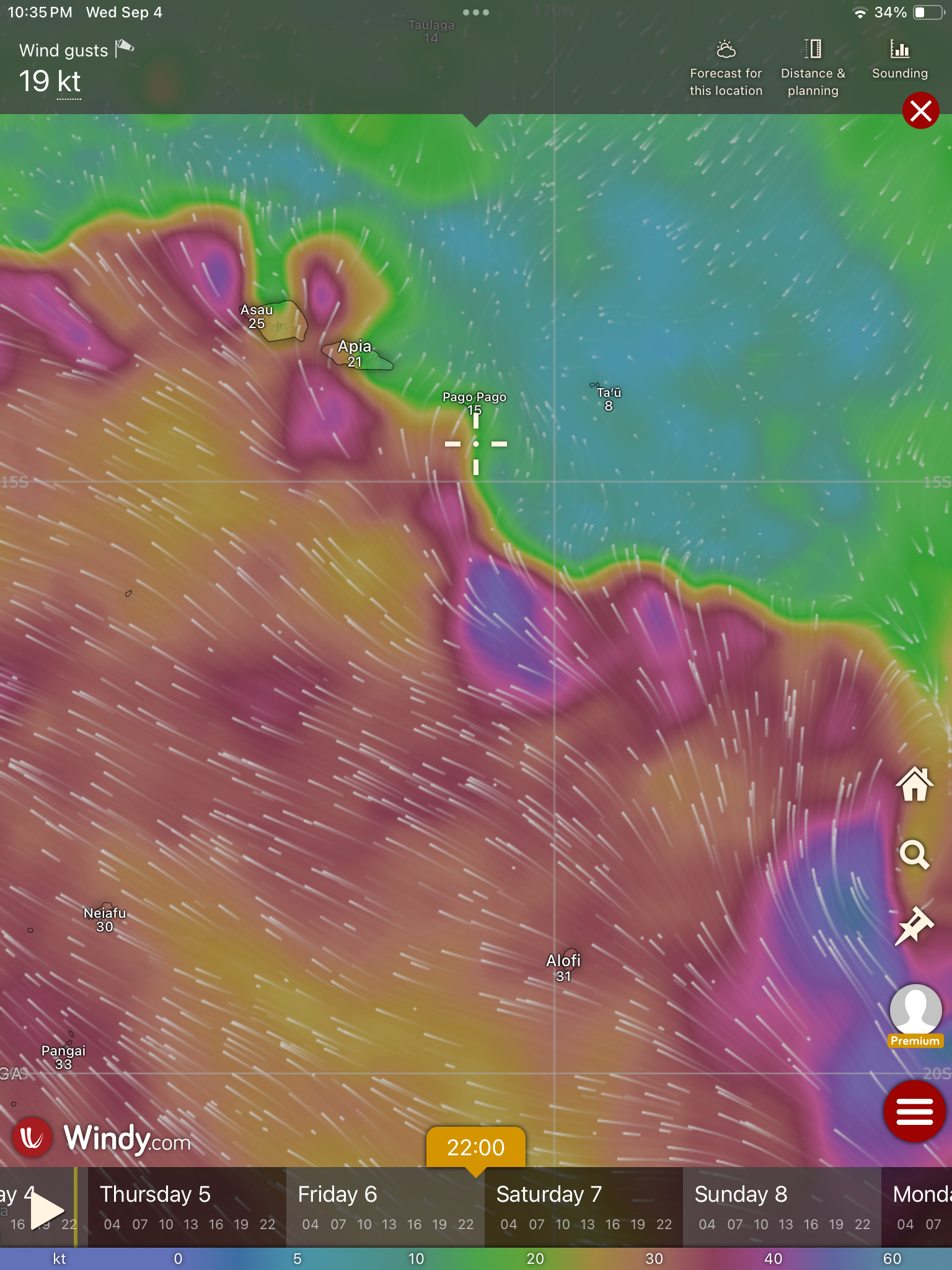

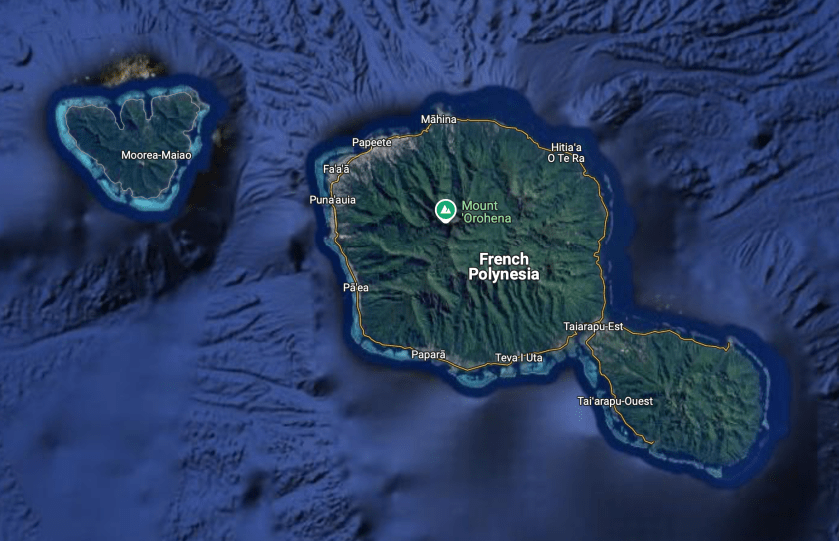

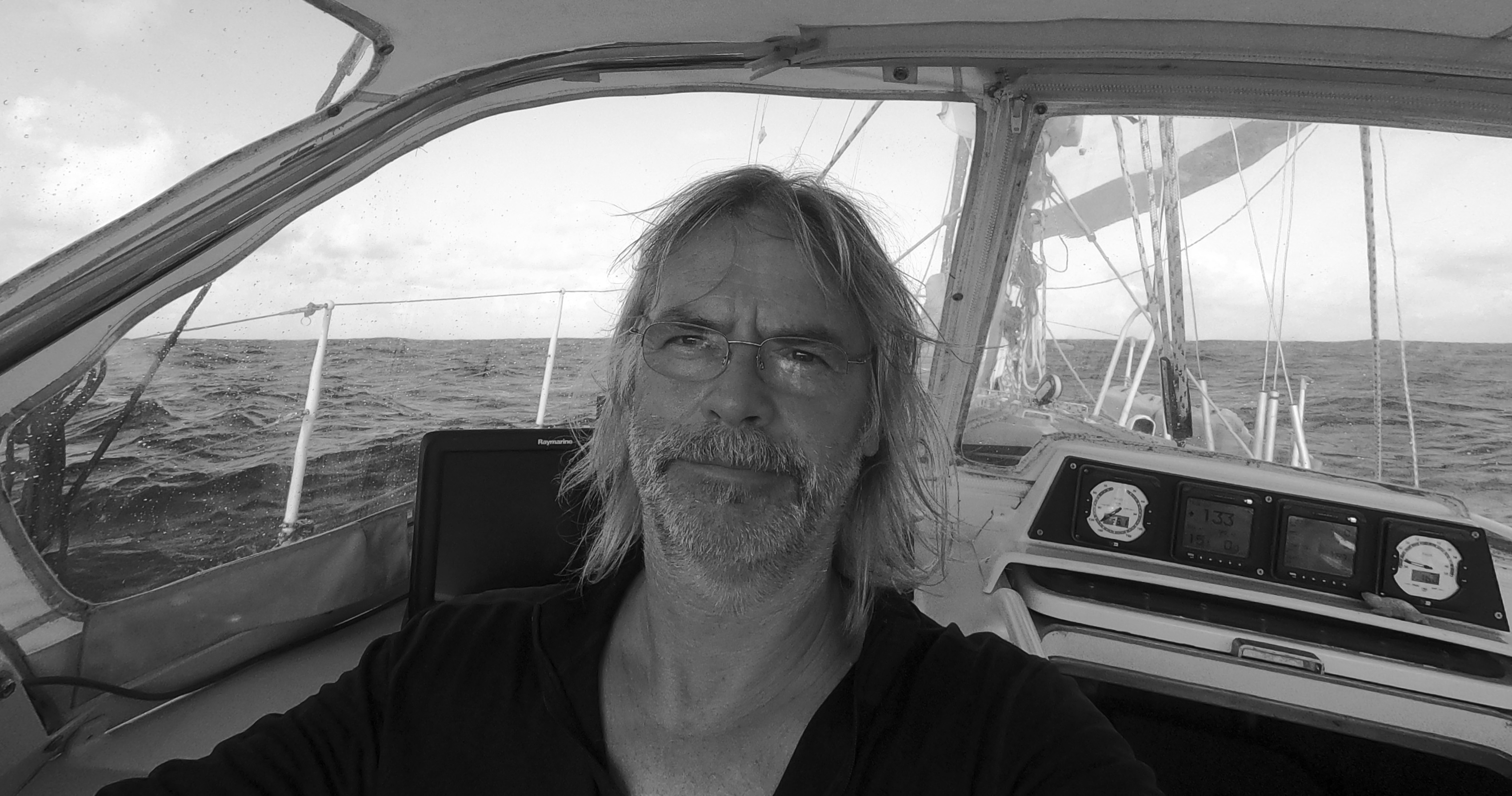

To be sure, getting to Tonga from French Polynesia had been an epic, at times harrowing, and certainly exciting journey. We had experienced both some of the most thrilling and nerve-wracking moments in the entirety of our sailing experiences.

