September 21 – October 17, 2025

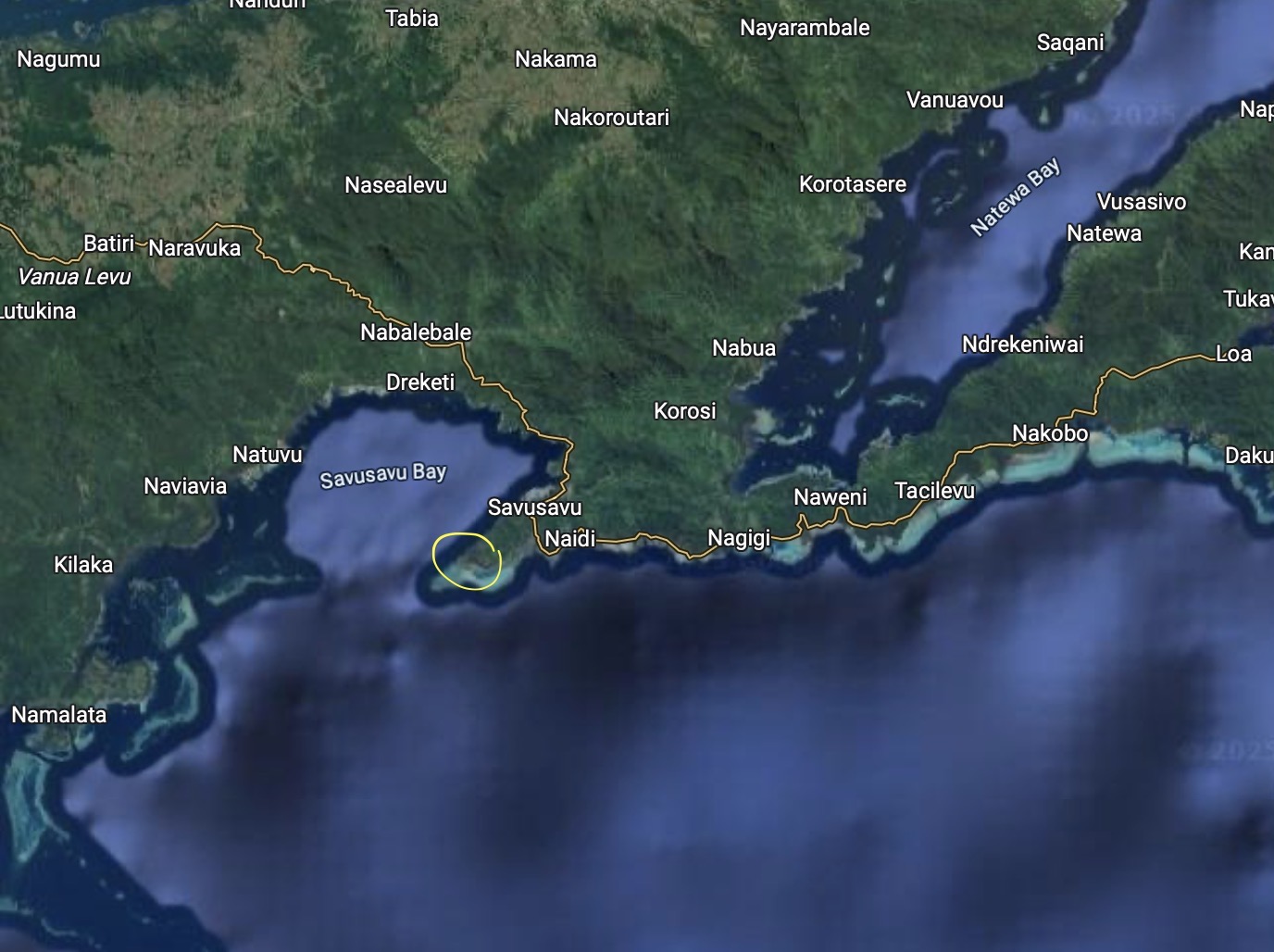

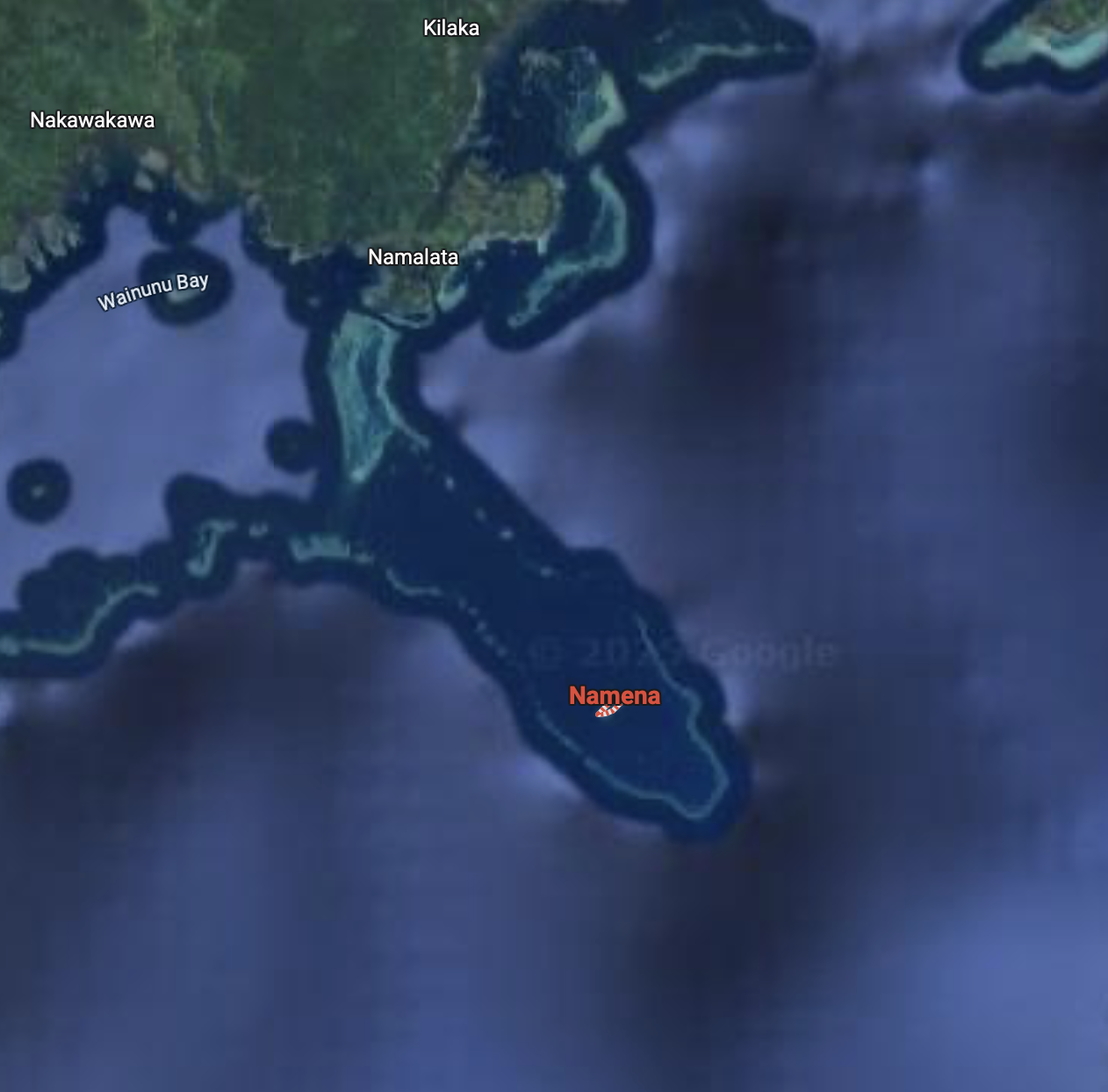

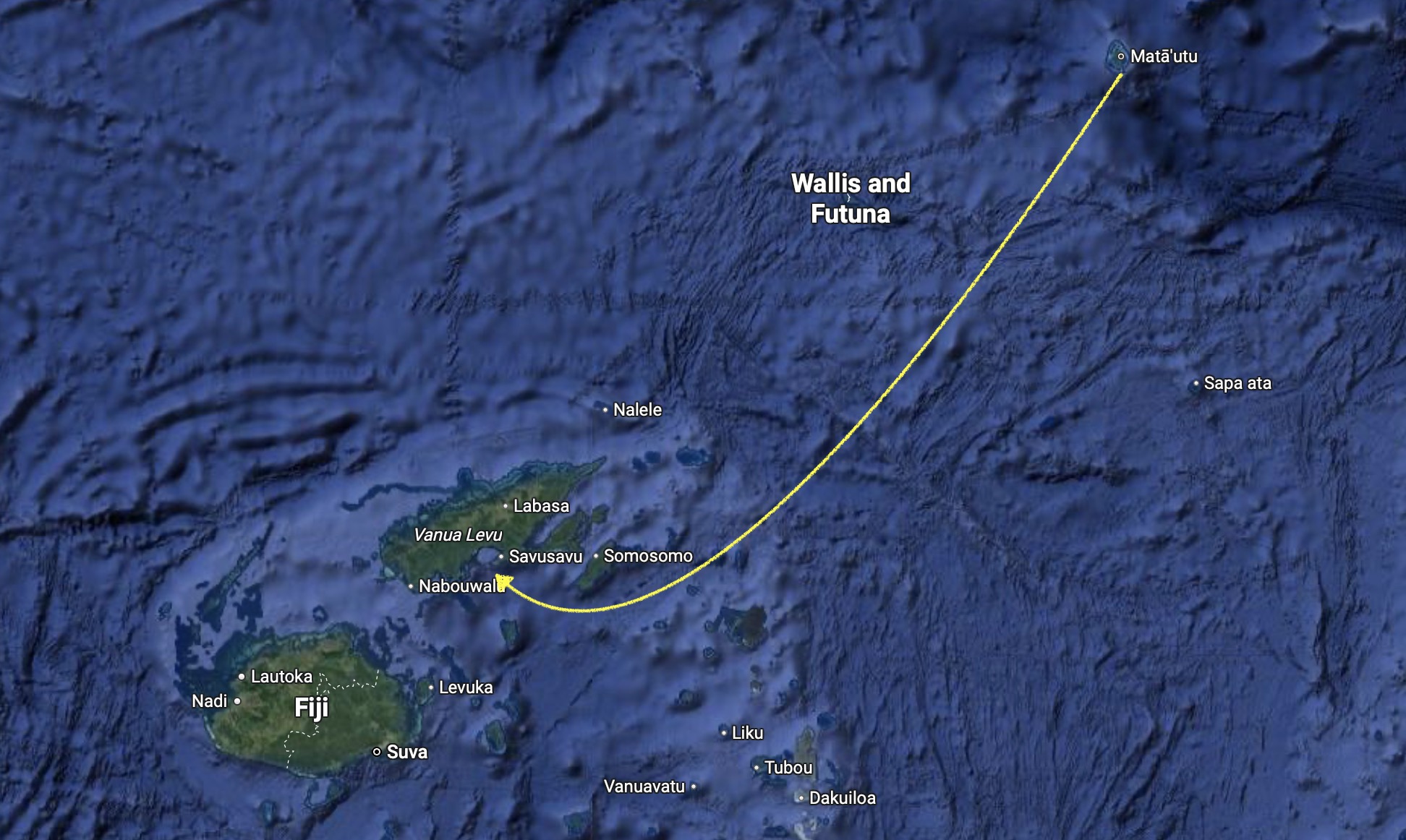

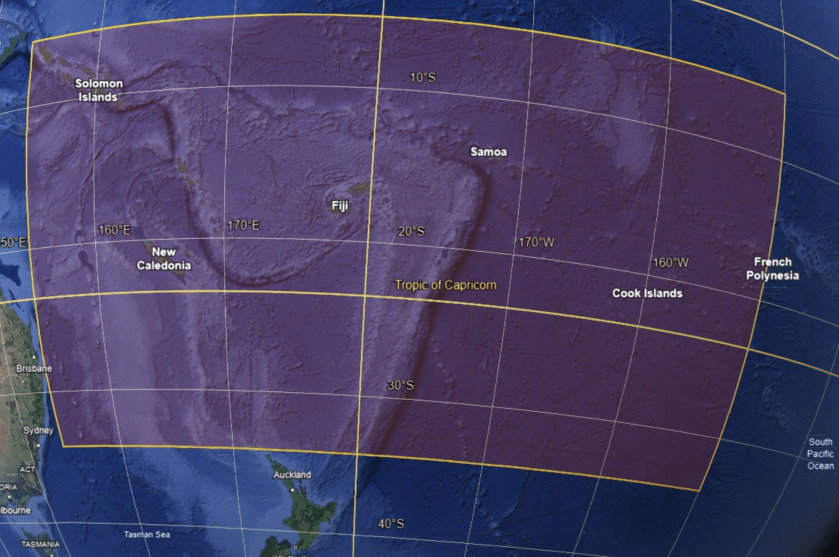

Since first arriving in Fiji in May, we had only explored a remarkably small area. Ninety five nautical miles across and twenty five nautical miles top to bottom. Our own self-imposed Fiji Triangle. A tiny portion of the entire country.

It was now three weeks into September. About nine weeks remained before we would reach the December 1 deadline imposed by our insurance company to be north of 10°S latitude for the cyclone season. A direct sail to the Solomon Islands was only about a week to ten days away…nine hundred nautical miles. However, we hoped to make a detour to Vanuatu along the way. West to Vanuatu would be around eight hundred miles and then another five hundred or so miles to the Solomons. Not that much farther, but it was obviously going take substantially longer if we planned to spend any time enjoying Vanuatu, which would be the entire point of going.

The ticking of the clock hadn’t reached a distracting volume, but it was certainly becoming more noticeable. We weren’t in a hurry, but we needed to get moving.