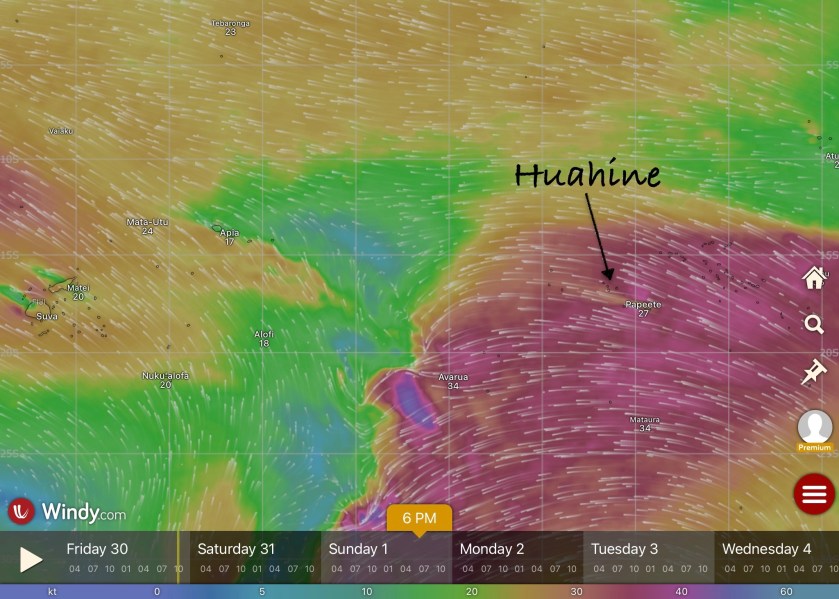

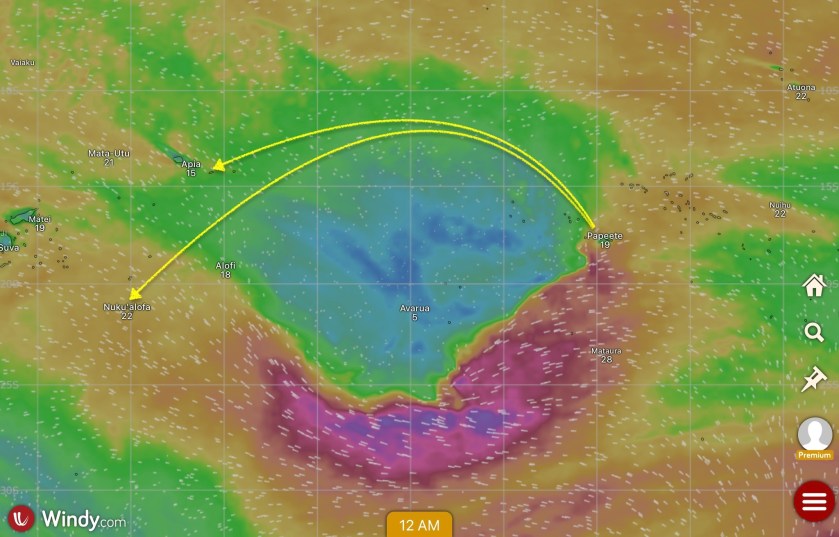

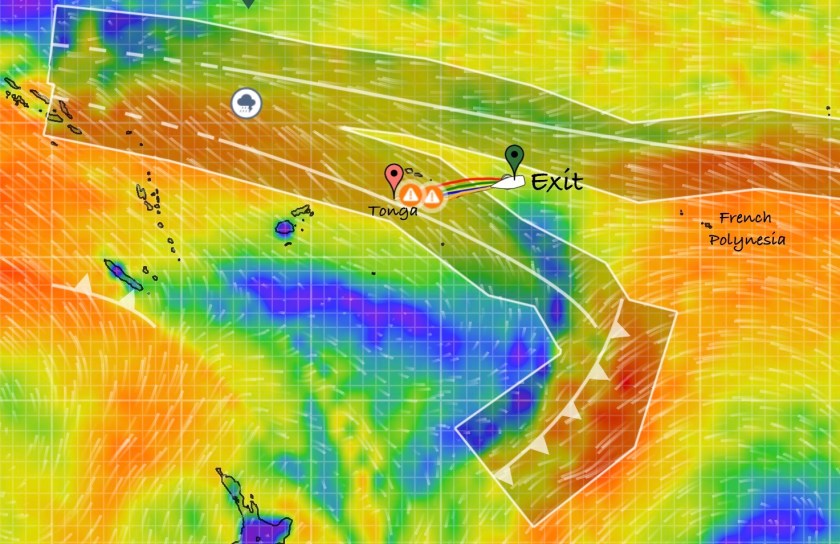

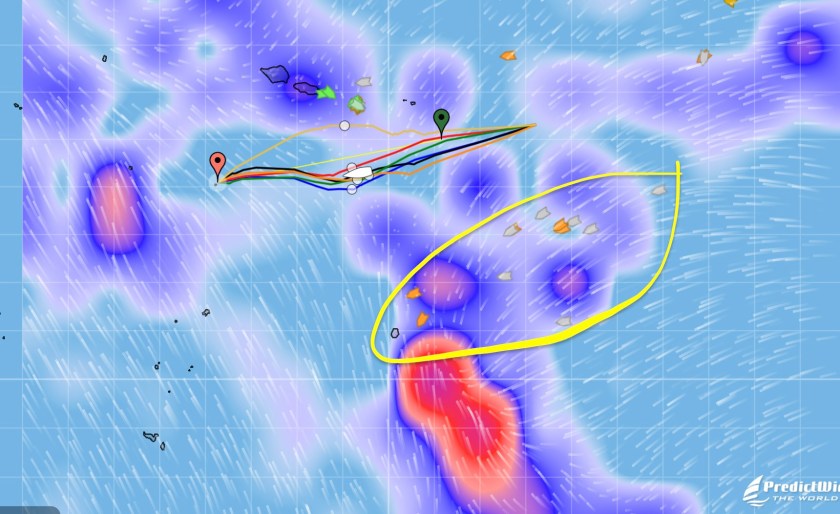

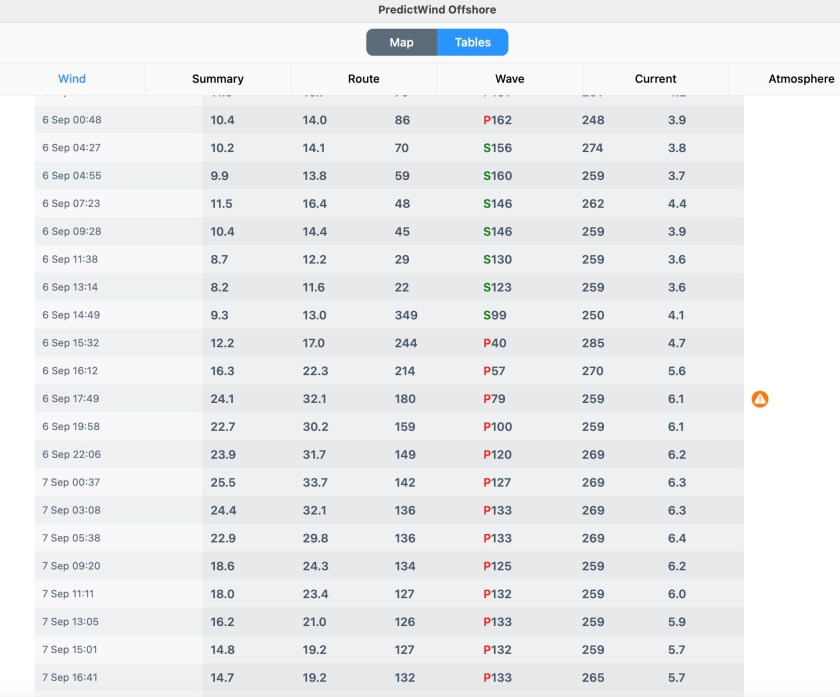

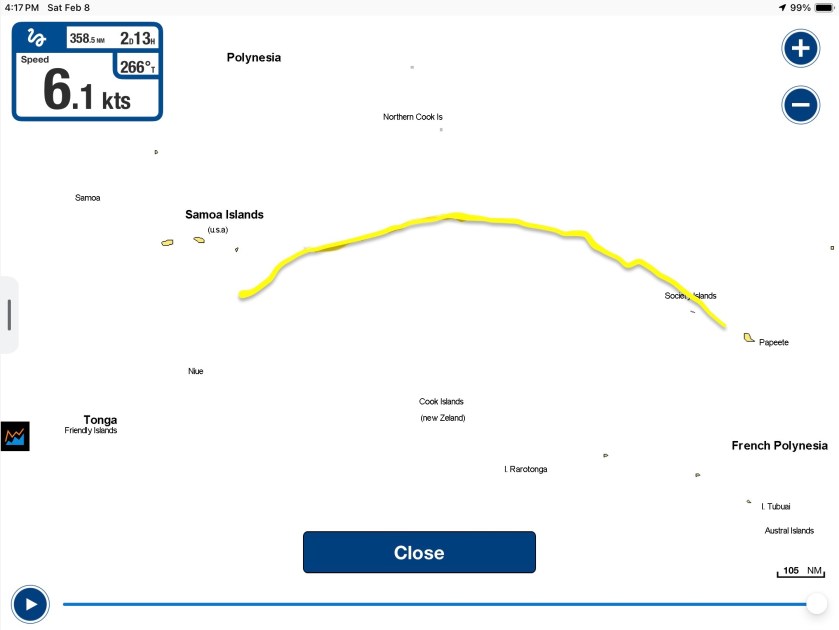

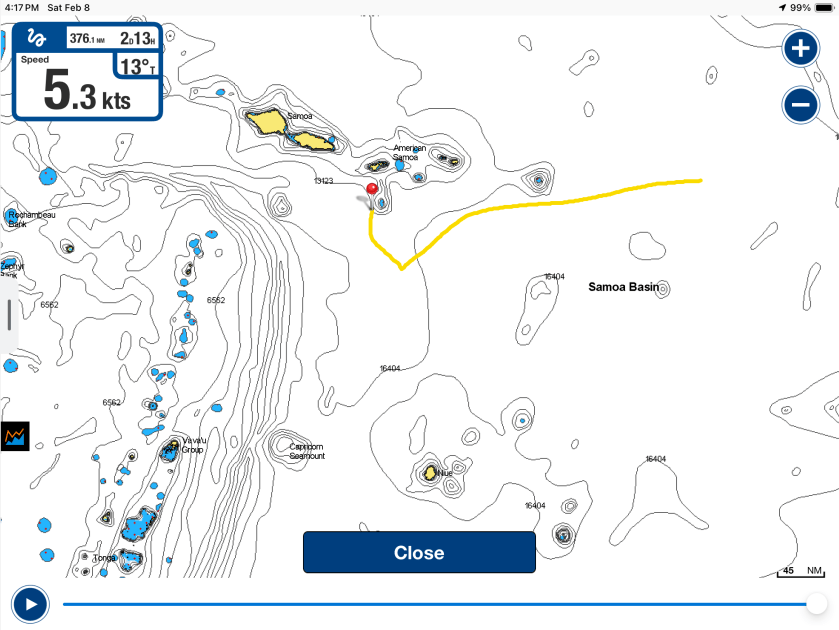

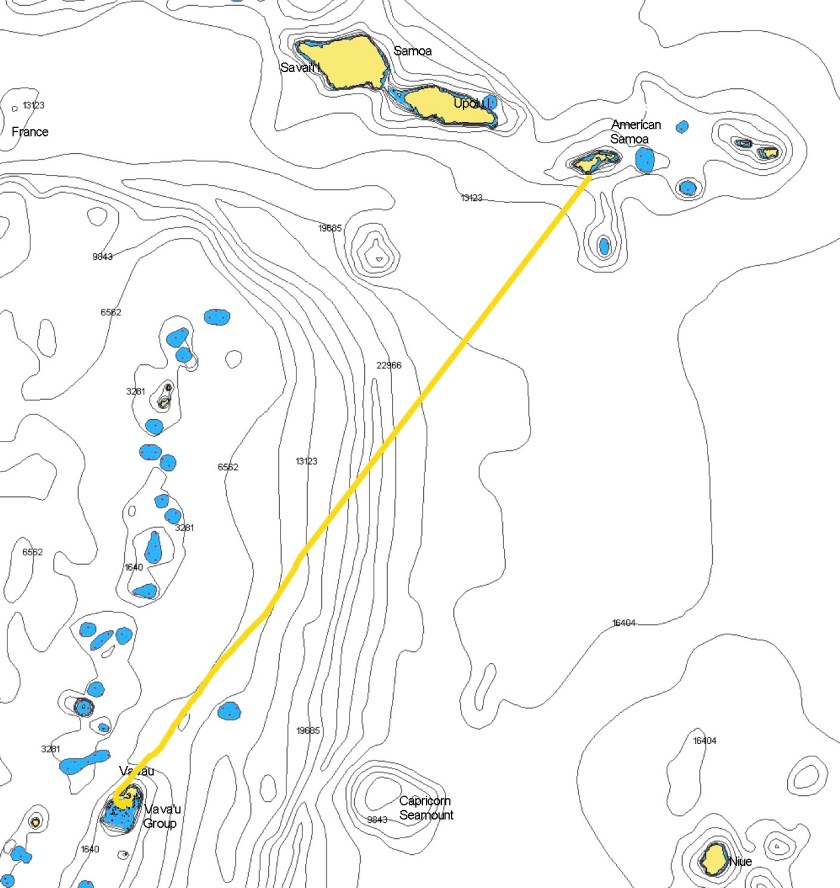

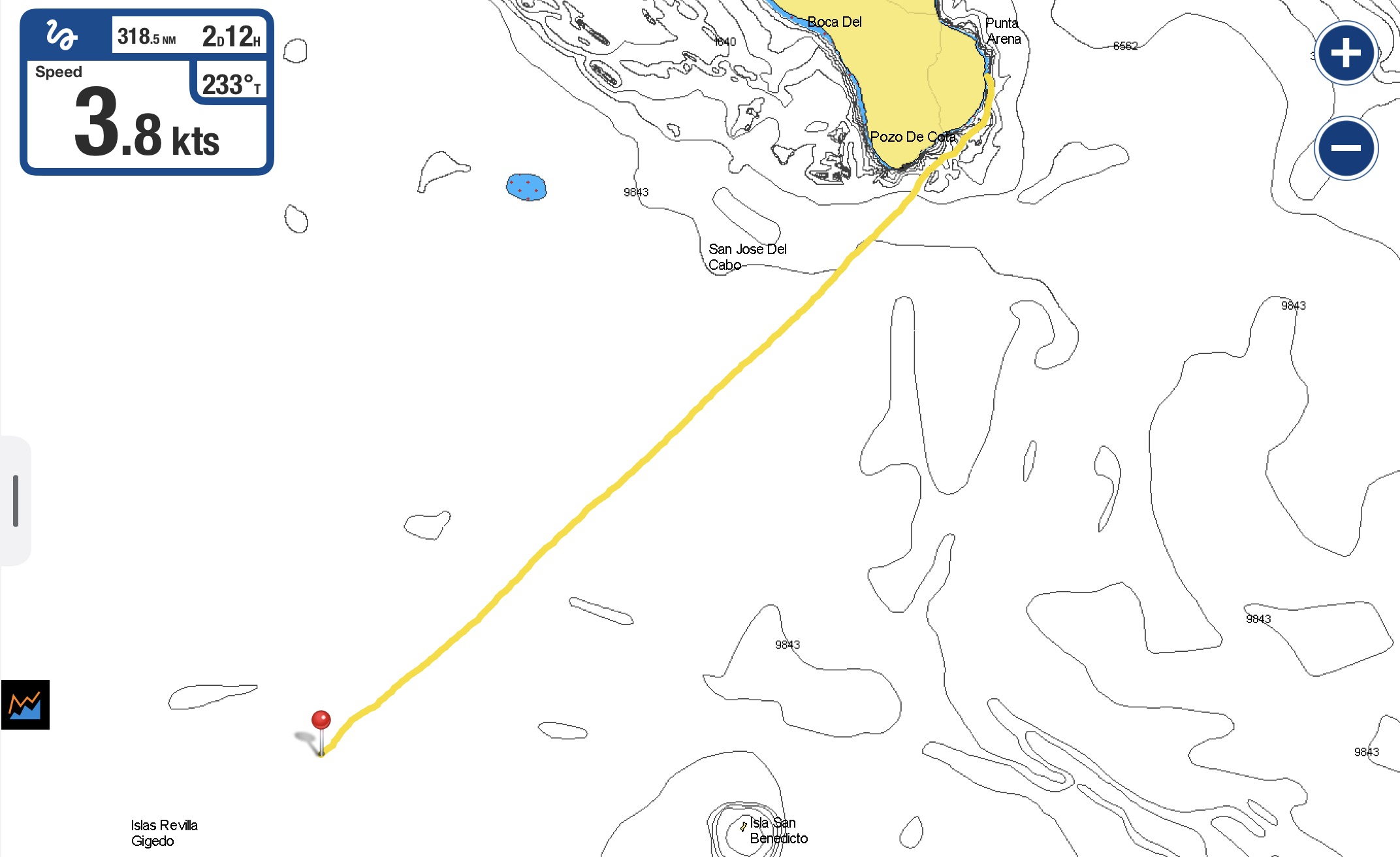

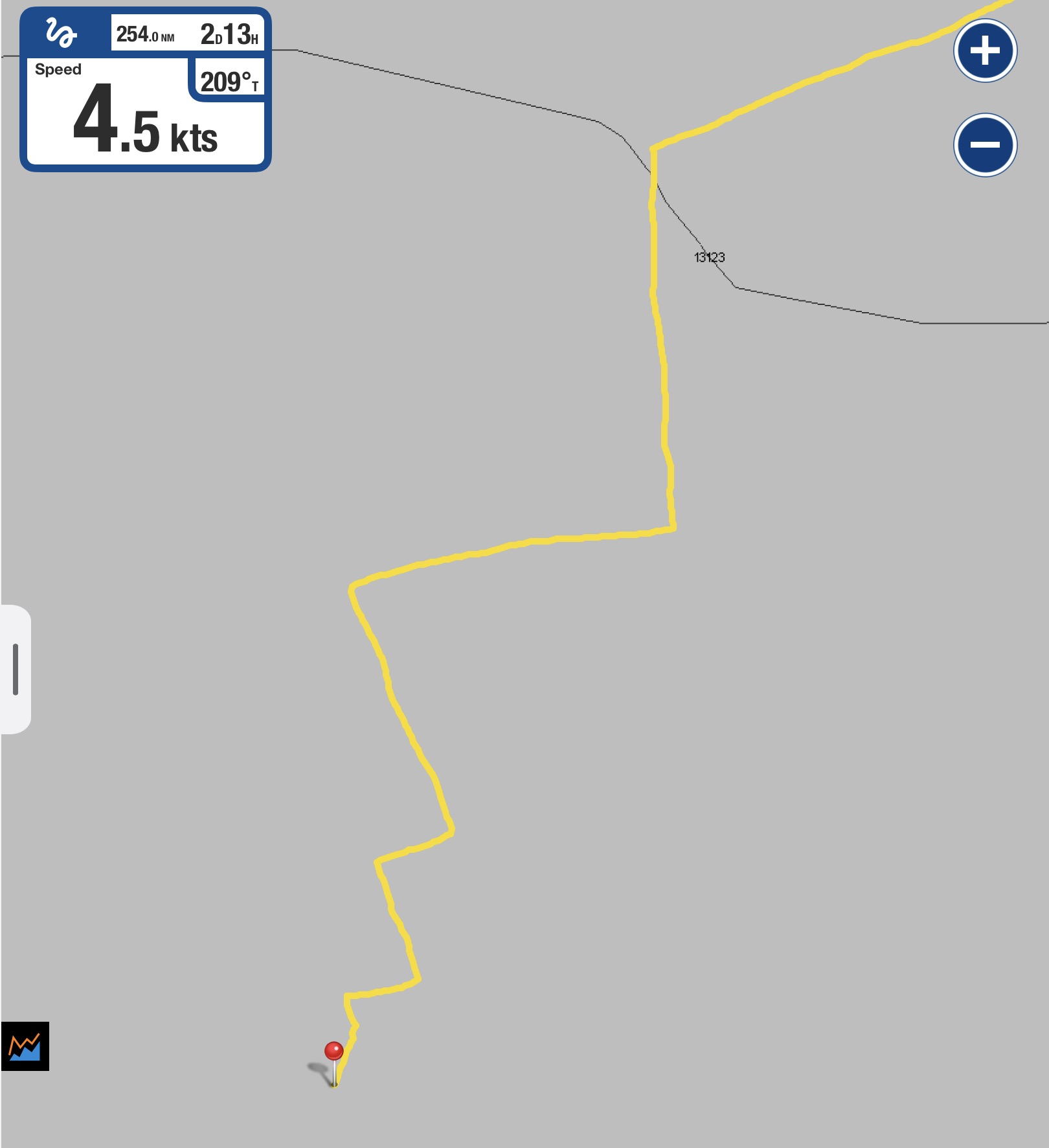

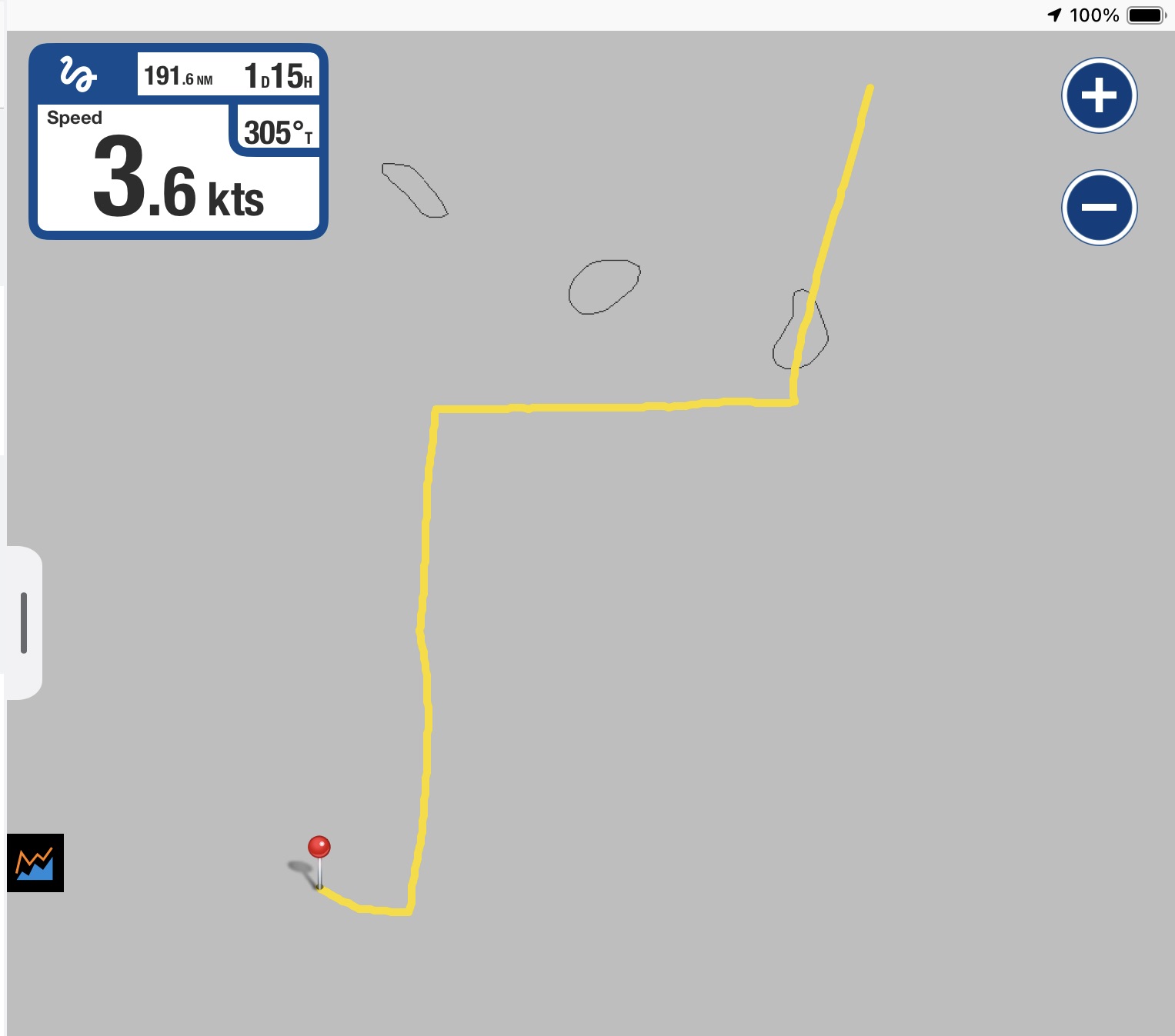

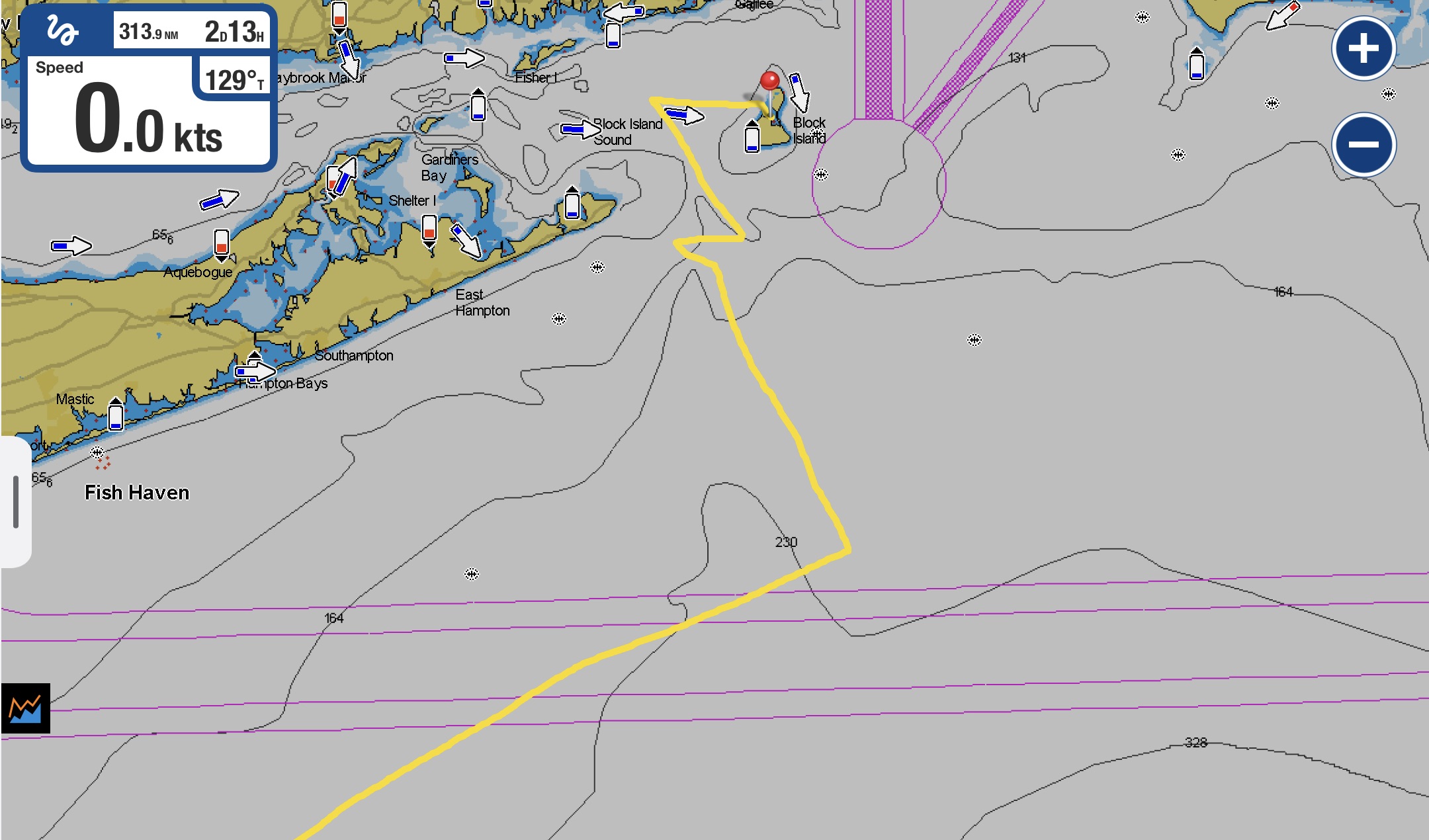

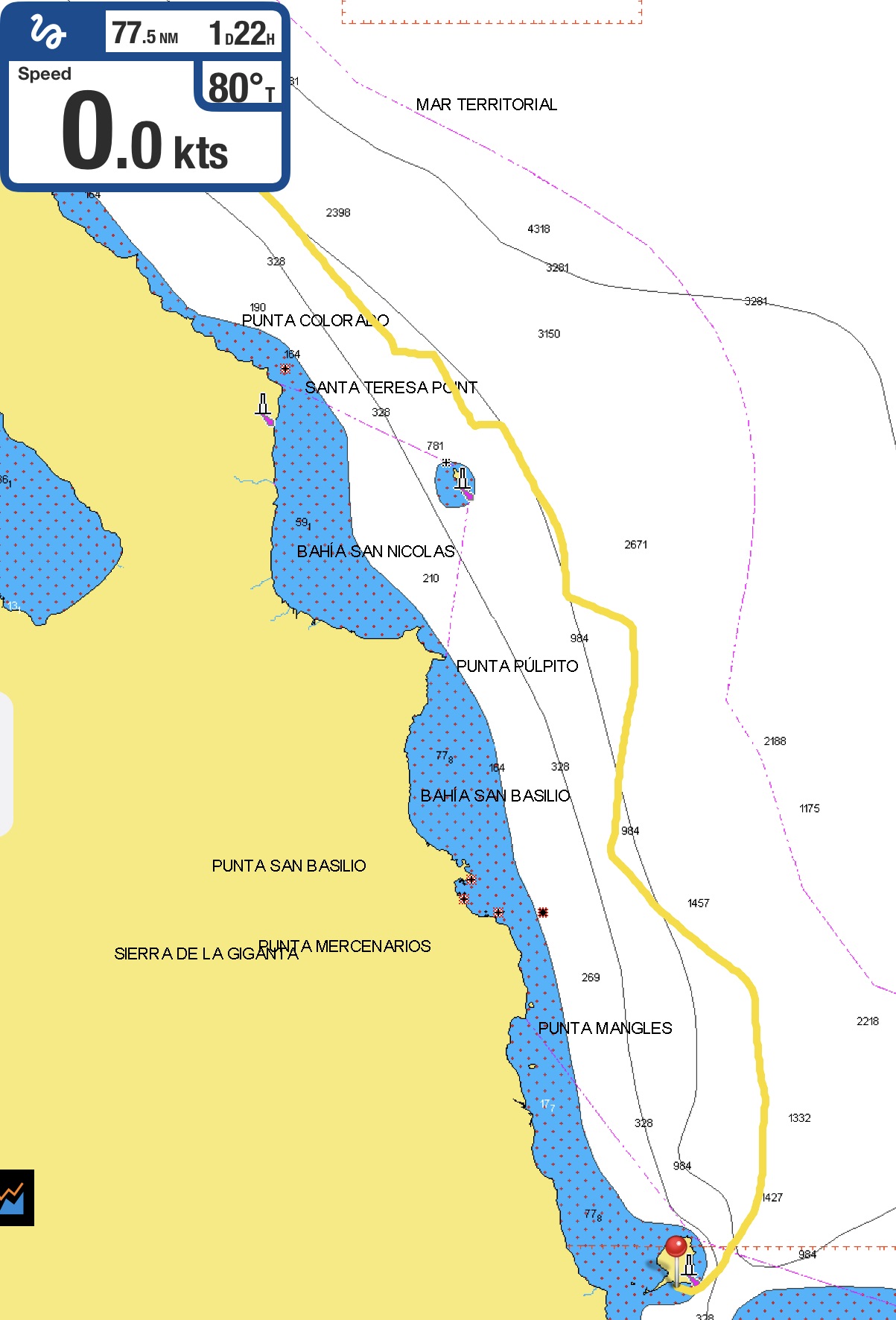

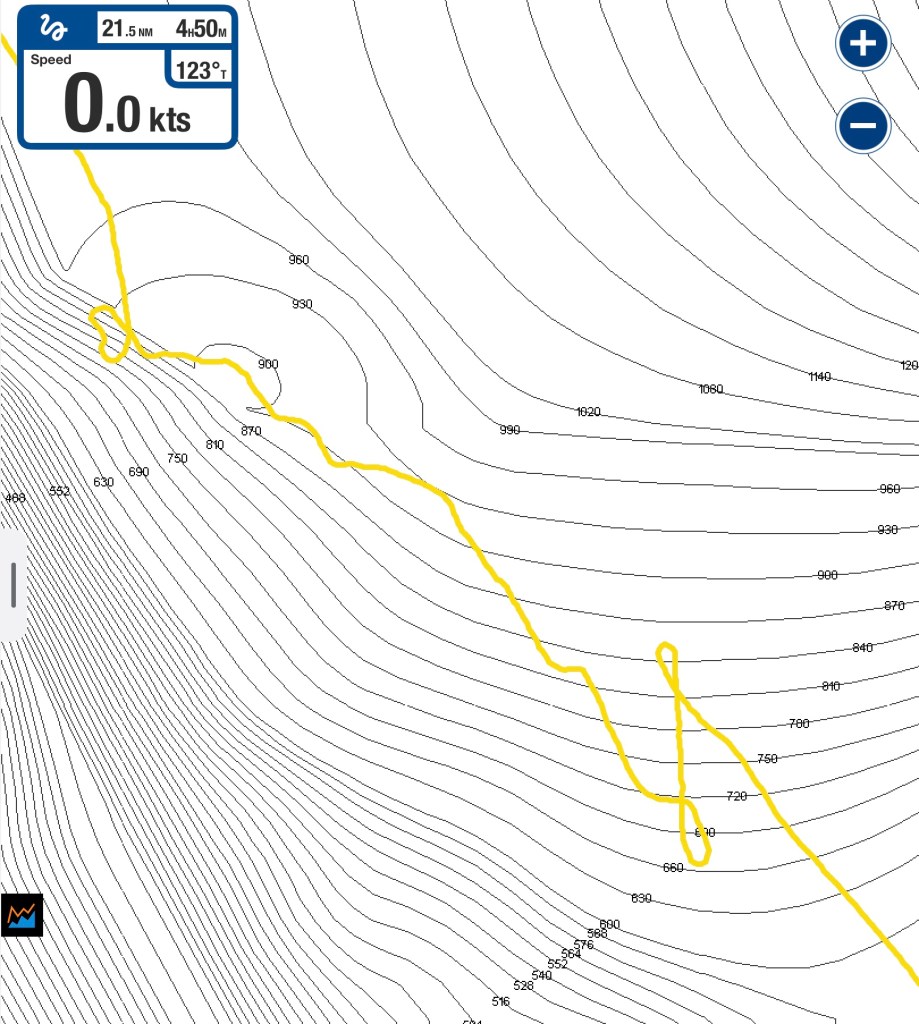

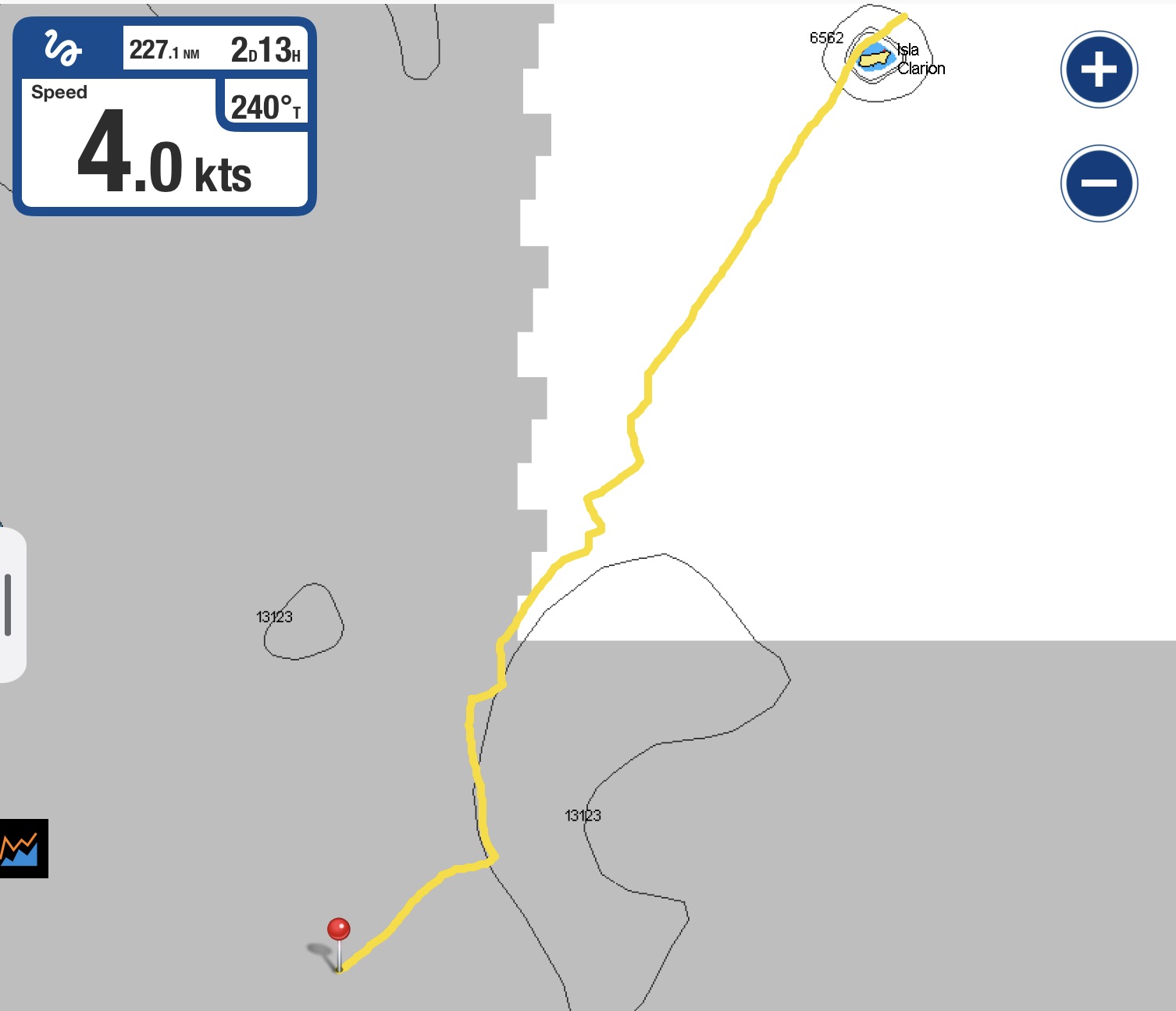

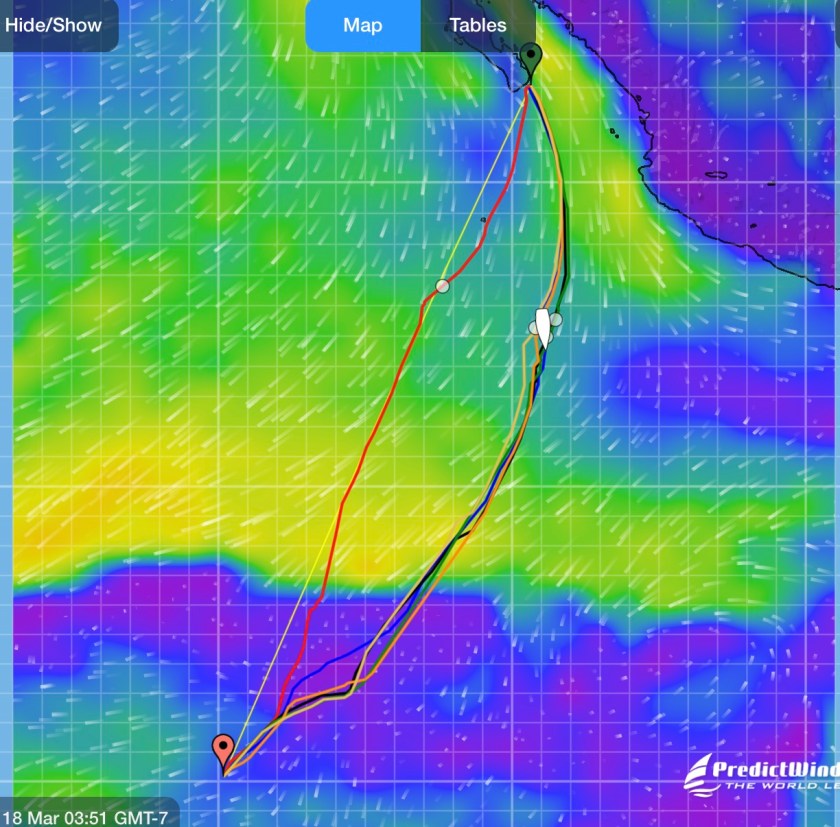

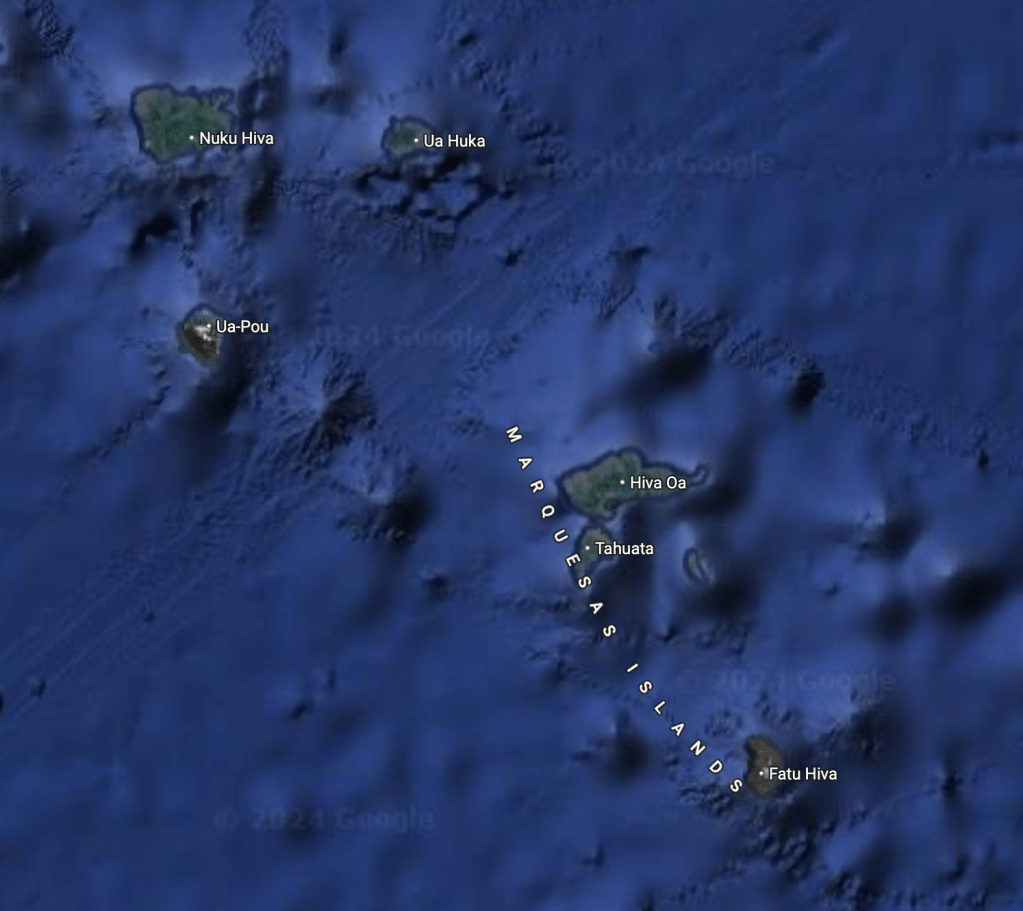

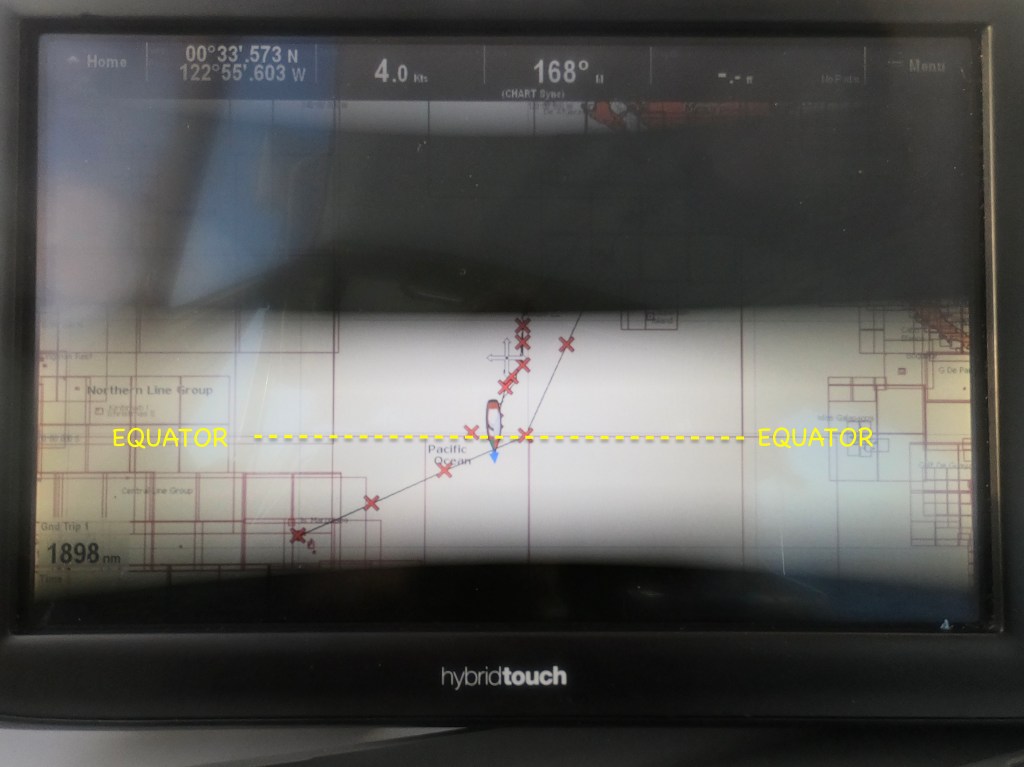

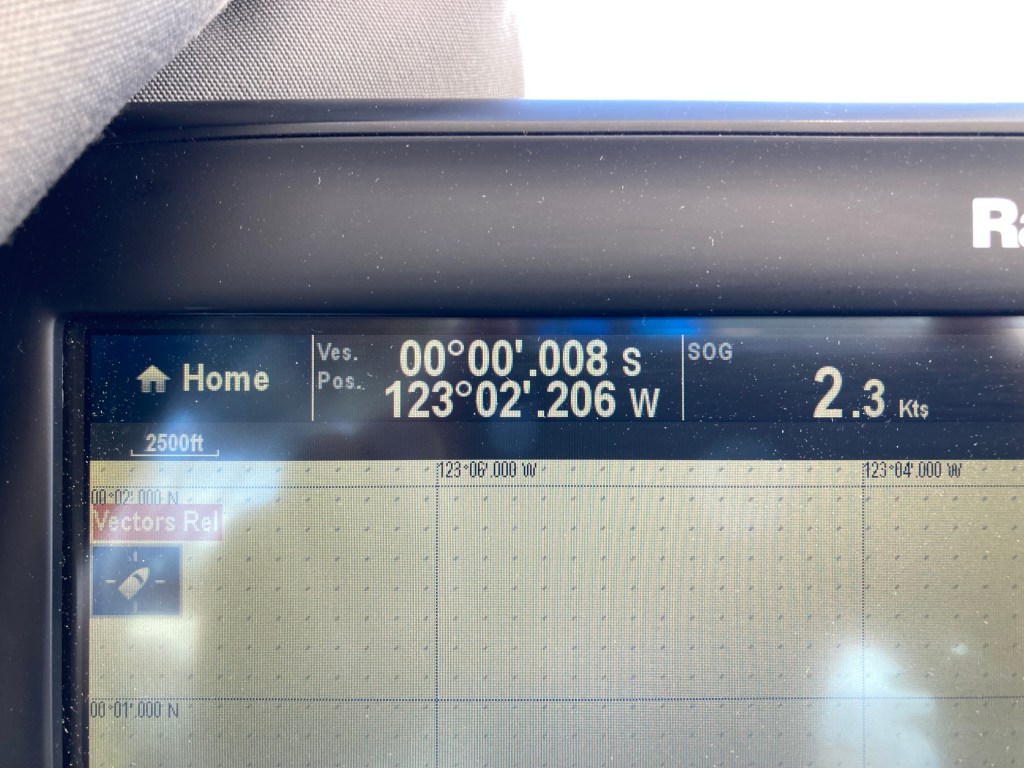

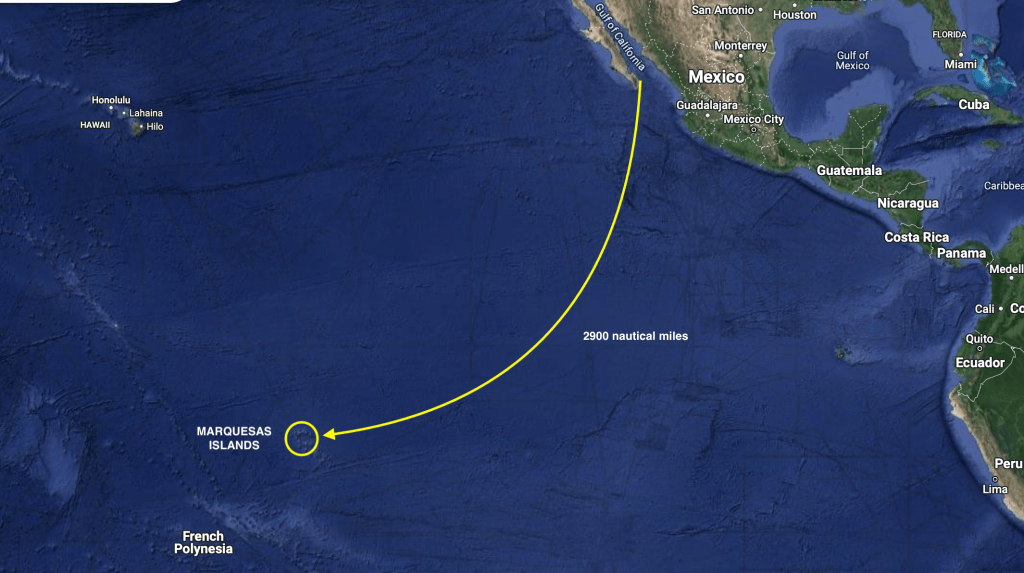

The massive arc from French Polynesia to American Samoa, though nothing close to our 3000+ mile passage that initially got us to French Polynesia from Mexico, still represented only the second time we had ever travelled more than one thousand nautical miles in one go. And, though the American Samoa to Tonga leg was not nearly as dramatic as the Mexico to French Polynesia passage had been, it remained no small feat.