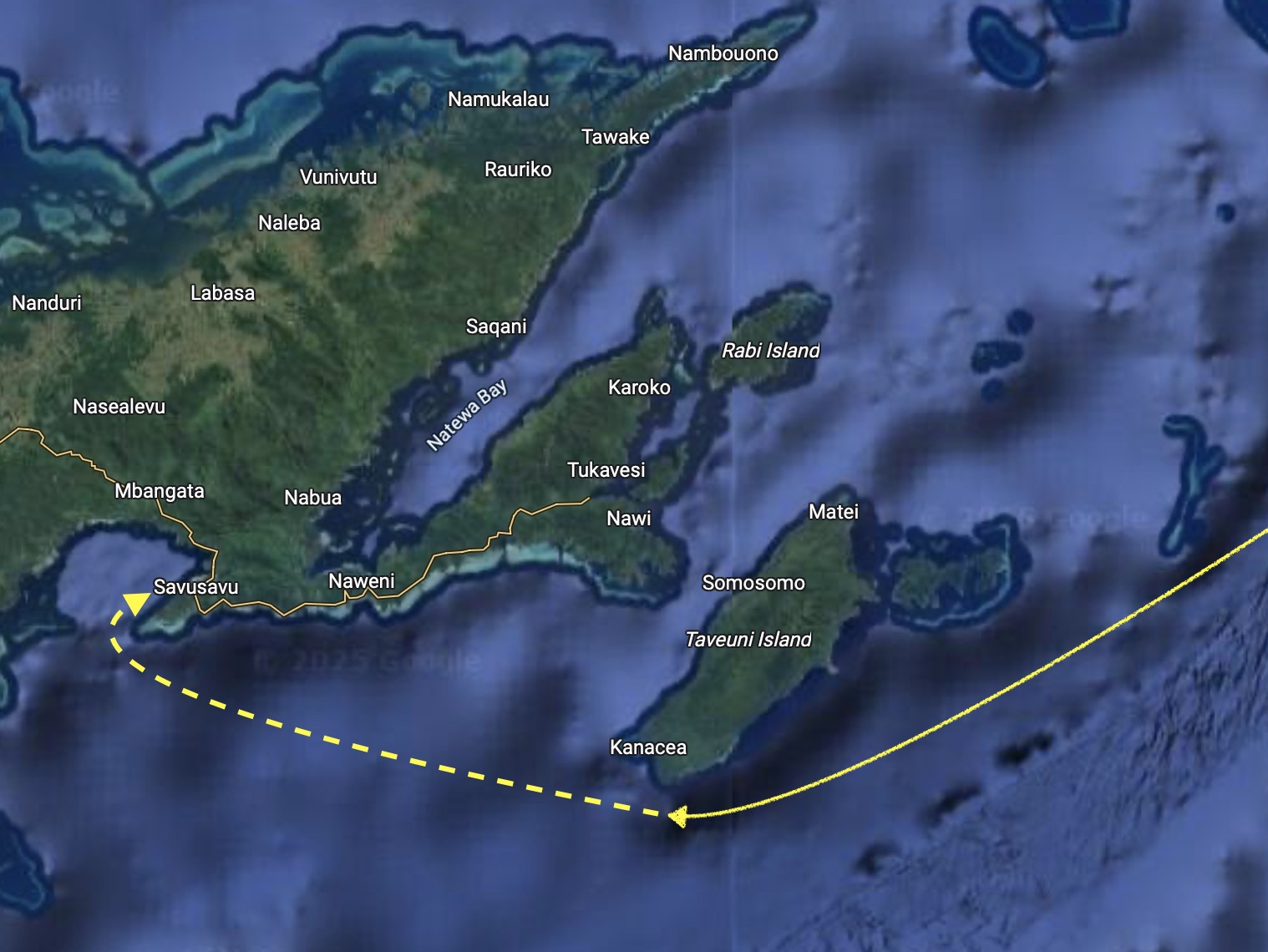

From the mooring ball at Waitui Marina in Savusavu, to Nemena Island, and then Yadua Island, we had sailed around eighty four nautical miles. Already about a quarter of the way around Vanua Levu.