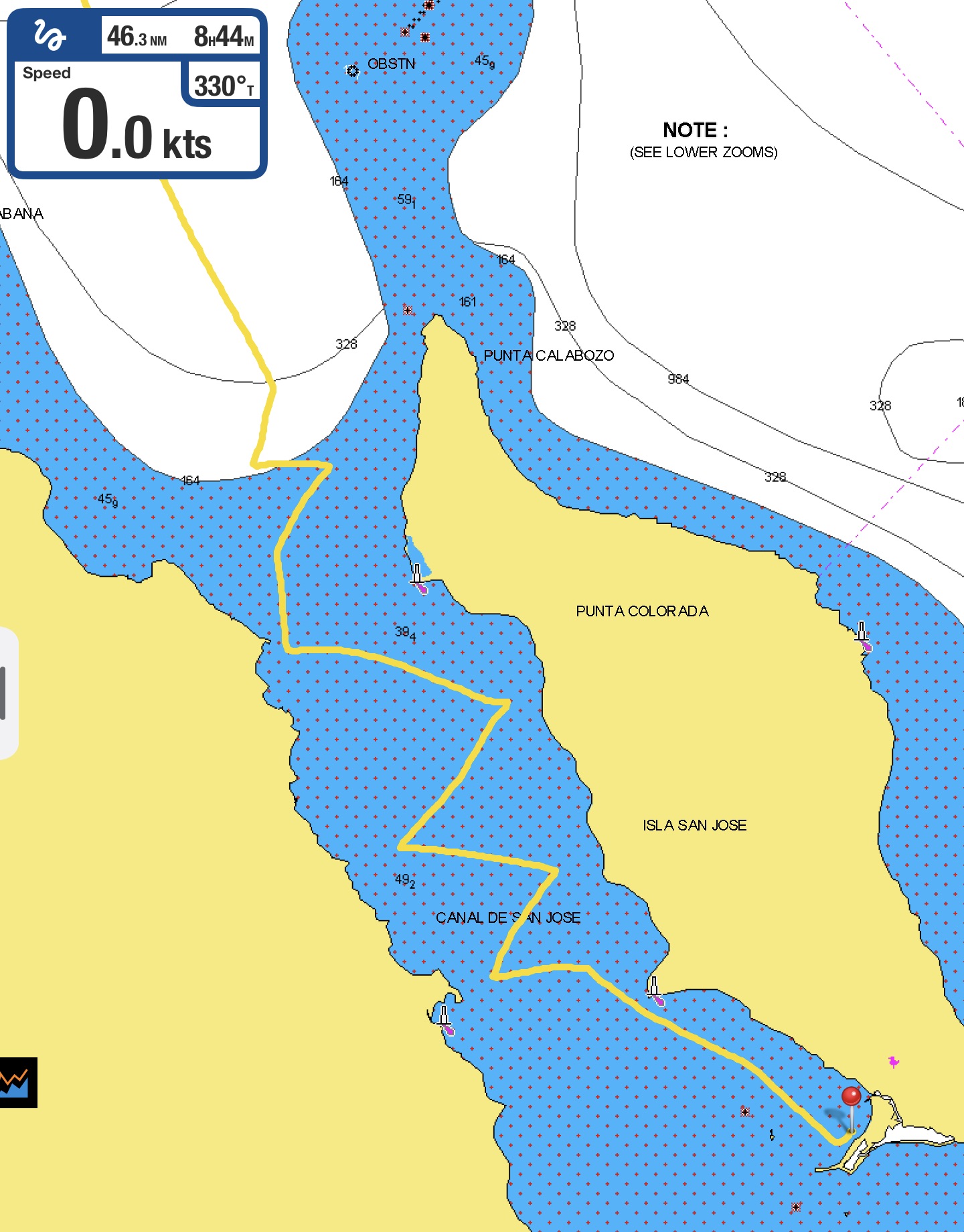

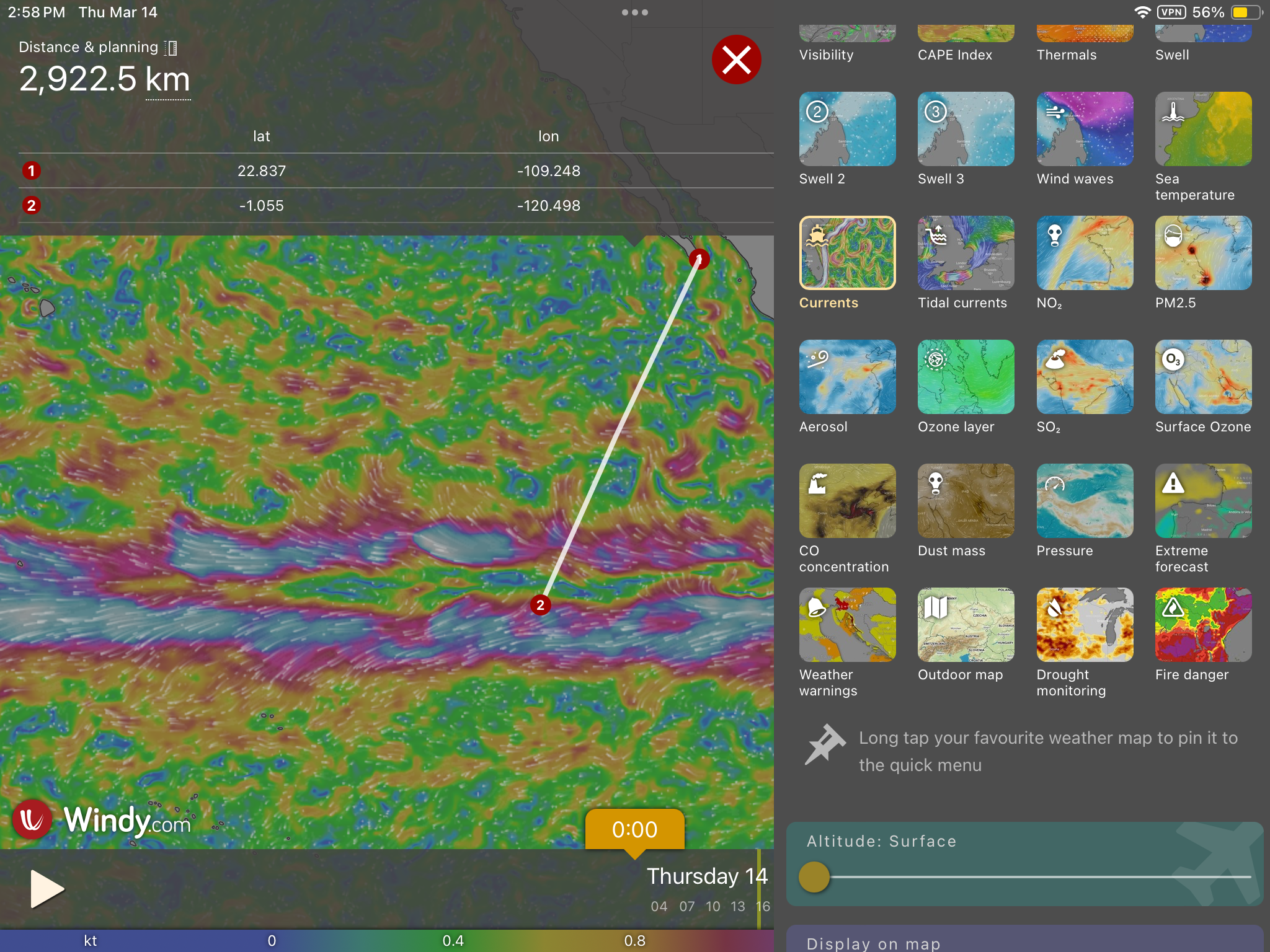

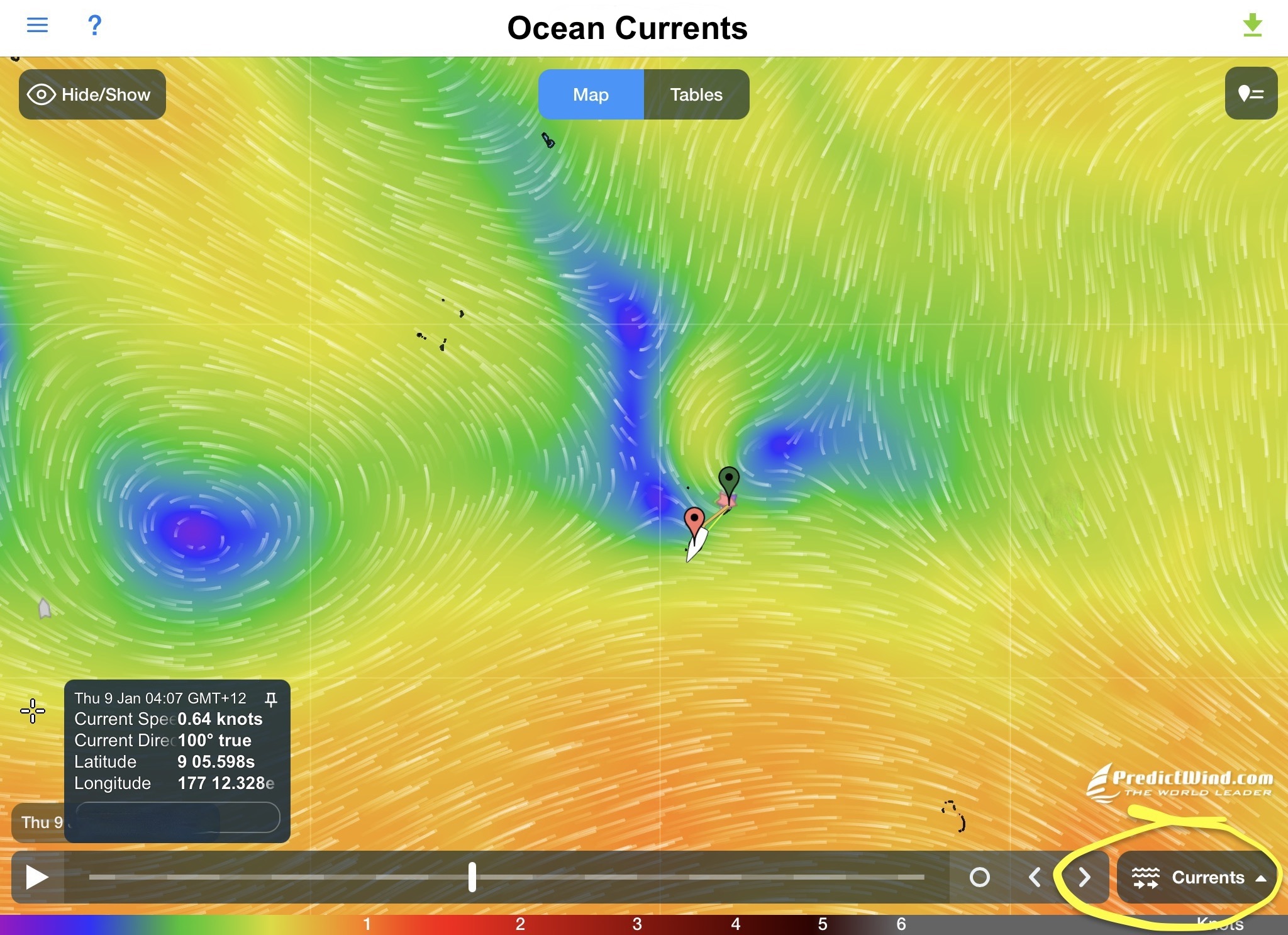

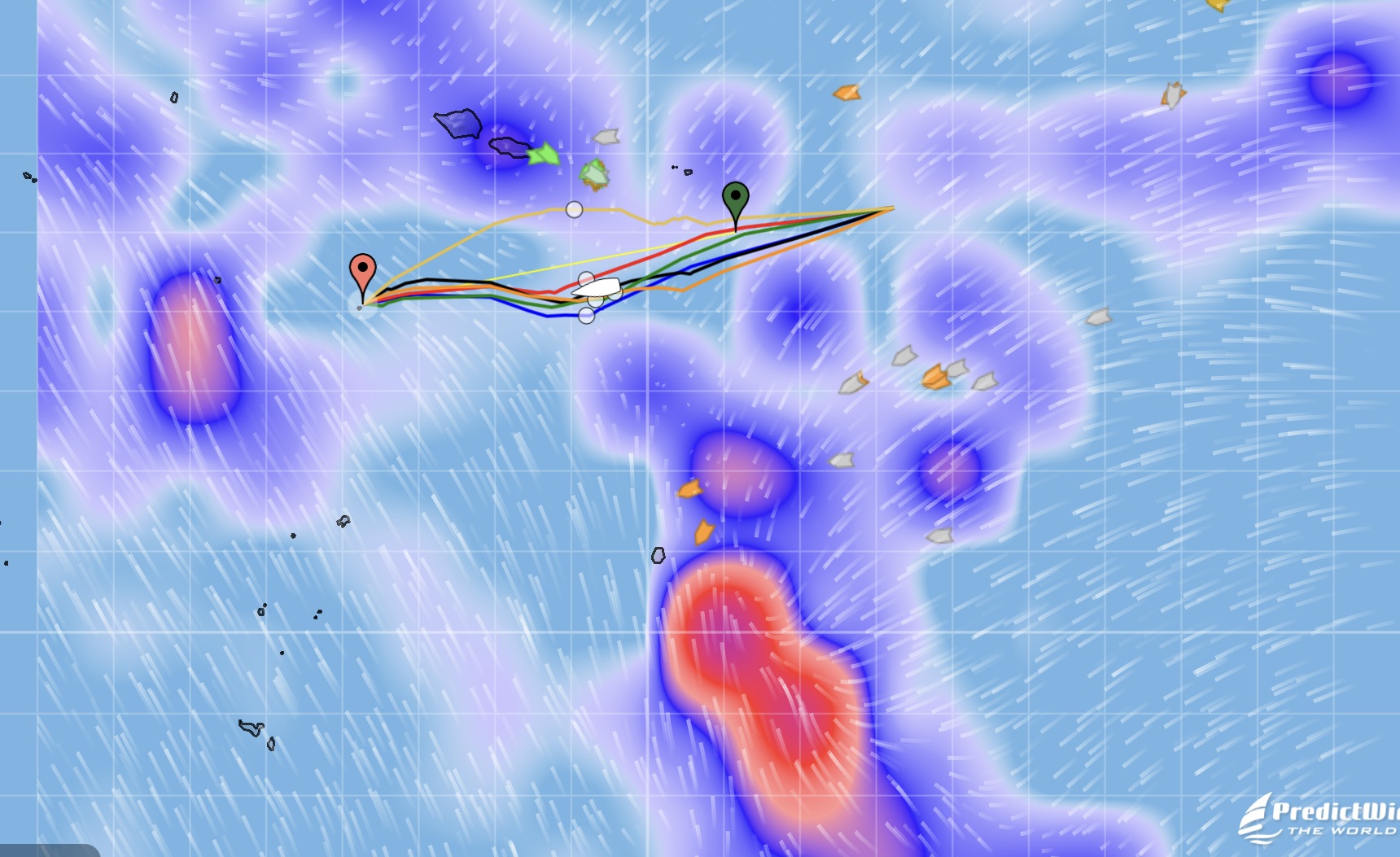

One thousand three hundred sixty six nautical miles from French Polynesia to American Samoa in just over ten and a half days. Followed by another three hundred fifty seven miles to the Kingdom of Tonga in just over two and a half additional days.

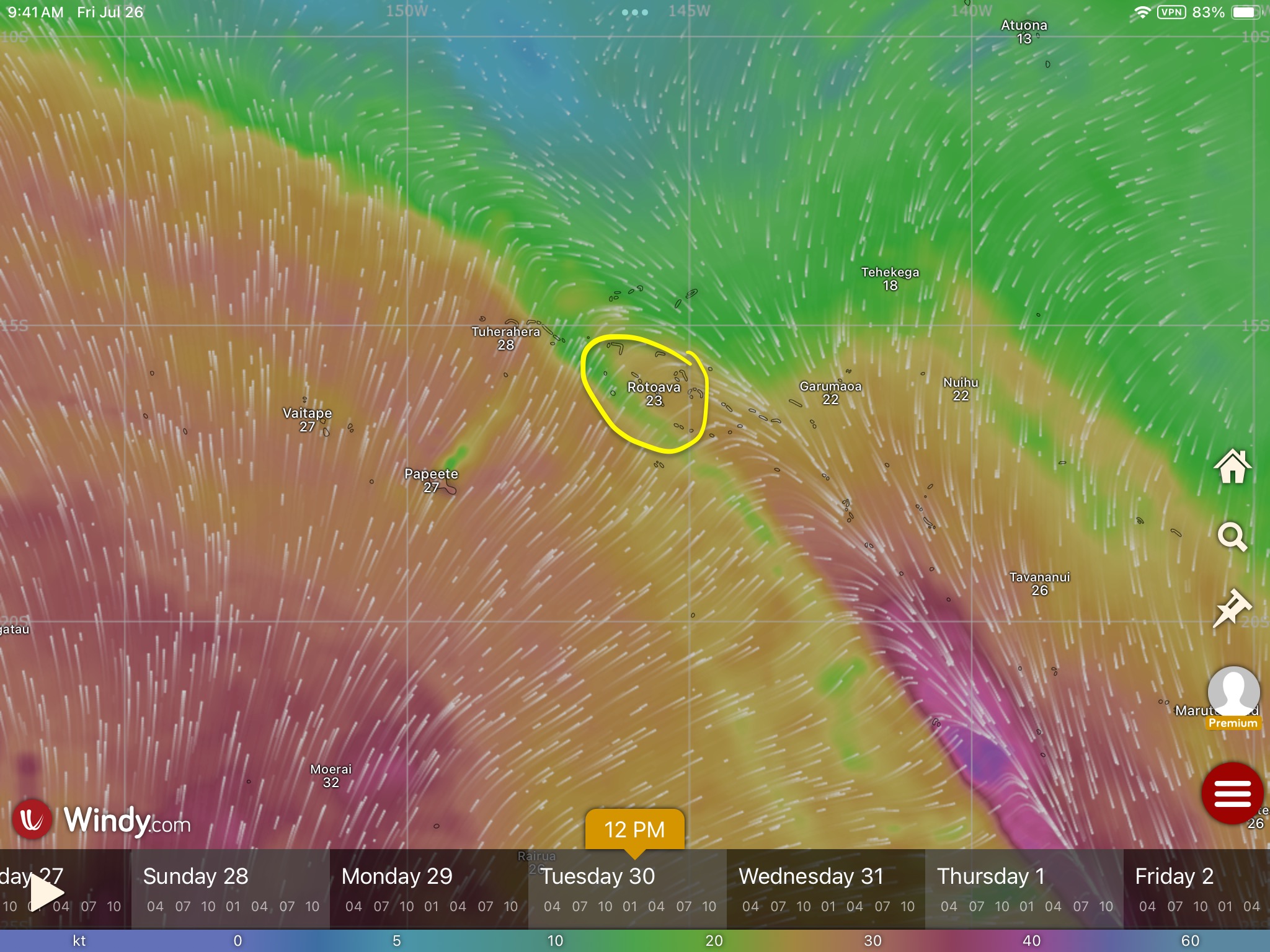

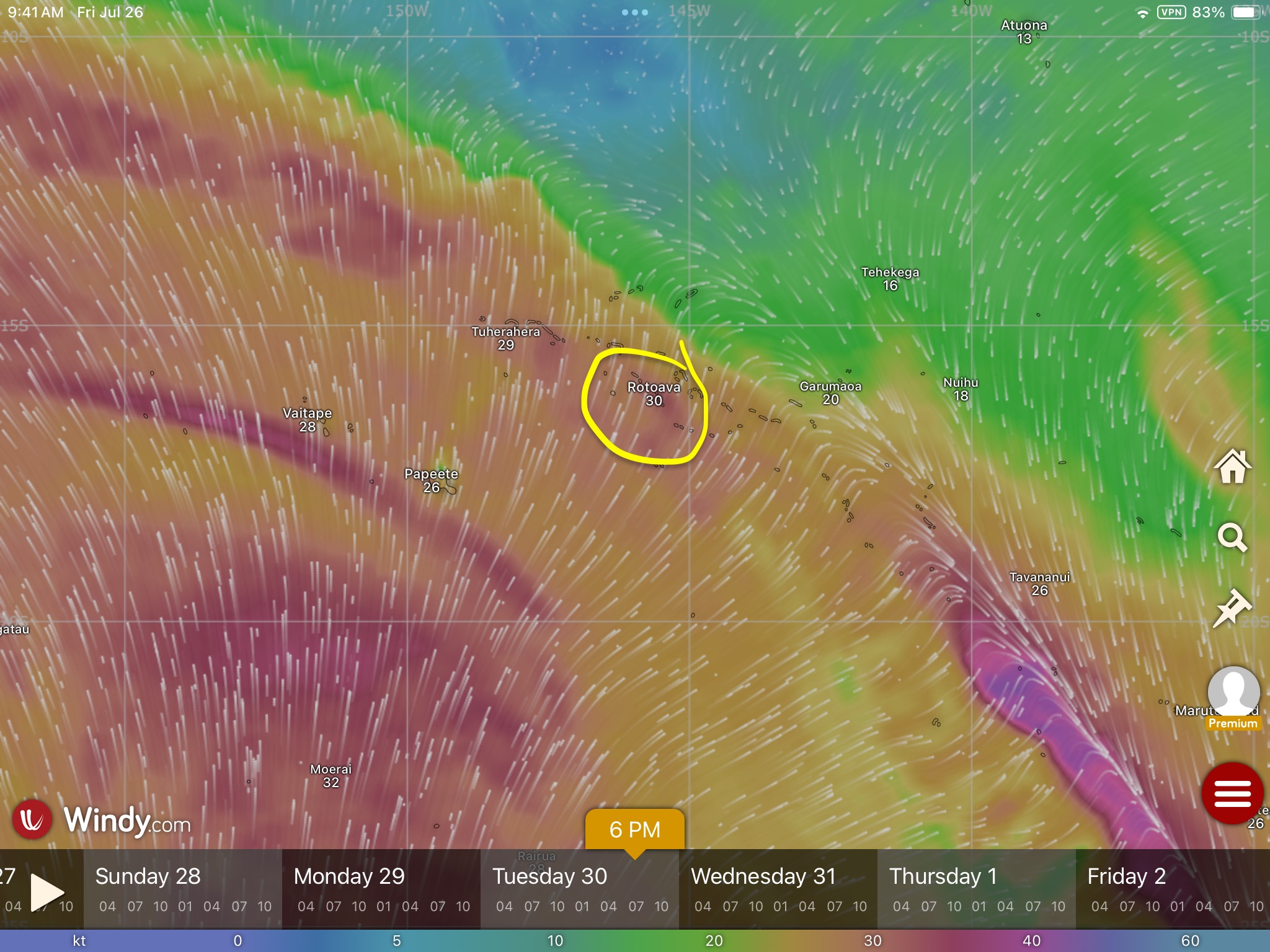

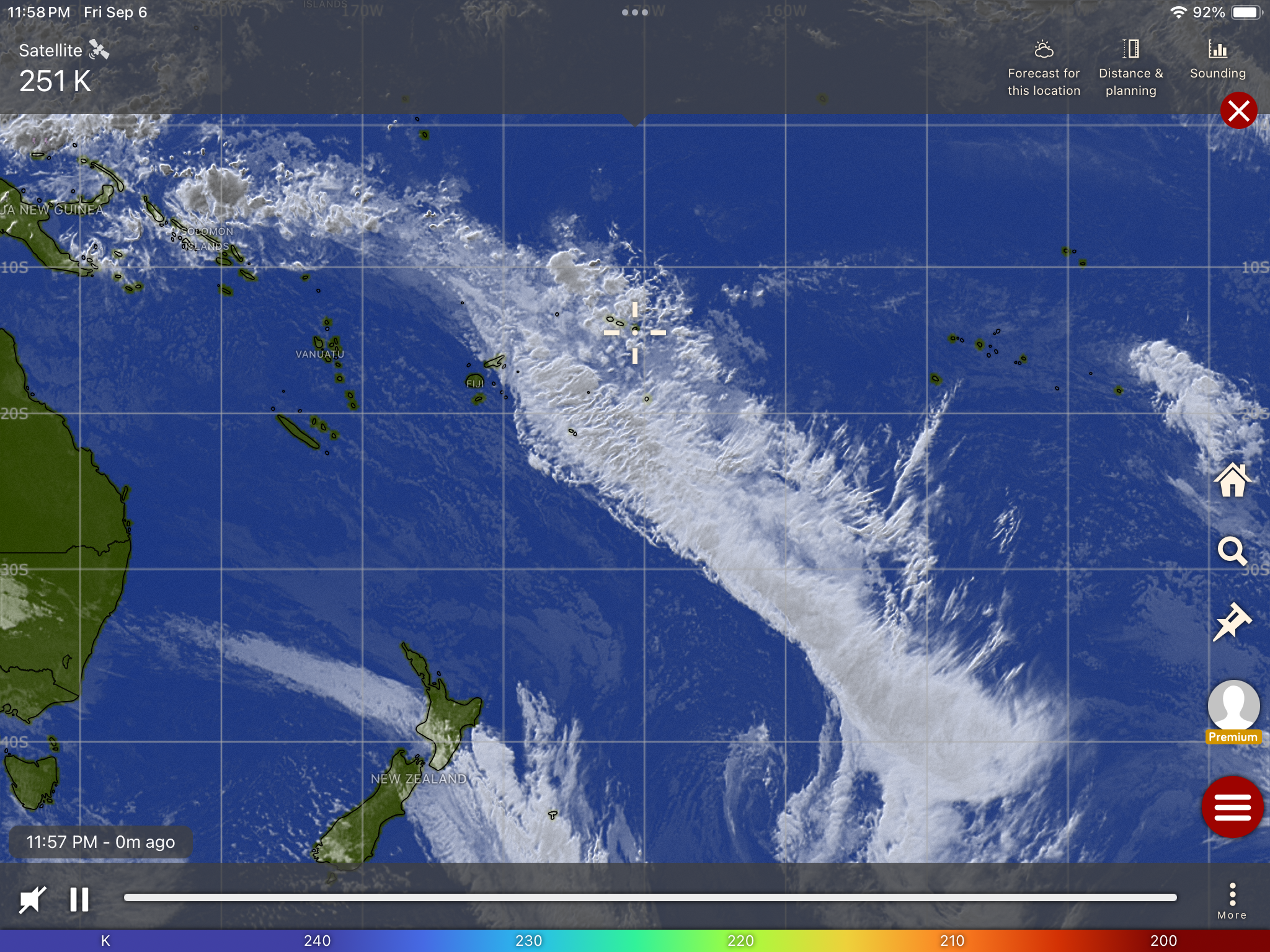

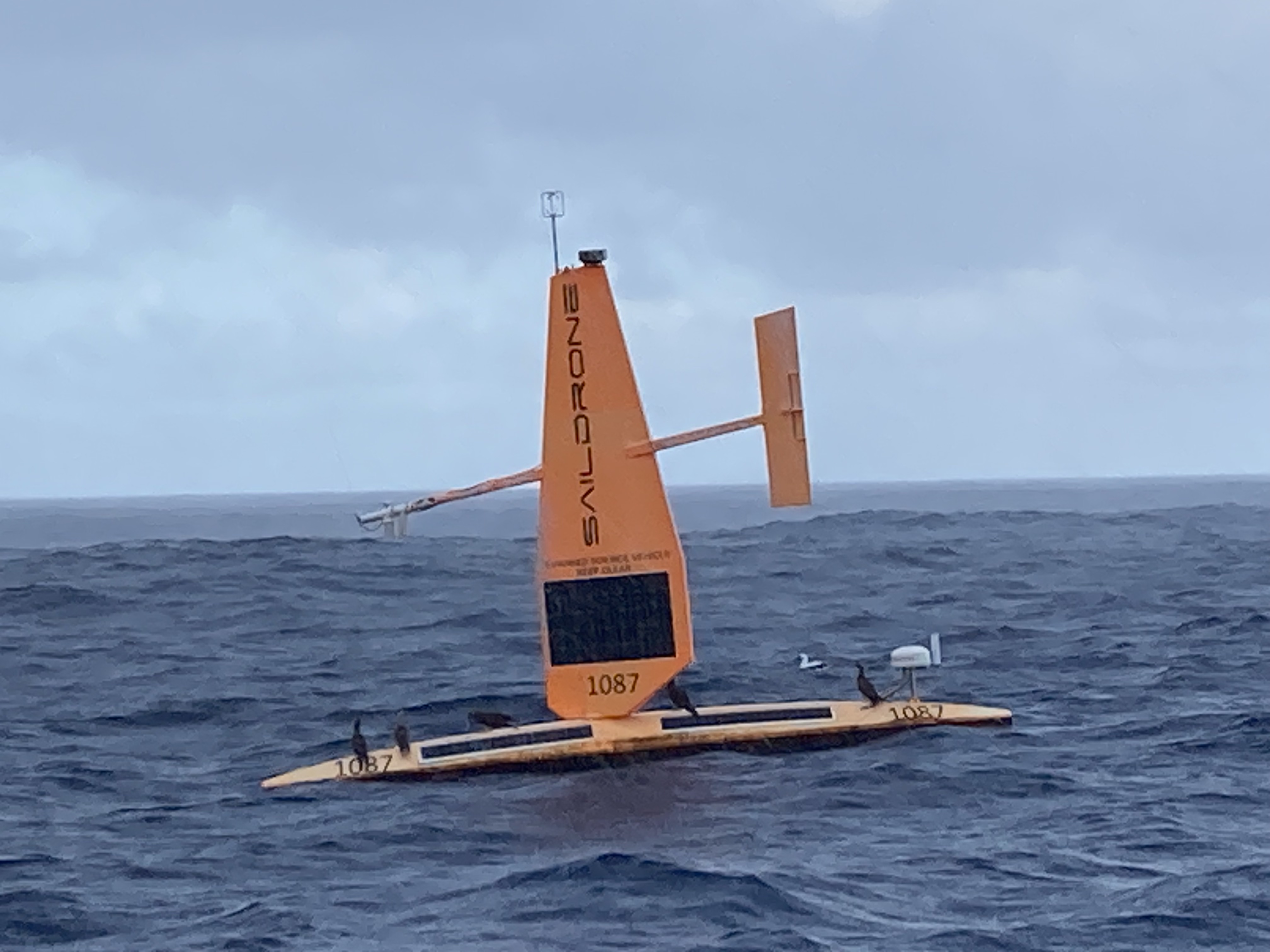

In retrospect, we had spent too much time in French Polynesia awaiting that optimal yet elusive weather window. Still, in the end, our choice to opt for a route that had ended up being over one thousand seven hundred nautical miles – four hundred miles farther than the actual distance separating the Society Islands of French Polynesia from the Kingdom of Tonga – had turned out to be a prudent tactic.

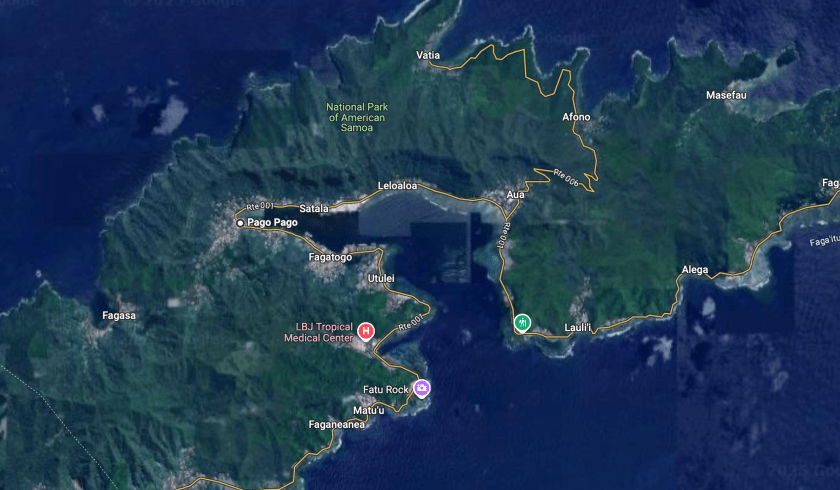

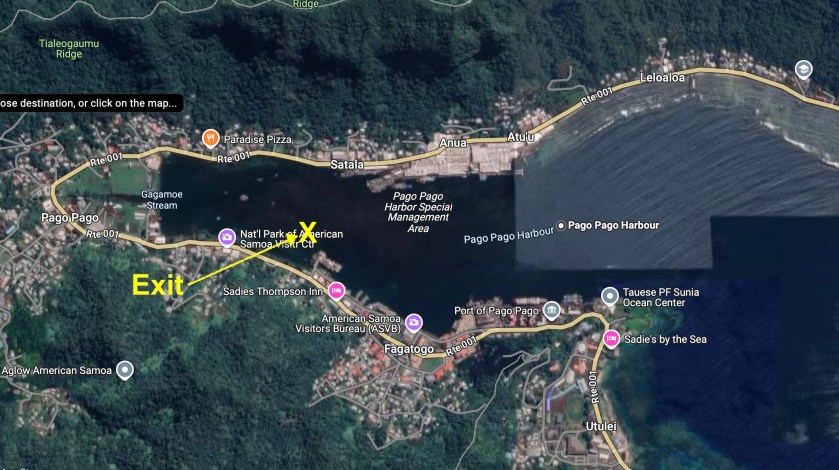

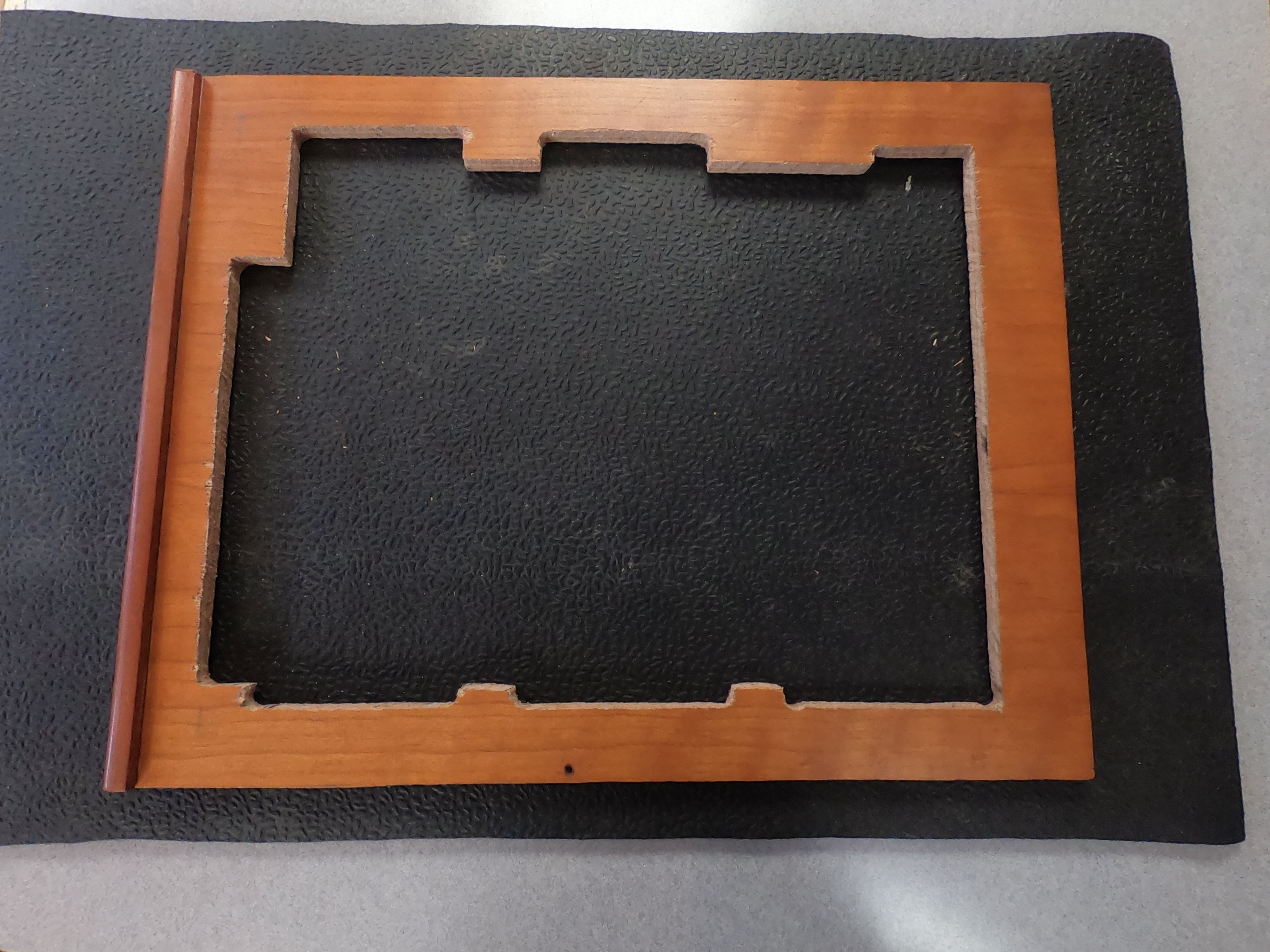

Ironically, arriving at the customs dock at Neiafu to clear into the Kingdom of Tonga on the island of Vava’u proved to be far more adrenaline inducing and nerve wracking than anything during the three hundred sixty nautical mile passage we had just completed. We managed to tie up to the vicious looking cement dock with its rusty rebar poking out, thirty feet directly behind us the definitive outline of a small sunken boat which jutted barely above the surface (obviously sunk while at the dock) and a local fishing boat tied to dock just in front of us. As the tide started dropping and we found ourselves struggling to keep the toe rail of Exit from slipping under the overhanging cement lip of the boat-killer dock we were secured to, we really began to sweat.

However, a short time later the authorities returned with all of our paperwork stamped and in order. We were officially cleared into Tonga. Gleefully, we untied Exit and, thanks to the absolutely benign conditions, separated ourselves from the ominous cement structure without incident.

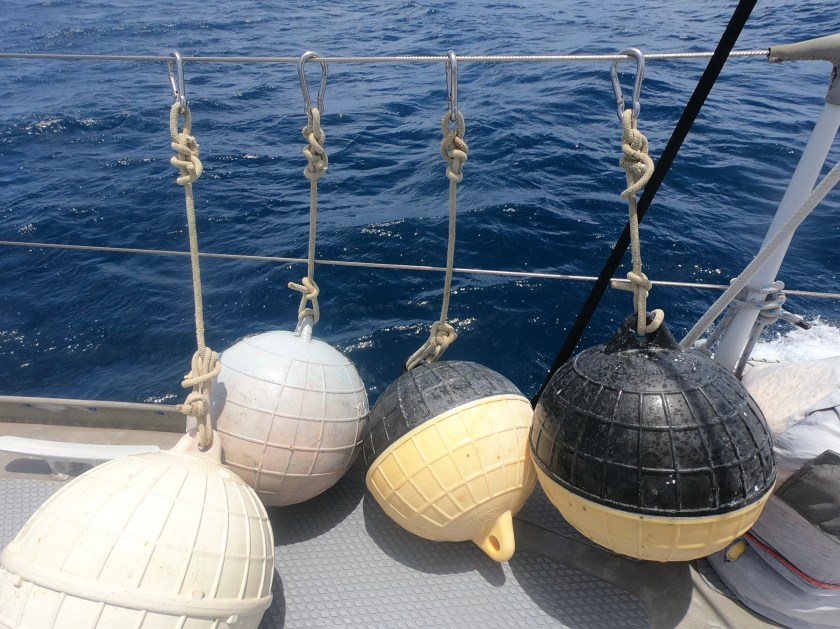

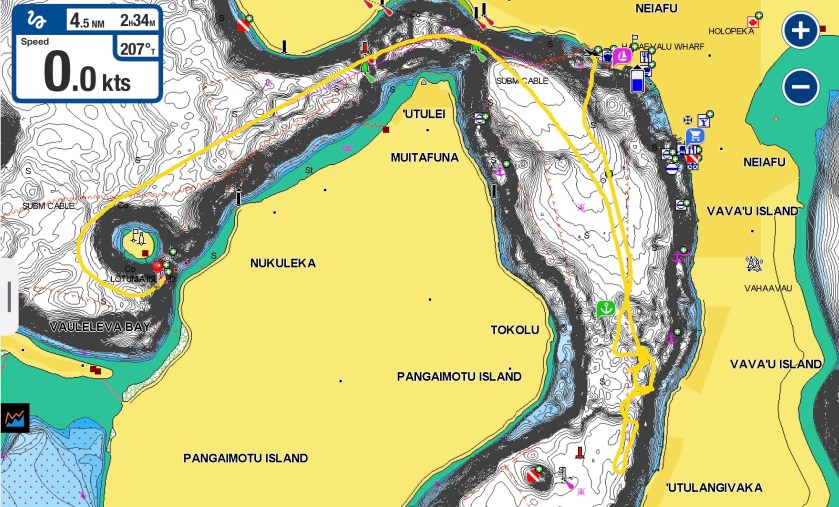

Immediately afterward we were reminded why we so often lament having to be amongst a slew of other boats. Even though there must be at least fifty moorings installed in the bay just off Neiafu, we couldn’t find a single open mooring. Shit.

A handful of scattered mooring balls, obviously reserved only for small local boats based upon how close they were to shore, were the only ones that were unoccupied. Except for one single other mooring ball that had a small inflatable dinghy tied to it. Strange, we thought. But we passed by and continued on.

As we reached the outer edge of the mooring field, we still had found nothing.

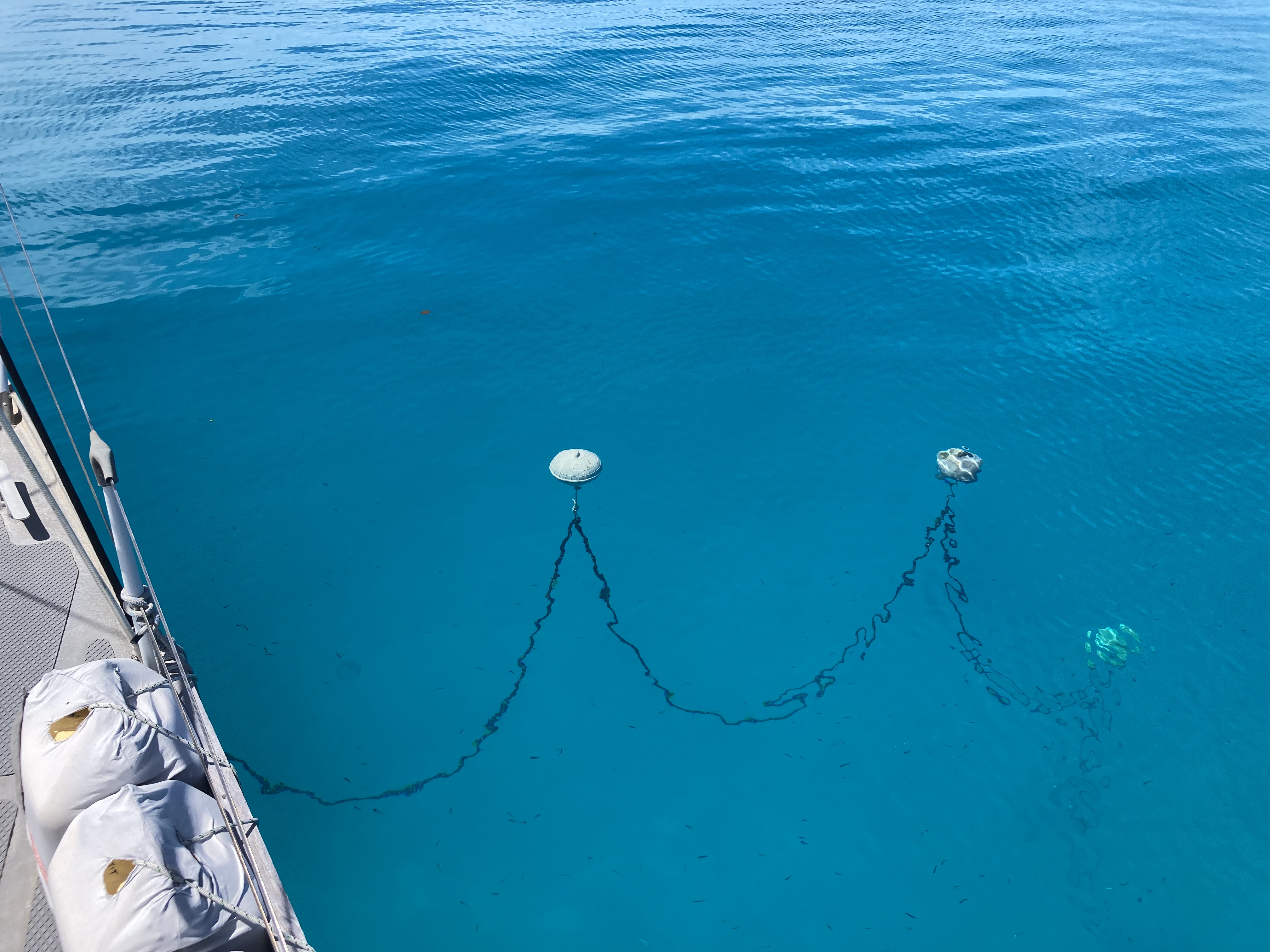

The mooring field, large as it is, takes up only a fraction of the entire bay. One problem with anchoring is it would put the boat at least a half mile away from most of the town. Even more challenging is the fact that just off the shoreline, the shelf is very narrow. To be a reasonable distance from shore (at least by our standards) you find yourself having to anchor in a hundred feet of water.

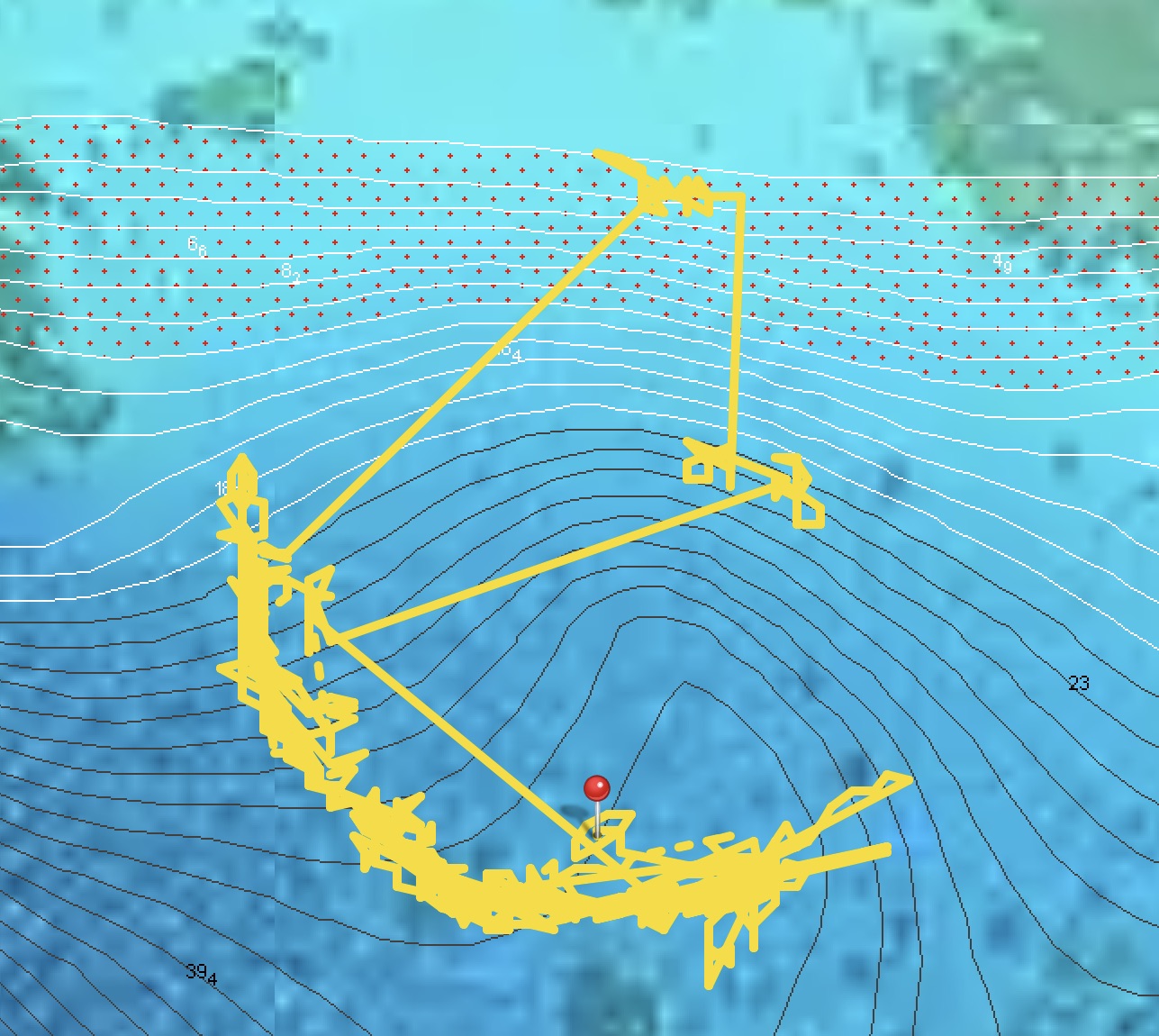

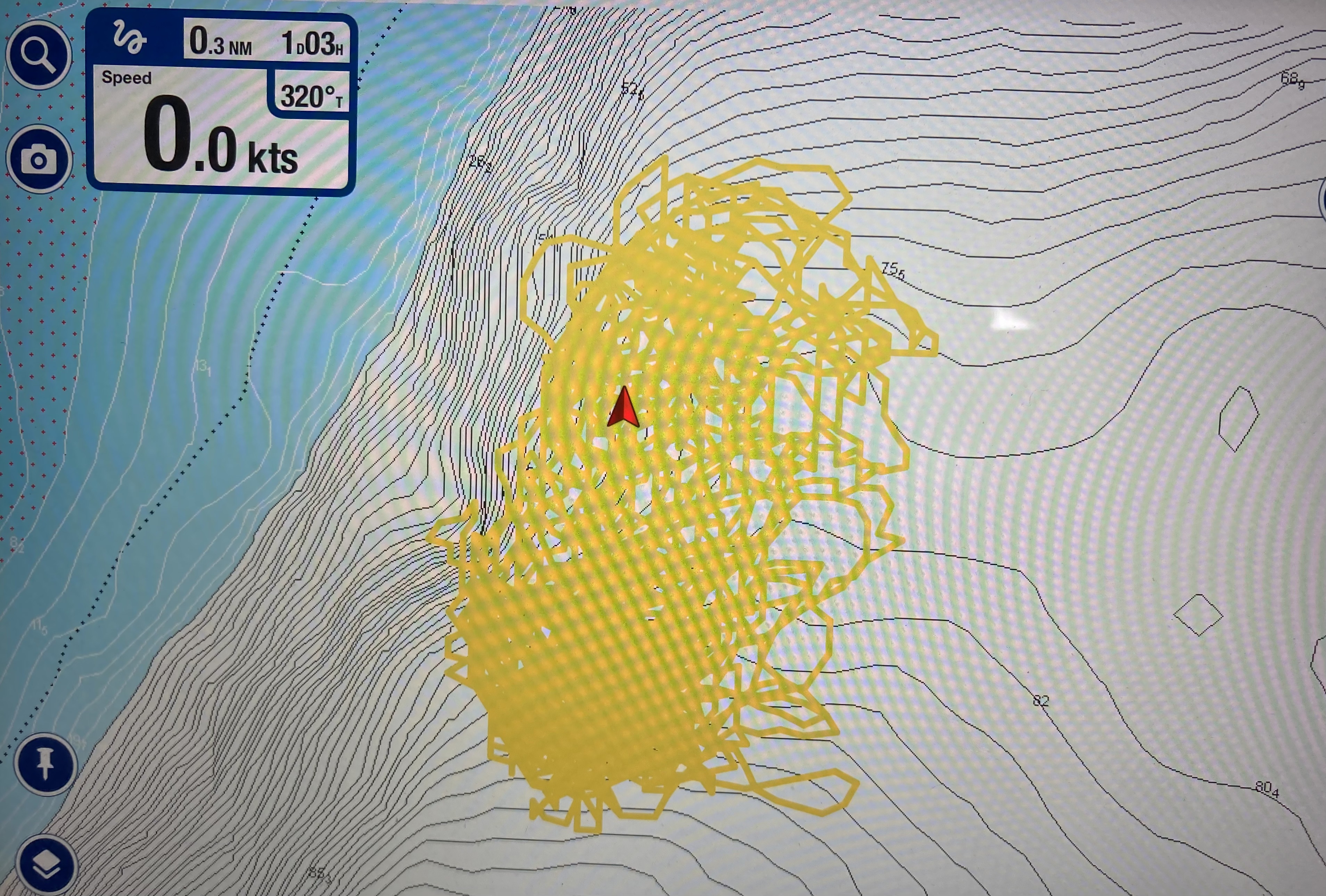

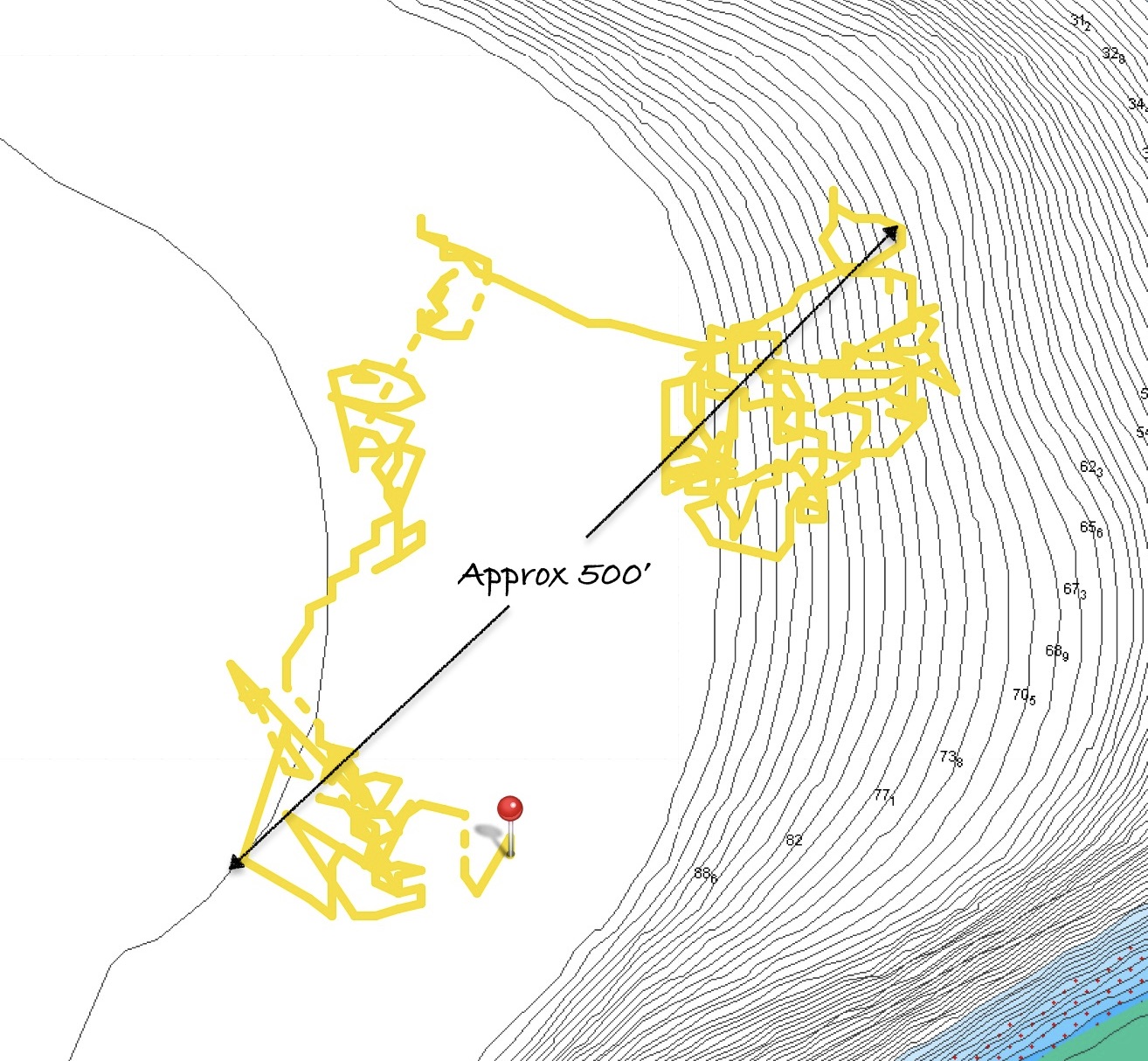

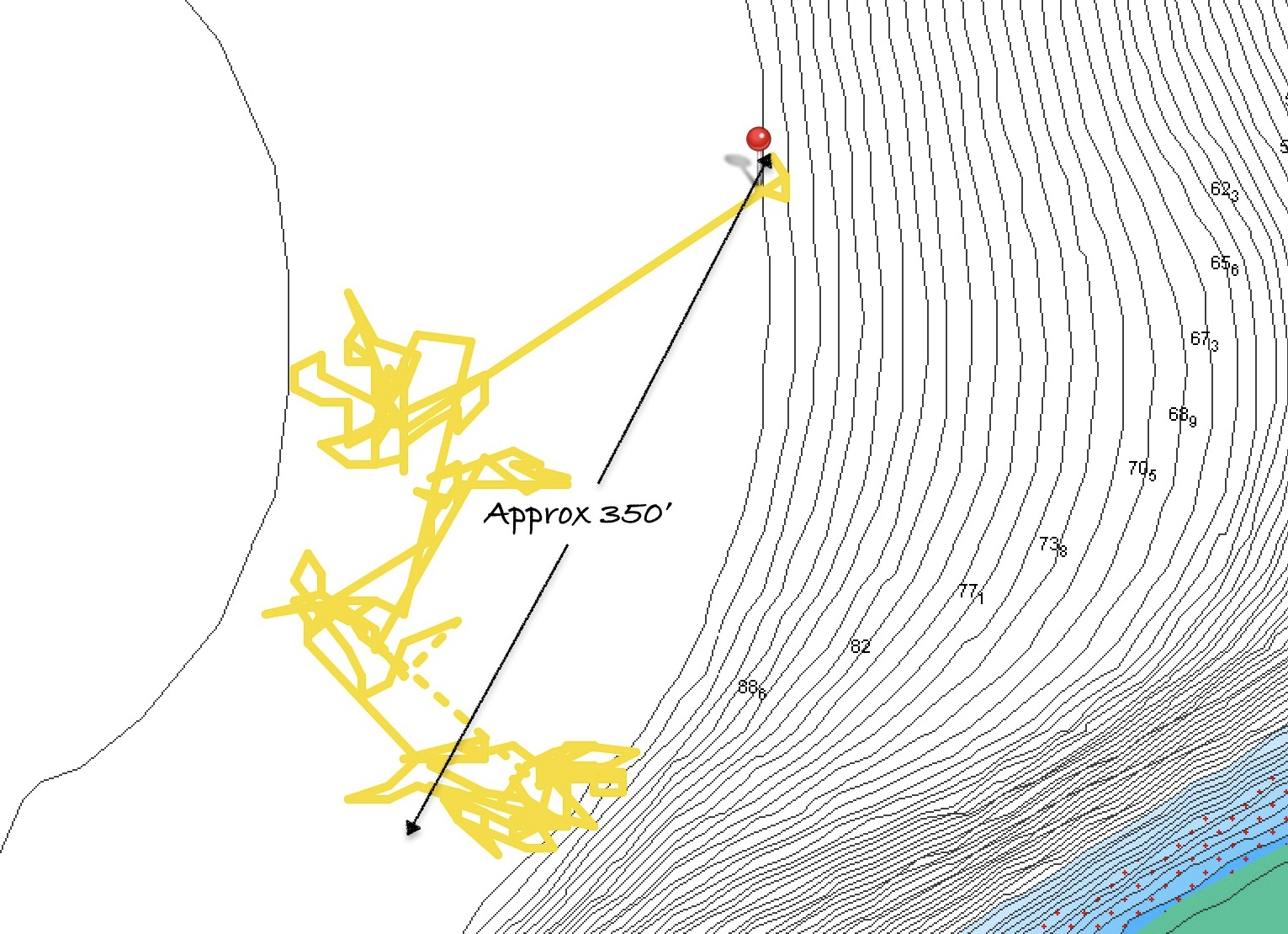

For us, a ten to thirty foot depth is ideal for anchoring. Forty to sixty, though not a problem, starts putting the boat on a pretty damn large diameter to potentially swing if you have a reasonable amount of scope out for the chain. One hundred feet is getting pretty ridiculous. Doable. But with all of our 350′ of chain out in a hundred feet of water, we are still at less than a 4:1 scope; and now have the potential of swinging in an arc larger than a football field if the wind were to reverse 180°. That’s fine when we’re the only boat and we have the space. But, really? Here we knew we would be lucky if a boat that chose to drop anchor next to us allowed even a hundred feet of space between us.