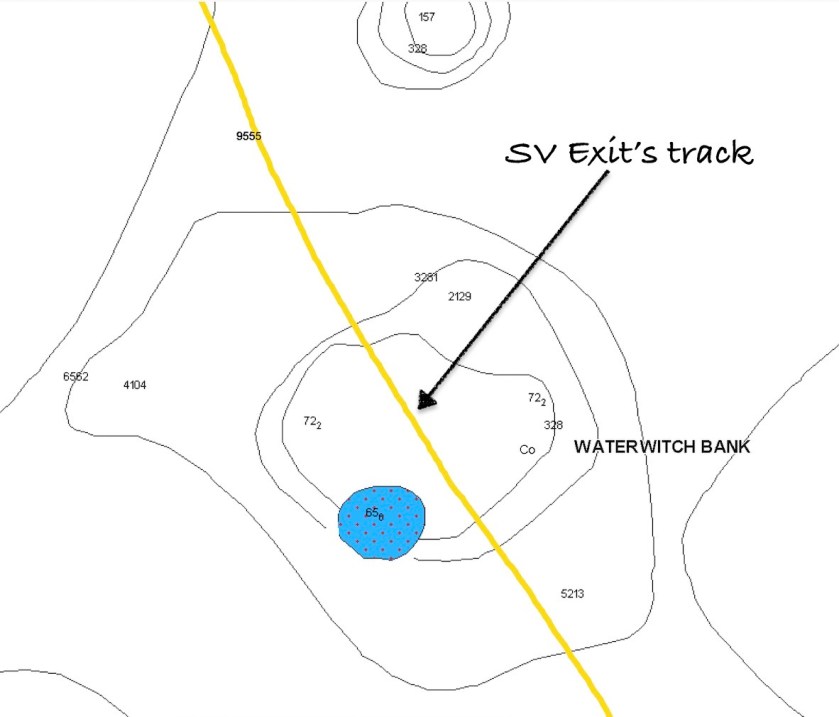

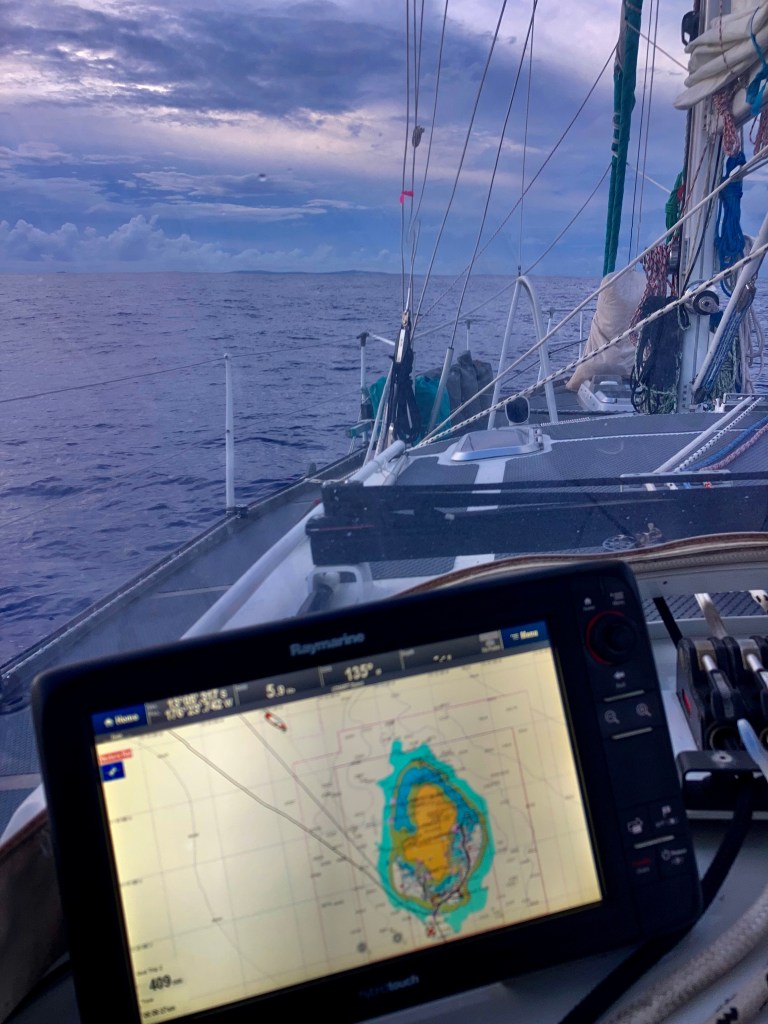

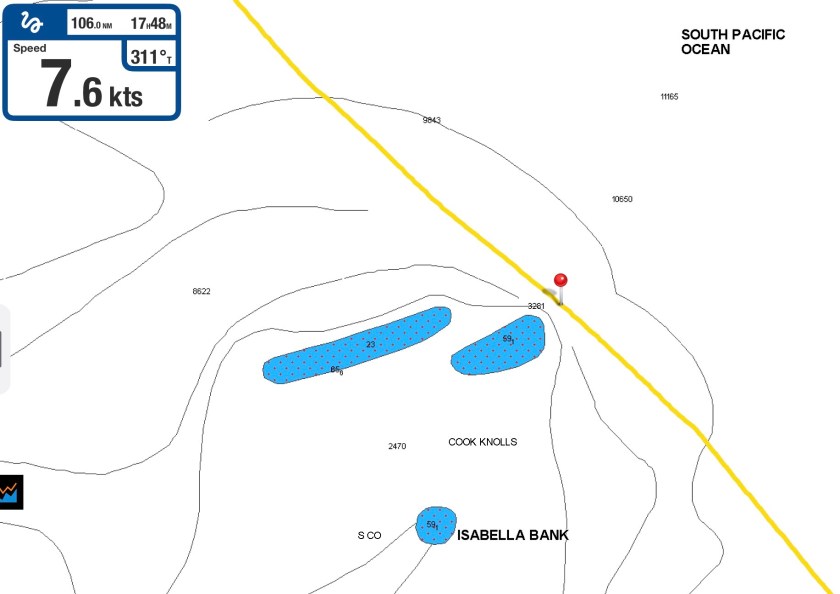

Before departing Yadua Island, we plotted a number of anchorage options into our Navionics electronic chart on the iPad. Nothing was set in stone, but it gave us a sense of distances and options. There were always other possibilities. However, we already knew that some of the chart information would be either inaccurate or incomplete; consequently, we wanted to make sure we were only moving during hours of decent light.

We left Yadua under flat calm conditions. An hour later, by the time we had poked around the east side of the island, we were reminded just how sloppy the Bligh Waters could quickly devolve into.