And yet, we were pretty limited on options for the moment. We decided to drop anchor in deep water, hoping that someone else would choose to abandon their mooring in favor of heading out to one of over forty charted anchorages in the area.

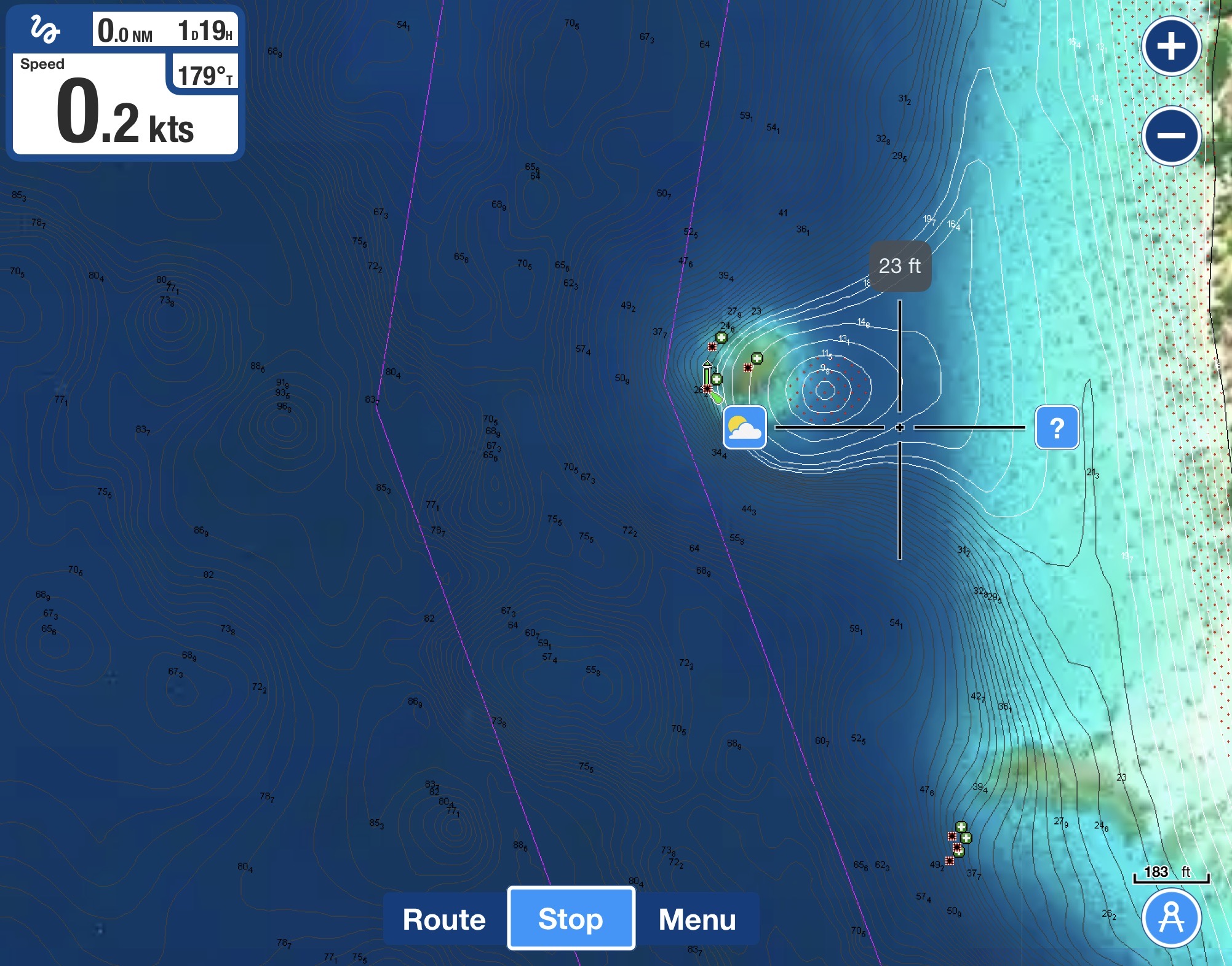

We crept as close to shore as we dared, trying to get slightly shallower than a hundred feet, and dropped anchor in eighty five feet of water. Initially we couldn’t get the anchor to set. Then, after a couple of tries, we both concurred that we were simply too close to shore for comfort…especially if we were finding the holding marginal, as seemed to be the case. Having just arrived, we really didn’t know how breezes would play out in the bay, nor how consistent the wind direction would be. It wasn’t worth the risk.

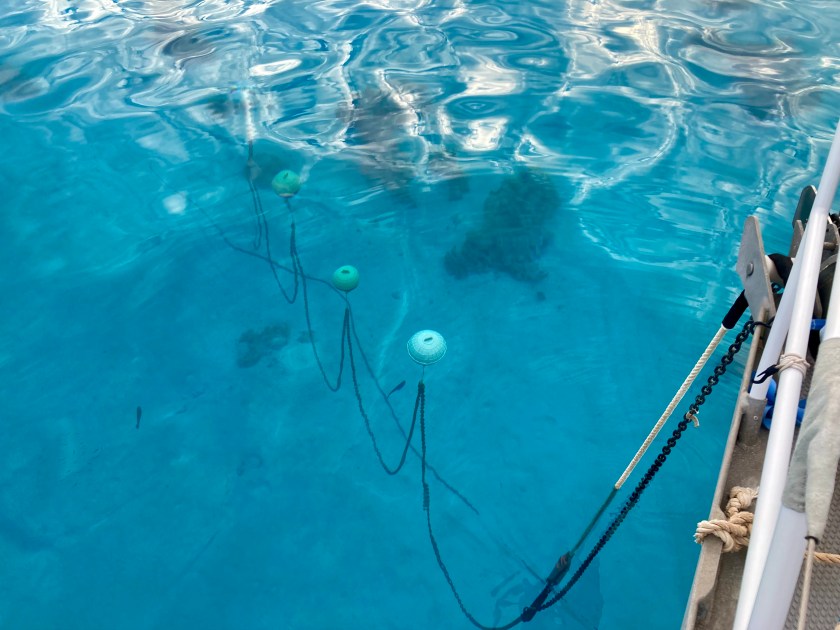

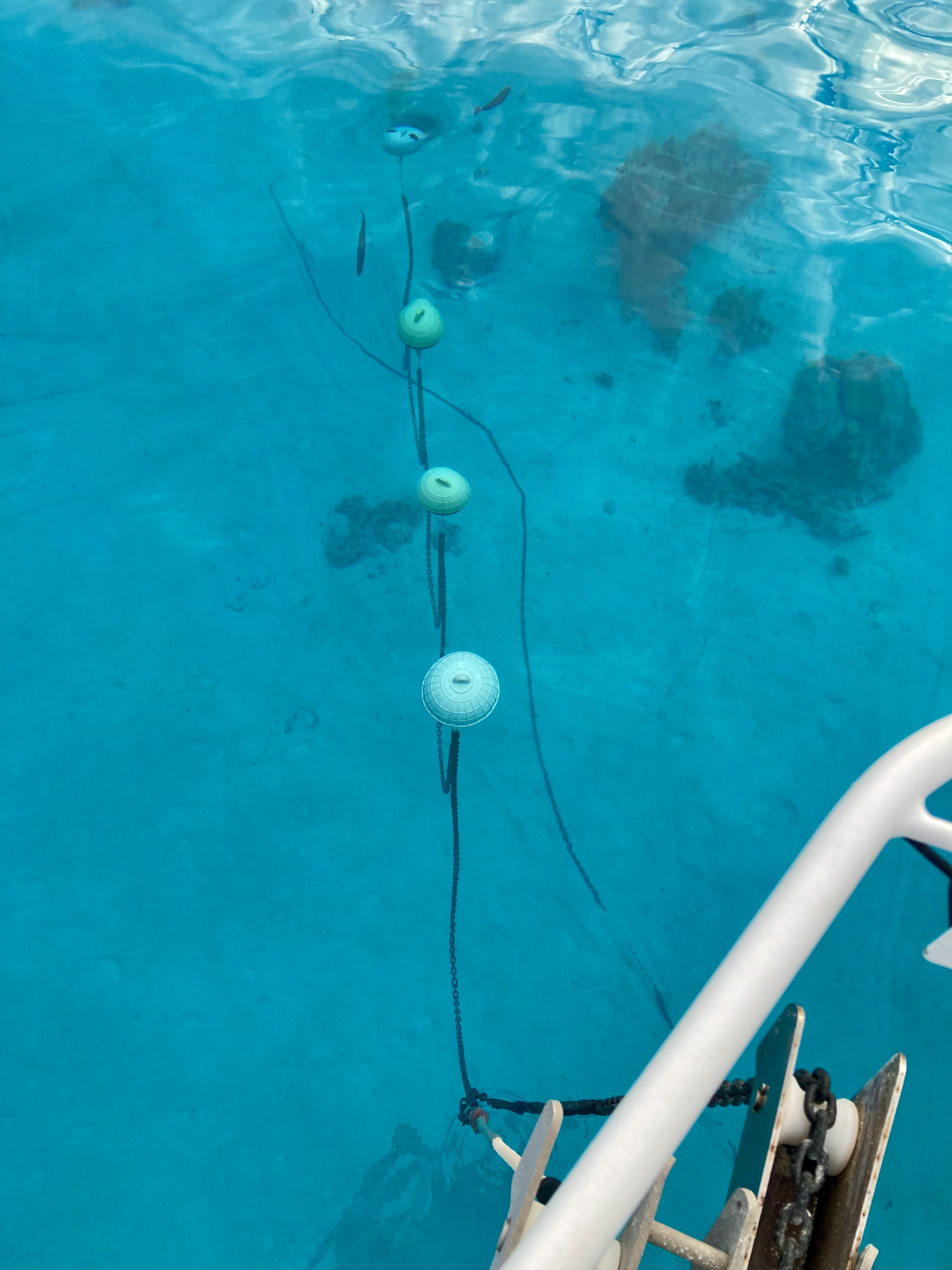

As we started pulling up the chain, it stopped dead with over a hundred fifty feet still out.

Damn. We were fouled on something. Not a big deal.

But after a few minutes it became clear that it wasn’t just a snag. We were really stuck…again. We had just gone through this in American Samoa – probably our worst experience ever with a fouled anchor chain…until now. Fuck.

Once again, we found ourselves wrestling for over an hour struggling to free the chain. Once again, we found ourselves almost deciding to don scuba gear to sort it out. Double fuck.

Then, once again, as we neared the tipping point of frustration becoming rage, the damn thing came free. Arggggggh!

Five minutes later, as we motored back through the mooring field making one last search for what we hoped was an empty mooring ball we had missed earlier, the point from frustration to rage didn’t just tip – it was smashed.

The mooring ball we had passed by earlier with the dinghy tied to it now had a sailboat flying a yellow ‘Q” flag pulling up to it, with two people at the bow holding a boathook and lines to tie off with. Triple fuck.

Some asshole had used their own dinghy to reserve the last mooring right next to their boat for a bunch of jerkoffs that were arriving after us. Perfect. Thanks S/V Faraway. Another awkward reminder as to why I hate most people…especially those that own boats. At least I got to smile a few days later when I heard that they had blown out their spinnaker…ain’t Karma a bitch?

Kris scowled at me as I held up my middle finger while we passed by. I was furious, venting how we should have just pushed the dinghy aside and tied up to the mooring ball earlier. Fortunately, Kris’ cooler head prevailed and we said screw the mooring field, opting to anchor just off a small island a couple miles outside of town.

It had been two and a half hours since we had left the cement government dock. The engine had been running the whole time. Almost the same amount of time we had run the engine over two and half days getting here all the way from American Samoa. Only this time, we had travelled a whopping four and a half miles instead of nearly three hundred sixty…quadruple fuck.

These were some hard earned anchor beers we were gonna enjoy.

The following day we returned to the town. There were half a dozen unoccupied moorings…of course.

Unbeknown to us, we had arrived just as the week long 2024 Vava’u Sailing Festival was commencing. It offered us great insight into our new location, multiple presentations about potential future destinations in New Zealand, a number of opportunities to meet some locals, ex-pats, and other sailors, a fascinating and entertaining day trip to a cultural event, and some free meals. All in all, a win.

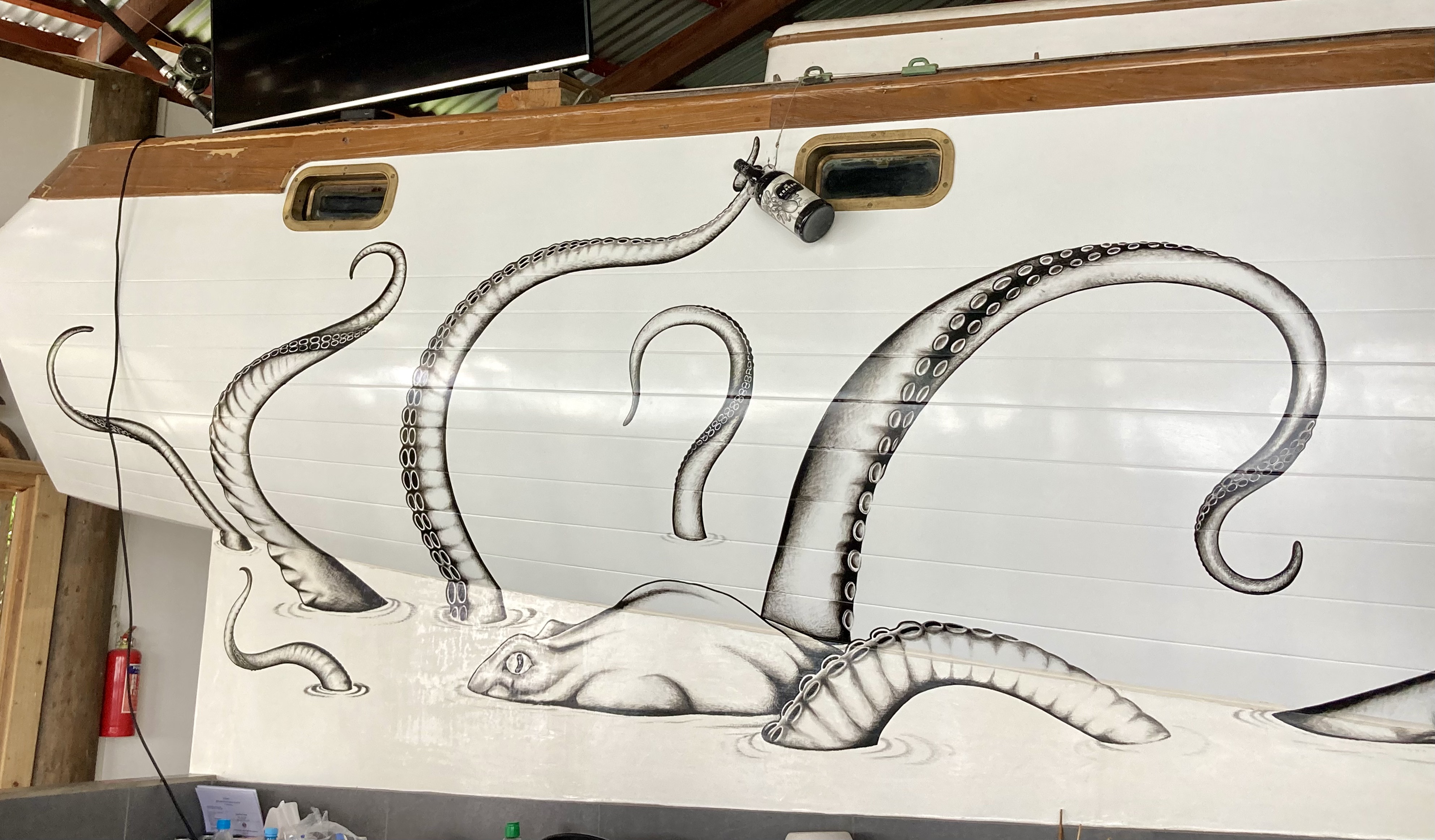

We were also introduced to The Kraken bar, where we spent a number of evenings enjoying food, conversation, and of course our favorite Kraken rum. It even had an actual sailboat, complete with Kraken graphics, integrated into the bar’s interior decor. As it turned out, they served a variation on the famous sailors’ drink of choice – “Dark and Stormy” (made from Pusser’s Spiced Rum and Goslings ginger beer). Mixed with Kraken spiced rum and Bunderberg ginger beer, “The Kraken”, as they called it, was the exact same drink we thought we had invented and named “Perfect Storm” years before!

By the end of the first week we felt well informed, privileged to be amongst such a hospitable group of Pacific Islanders (it immediately became apparent why the the Kingdom of Tonga is referred to as “the Friendly Islands”), as well as exhausted from all the social interactions. Having talked to more people on boats in five days than we had in the previous five months, we decided to restock some of our provisions and get the hell out of town.

We just had one task to accomplish beforehand.

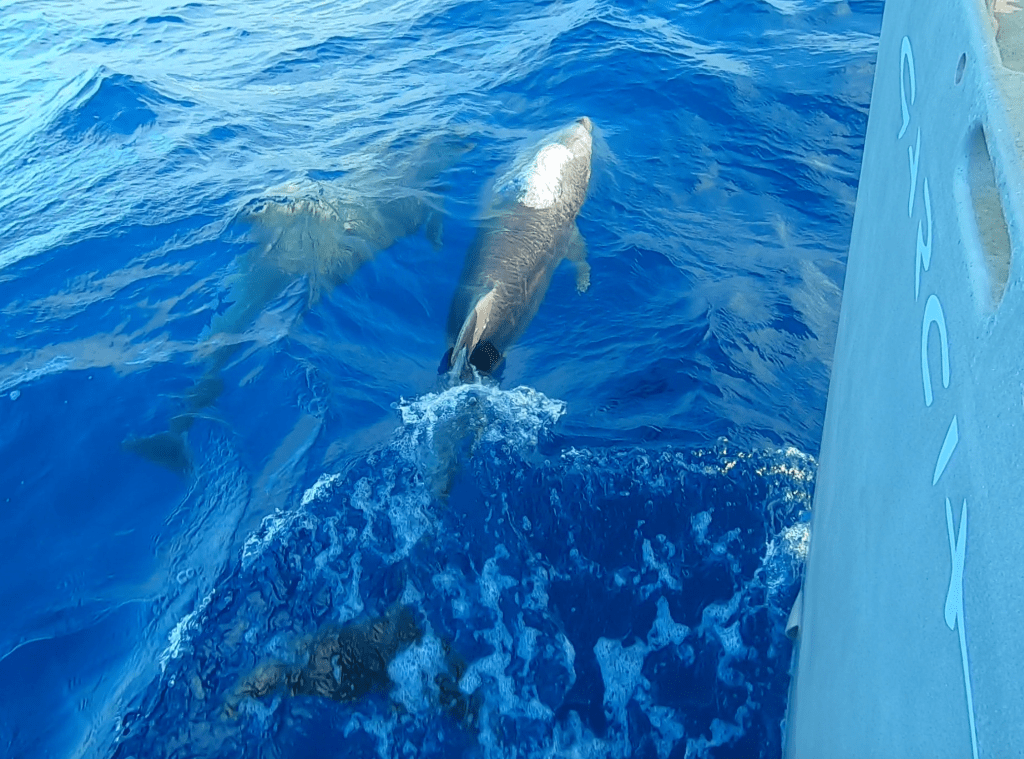

During our arrival to Tonga we had already experienced an amazing though brief whale encounter. Just as we were sailing into the channel entrance, we were greeted by a mother humpback whale and her calf. They were about five hundred feet away, but it was unbelievable…who could ask for a better welcome?

Every year, Tonga acts as a brief rest stop for humpback whales and their calves migrating to Antarctica. This certainty has provided Tongans with the opportunity to build a very respectful and conscientious tourism industry around seasonal whale watching encounters. It is also one of the only places on the planet where you can actually swim with these stunning creatures.

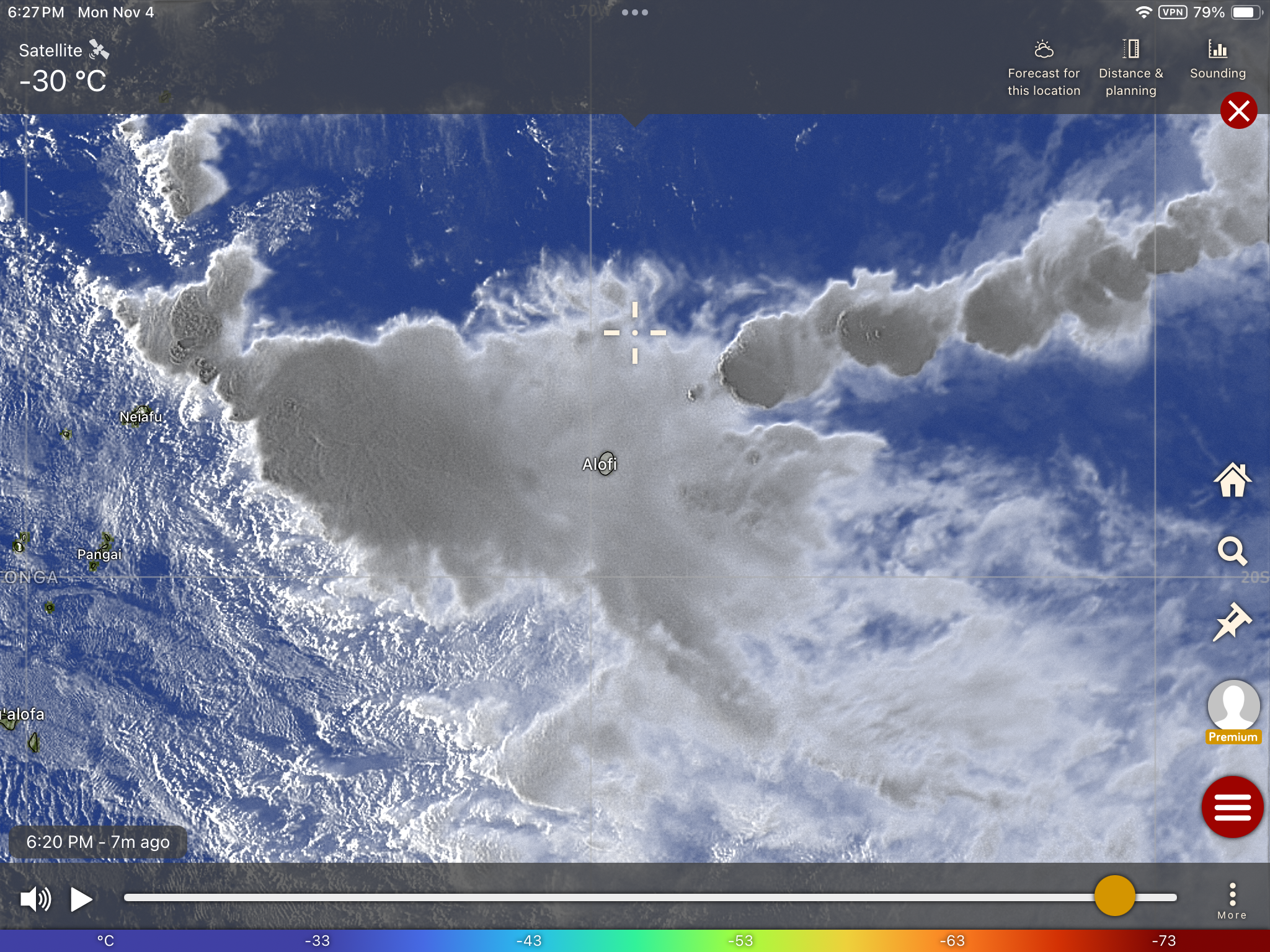

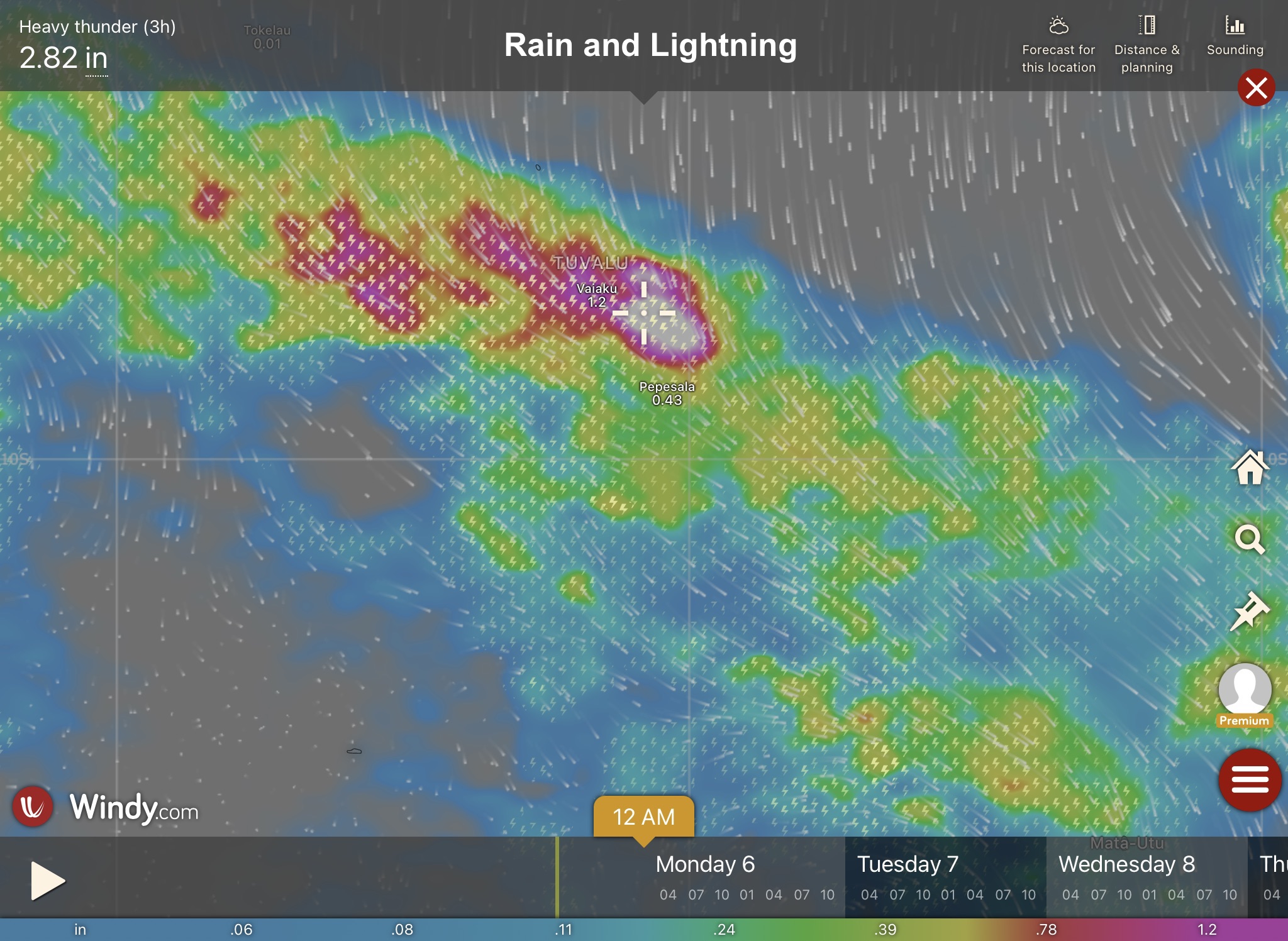

During the sailing festival we had learned that the numerous whales in the area, mostly mothers with their young calves and an occasional escort, had already begun departing, cued by the cooling of the surrounding waters. While these whales could often be spotted until the beginning of November, this year an early temperature drop in the water had triggered an early exodus. The locals believed that by the second half of October, the whales would all have already moved on.

The locals were also abuzz with reports of an albino baby humpback who had been seen recently this season. It was the first time in Tongan history that an entirely white albino calf had been seen, and as such, also spurred quite a lot of conjecture as to its mystical significance.

We held no expectations of a White Whale encounter (the albino calf’s wary mother had already understandably grown tired of all the excess attention they had received and likely moved on), but we had every intention of seizing the dwindling opportunity to swim with these magnificent mammals before the last ones departed.

Those in the tourism industry must walk a thin tightrope when balancing between tourist experiences and what is best for nature. Oftentimes the result is a shit show. In this case, it seems to be done admirably. In Tonga, whale interactions can only legally occur under the presence of a guide, limited to snorkeling at the surface, with only one boat in proximity and no more than four people (plus the guide) in the water at once. Boats aren’t permitted to chase whales and the guide must assess the demeanor of the mother and her calf before anyone is even permitted in the water.

The company that took us out was very professional, courteous, and conscientious. However, as is always the case, Mother Nature can be very fickle and the luck of the draw inevitably comes into play with the day’s outcome. A two hour mechanical setback on a boat that was slow to begin with, dwindling numbers of whales in the area, rough conditions that limited where we could go (especially with two young children aboard) all made for a challenging day. Furthermore, eight people aboard the boat meant any time in the water had to be split between two groups.

Eventually, we did see whales. Our group of four (myself, Kris and another couple) got in the water with a mother humpback, her calf, and a third escort. The moment was fleeting…seconds instead of minutes. Still, it was magical. And then they dove and were gone. When we came across another mother humpback and her calf a bit later, one of the two children in the family of four decided he didn’t want to get in the water, allowing Kris a second opportunity to enthusiastically jump in the water for an additional breathtaking, though brief, encounter.

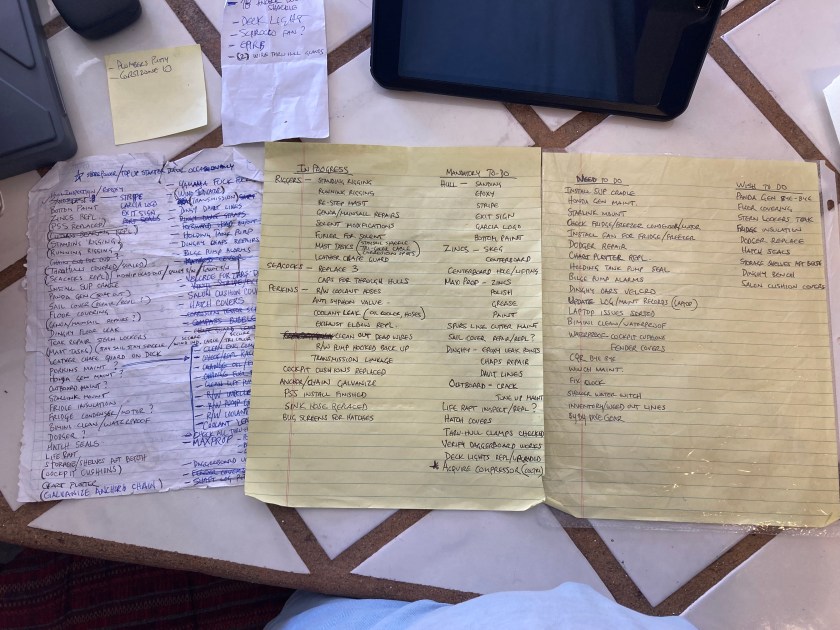

We returned to Exit at the end of the day feeling simultaneously giddy with excitement and slightly guilty for a sense that things had fallen a bit short. After a great deal of discussion we decided to set aside our trepidations, ante up and roll the dice again, with a different company this time.

We weren’t disappointed…a faster boat with no mechanical issues, only four of us this time, a fantastic guide, and sympathetic Mother Nature. Jackpot! Our patience and persistence was rewarded with an absolutely brilliant day.

I think it would be fair to say Kris was more than a little stoked about the whole affair. But who’s kidding who, so was I.

Afterwards, we took a brief detour to a submerged cave known as Mariners Cave before returning to town.

The phenomenal whale interactions had far surpassed our wildest expectations, not to mention our budget. Sometimes life altering experiences like those can’t be judged on cost. They are too far and few in between; and, as such, need to simply be taken in for the magic they create.

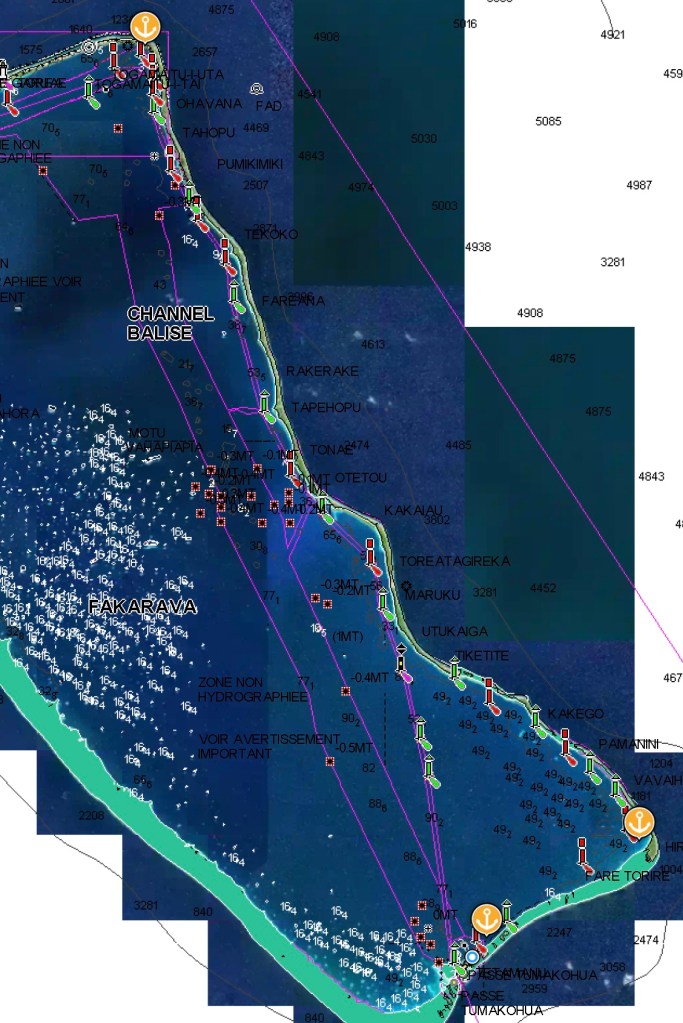

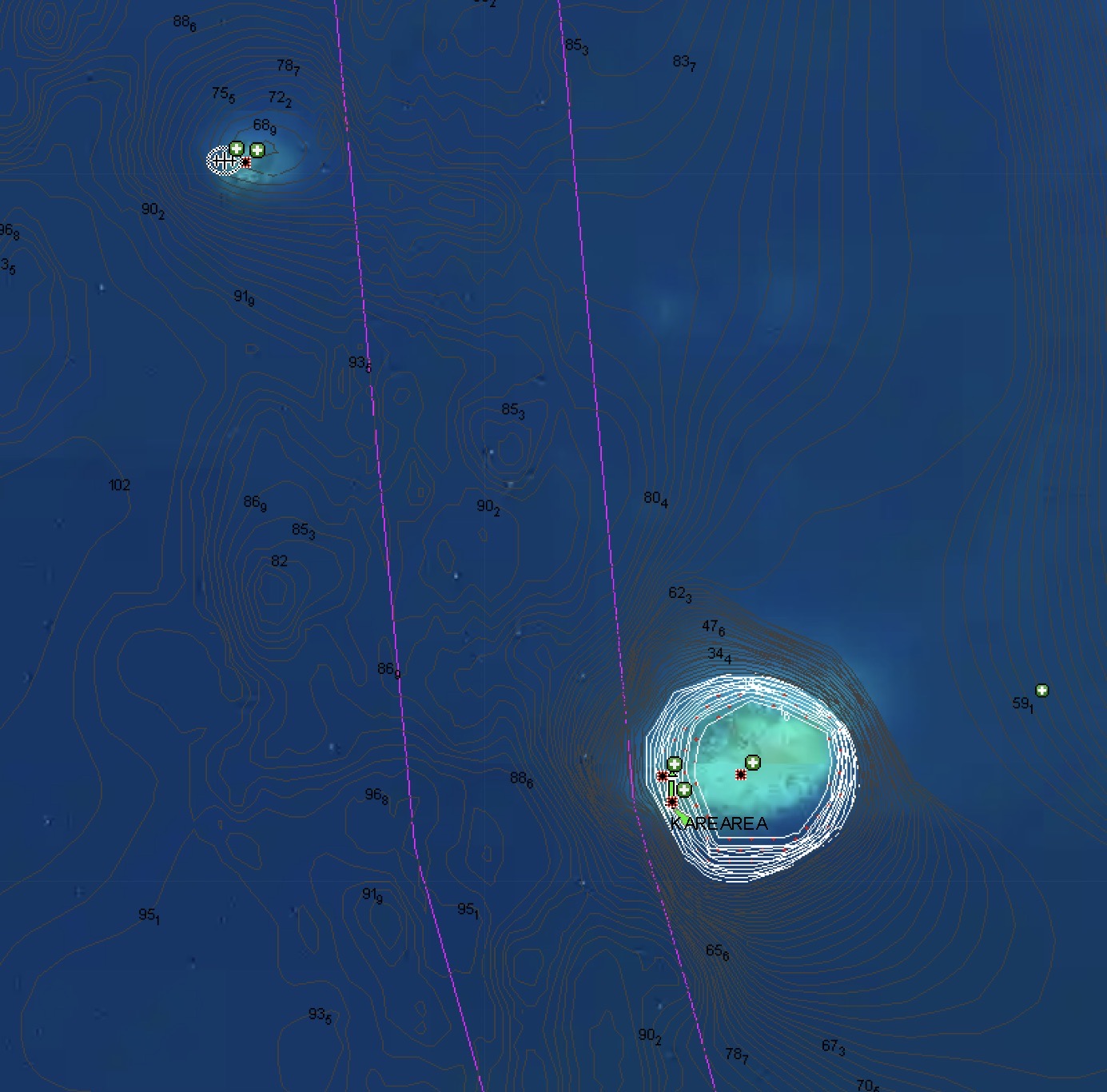

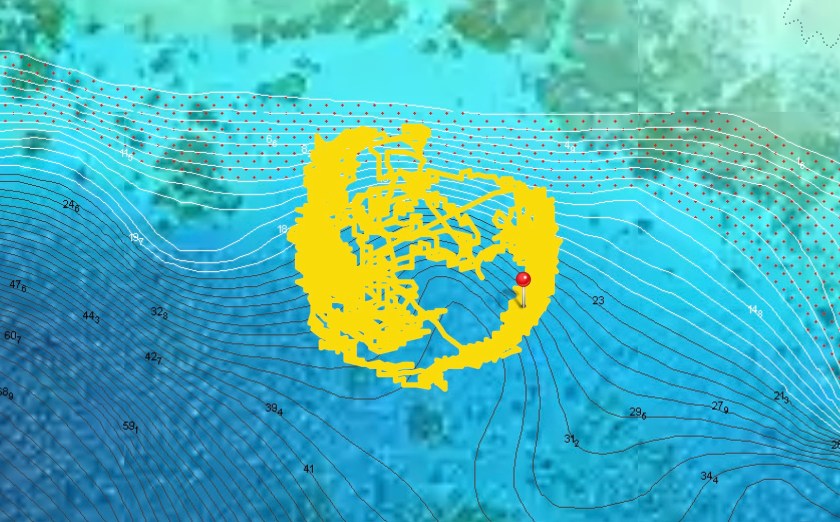

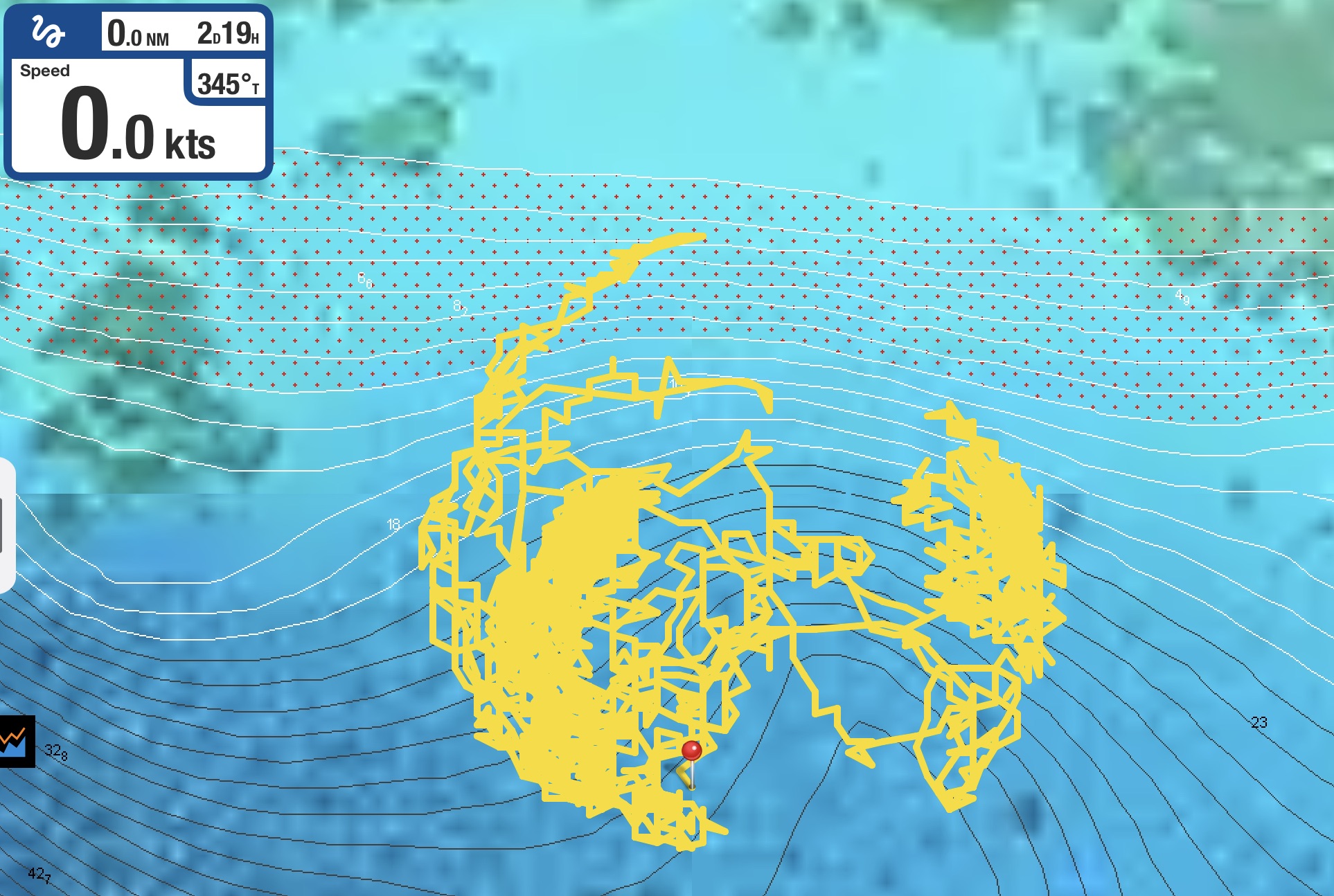

Still, when money is not an infinite commodity in one’s possession, there has to be a balance. The pendulum needed to swing back in the direction of zero expenditures for a while, so we set out to explore some of the anchorages scattered throughout the network of islands around Vava’u. With over forty charted anchorages, we had plenty to choose from. We also learned long ago that noted anchorages represent only a fraction of the actual possibilities.

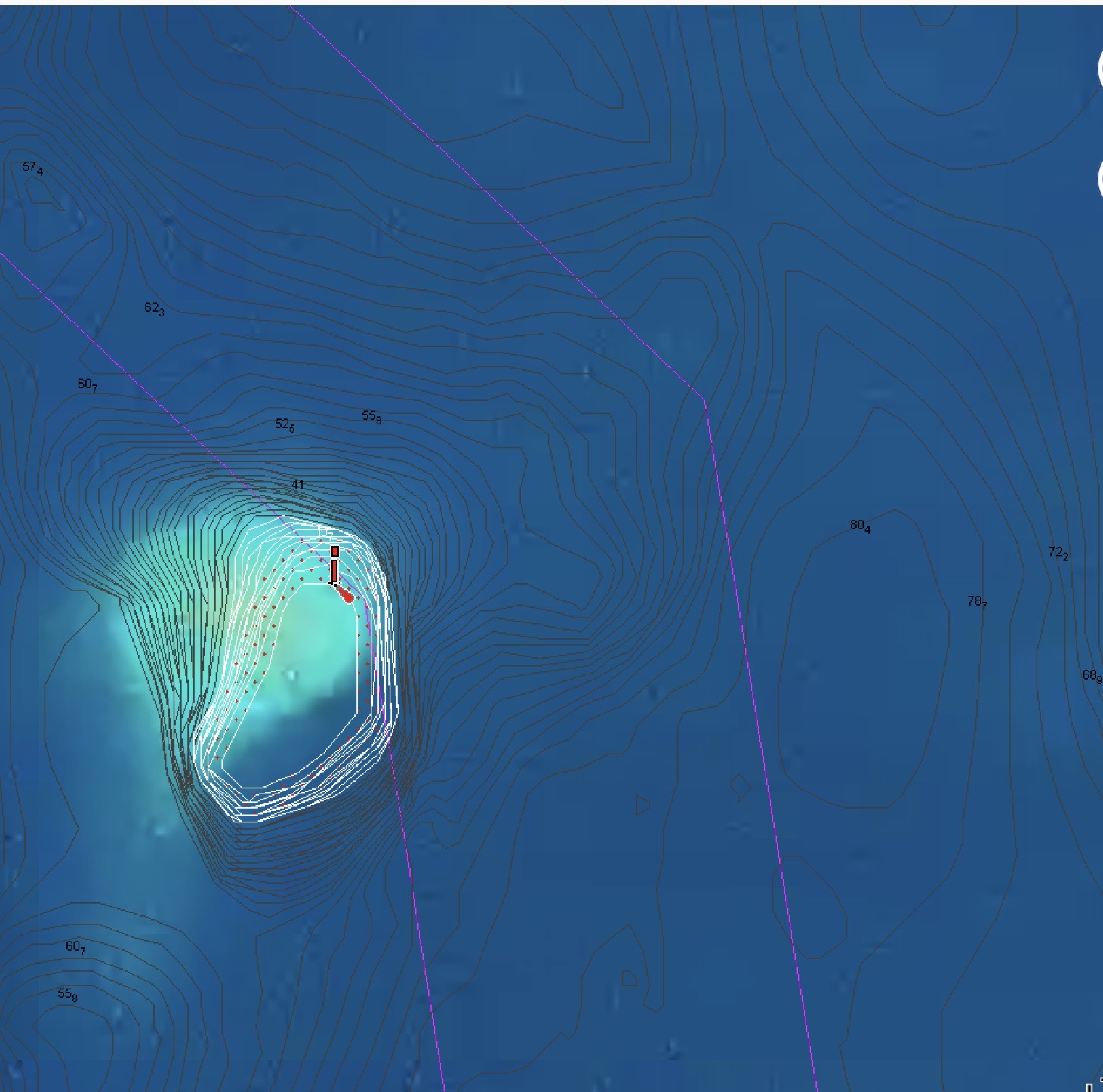

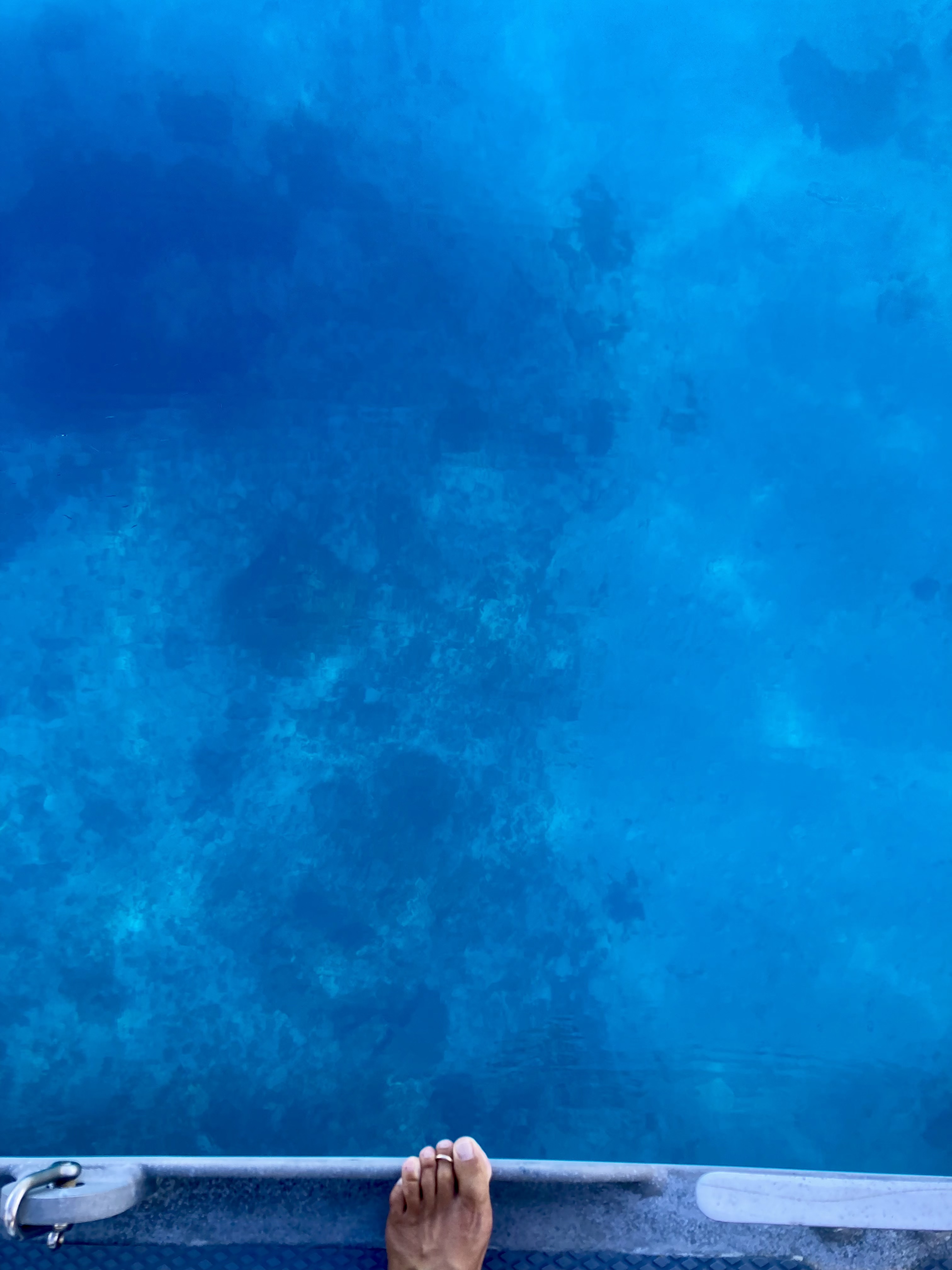

During a stretch of particularly calm weather we took advantage of the opportunity to sail to one of the outermost islands in the Vava’u chain, an island named Kenutu (#30 on the map of charted anchorages), where we found ourselves completely alone in an unbelievable and picturesque setting.

A hike to the far side of the island provided a fantastic view of the open ocean side.

Given our isolation and the stunning view, we decided this was a perfect location to launch Space Exit. The perspective offered by a drone a couple of hundred feet in the air is so completely different from our typical orientation that it never ceases to amaze us.

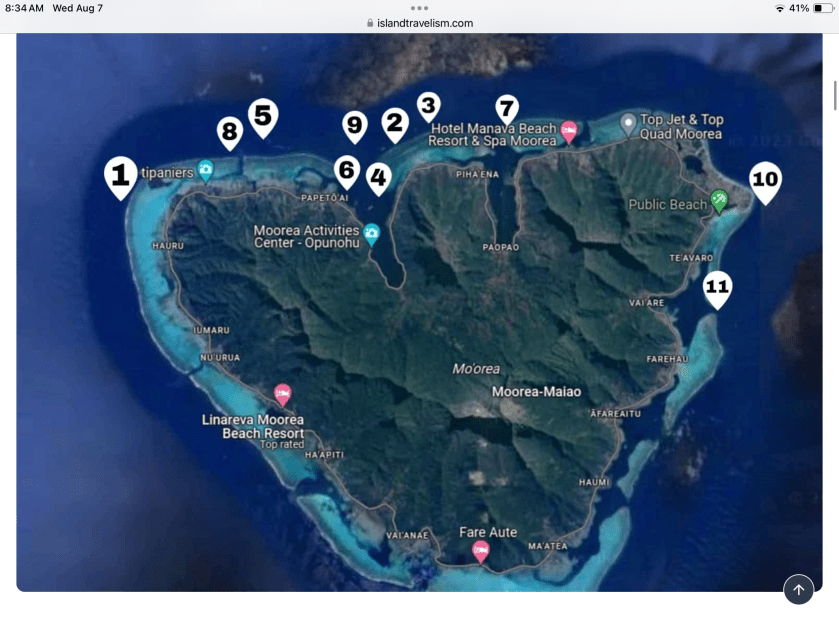

During a different excursion to another anchorage we found ourselves within range of a dinghy ride to a popular spot called Swallows Cave. Though that cave was hopelessly overrun by other tour boats and sightseers when we arrived, we found the smaller cave right next to it to be well worth the journey.

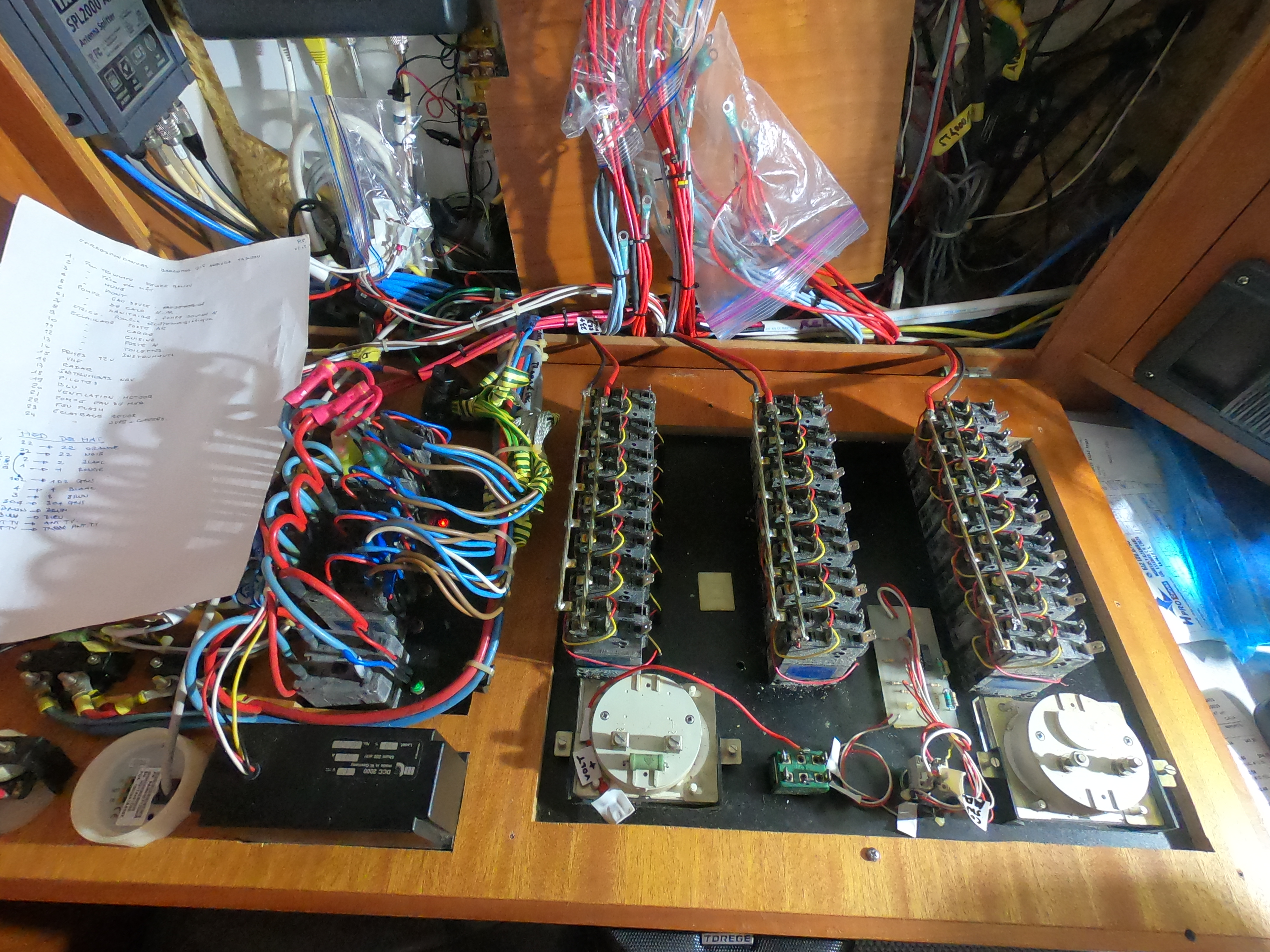

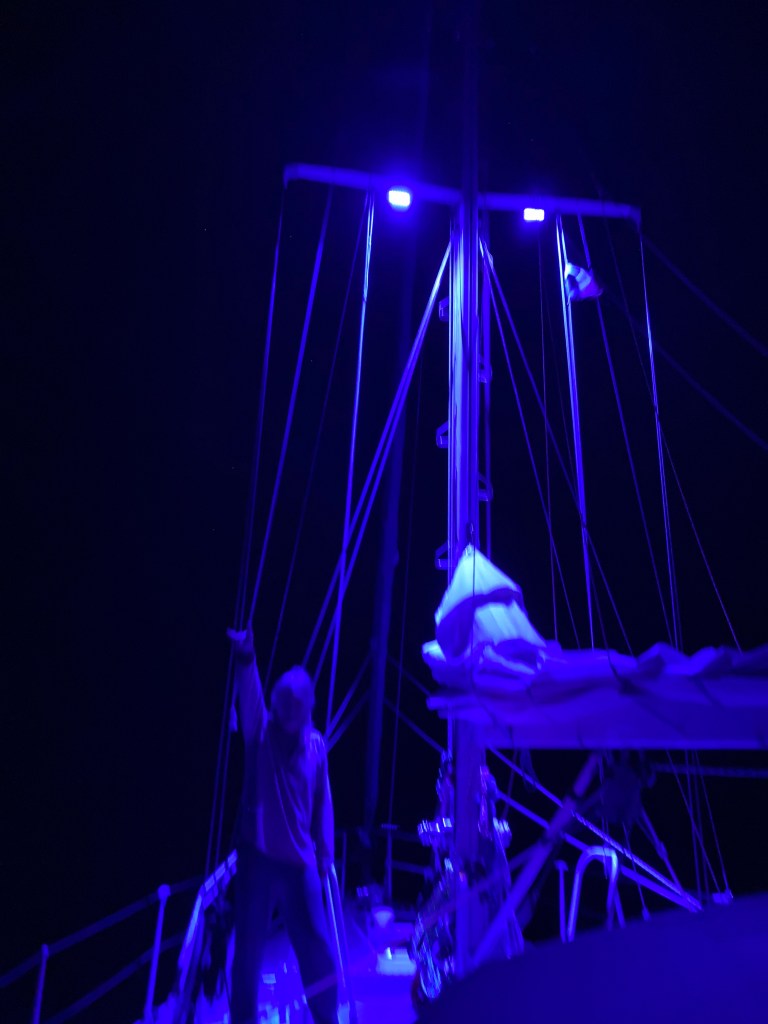

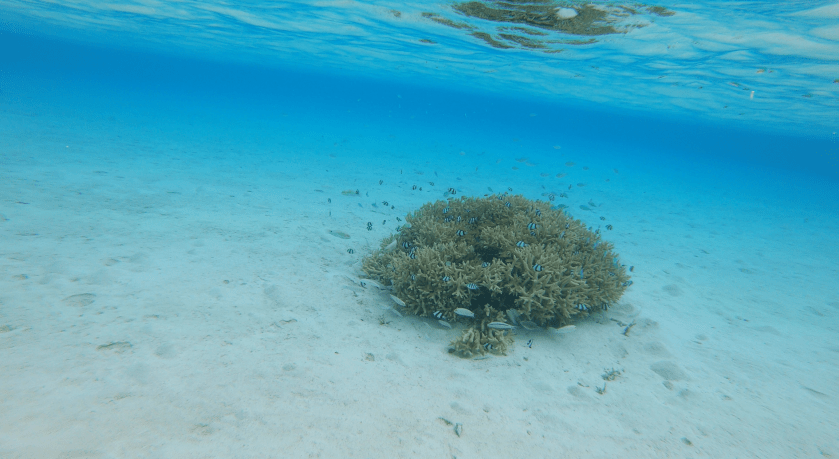

We had been made aware of the fact that a dive shop in town run by a German named Axel had built a great reputation taking divers to what was reported as a spectacular wreck just off the mooring field in town, as well as a night time “disco dive” utilizing UV, or black-light, dive torches to illuminate coral and other marine creatures in a completely unique way. And while I had experienced one of these “glow-in-the-dark” dives once before with a customer I took diving while working at Scuba Junkie which turned out both surreal and stunning, Kris and I were initially content to just do some exploratory dives on our own near the places we had anchored. As it turned out, whether right off of Exit’s transom or via short dinghy rides, we stumbled across some of the best dive sites we had experienced since the Cayman Islands.

Unfortunately, though we had managed to replace our GoPro that had been lost months prior at the end of a dive at Rangaroia in the Tuamotos during which we had seen our first tiger shark (!!!), we had not yet been able to secure an underwater housing, so we were unable to capture any photos or videos during any of the dives… oh well. Back to old school “just having to remember things”.

In Tonga, it seemed we had finally found the elusive paradise that had been hiding from us since commencing on our Pacific Ocean crossing six months prior. Plenty of anchorages; generally, not too many other boats around us; great diving; reasonably calm weather; decent provisioning and supply options; water temperature that didn’t keep us out of the water; and a handful of other sailors whose company we enjoyed.

As it turned out, the couple and crew aboard the sailboat S/V Kahina, who we had gotten to know in French Polynesia after giving them a tow when their dinghy engine was on the fritz (they were also the other two people on our second whale watching tour) had quite a stash of instruments on their boat. One afternoon we had an epic three person jam session while enjoying drinks on a floating bar at the edge of the mooring field in Neiafu.

And then, in the blink of an eye, five weeks had passed and November was upon us.

Tick…tock…tick…tock…

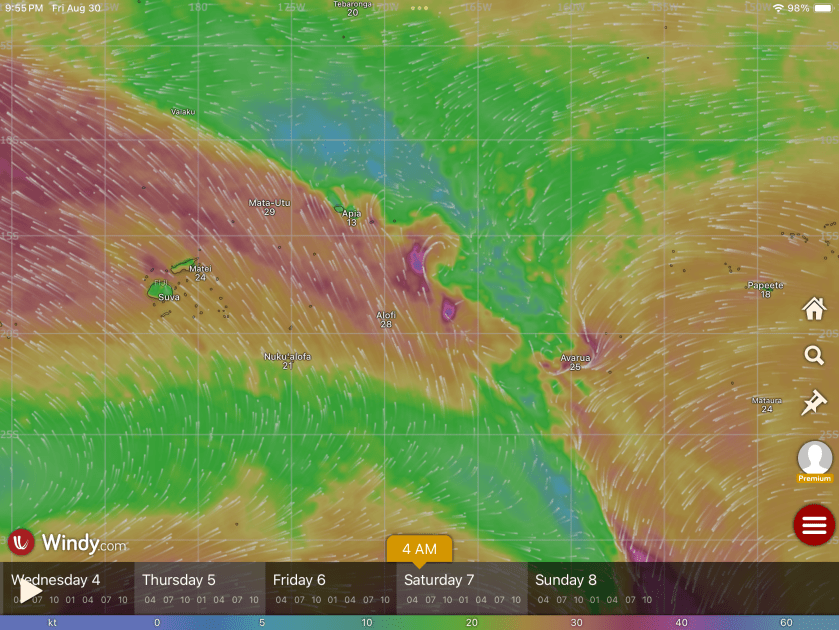

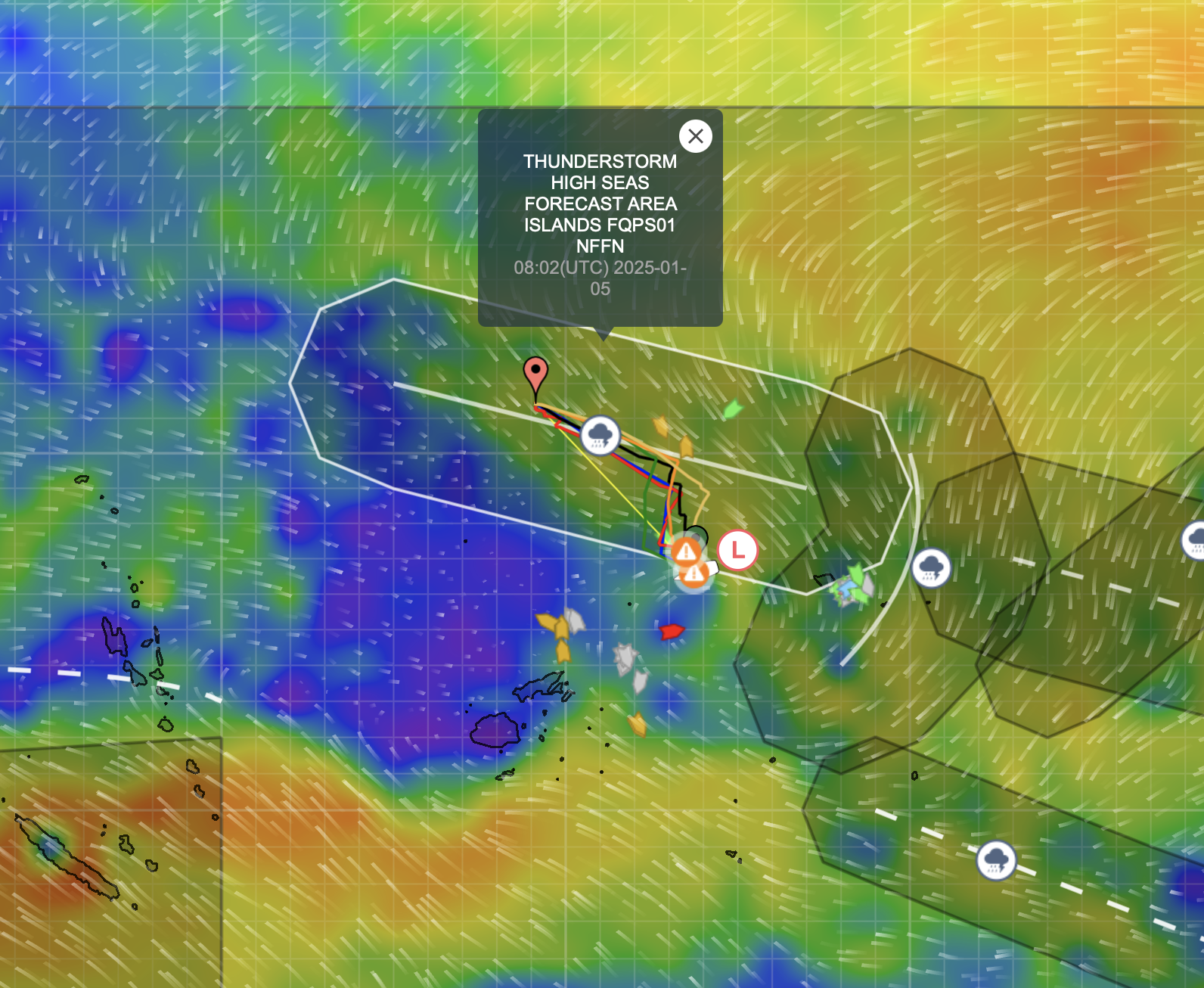

The clock was ticking and we knew it.

We had to finalize our next destination, and soon. New Zealand had been the default choice for months, with Australia being a potential fallback. Unless we could come up with a viable alternative, it looked like we would be endeavoring to sail over fifteen hundred nautical miles with the rest of the herd for cyclone season. Six months. And, to be honest, in the wrong direction. Towards cold water…towards the source of most of the scary weather we had been watching since crossing the Equator…towards all the other boats that made the same herd decision.

Away from SE Asia, which was where we really wanted to be headed. We’d have to make the return trip after cyclone season ended as well.

What were we thinking? There had to be a better option…

And then we spoke to Ben and Sophia aboard S/V Kuaka. They told us they were heading north…