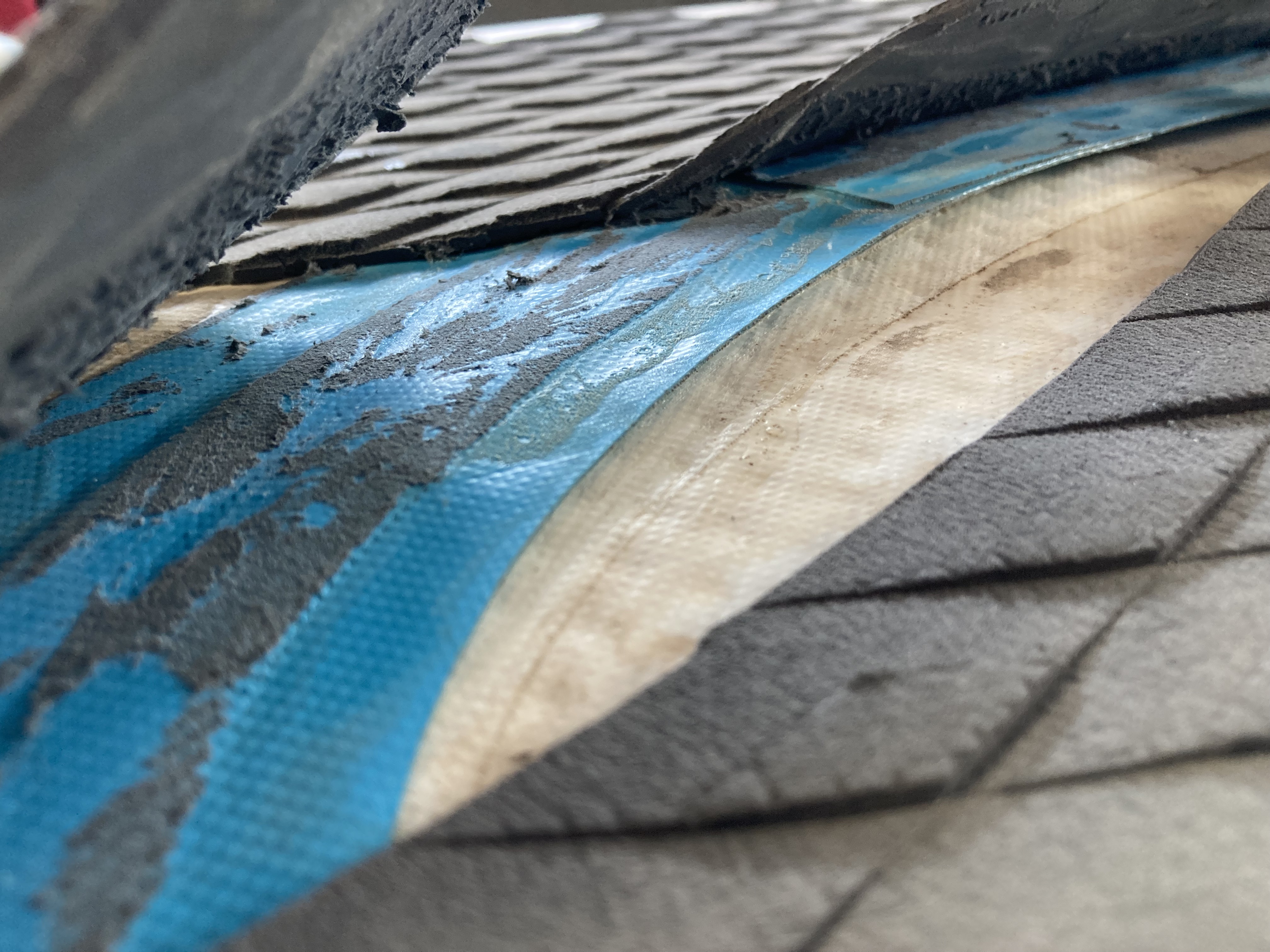

Not really that bad, but we were sure relieved to not be stressing over a leaking rudder seal. That was for damn sure.

Working our way around the northwestern tip of Venua Levu, we enjoyed conditions which permitted us to sail without having to burn diesel. The farther we progressed around the north side of the big island, the more we would learn that wind conducive to sailing could be quite fickle on this side.

Between the uninhabited bay we had anchored in just north of Nokanoka Point on the northwestern tip of Vanua Levu and Uluidawani, another random location just over thirty nautical miles to the east, we saw winds that shifted from dead downwind at four knots to between twenty five and thirty knots directly on our bow.

The forecast had been seven to ten knots on our beam. Instead of a forecast, we began to joke it was a two-cast at best.

Uluidawani turned out to be a calm and peaceful spot for us to drop anchor for the night. Though it was only another ten miles to our intended destination, Nukubati Islands, we had arrived at Ulidawani at just after 4pm. With questionably accurate charts, especially regarding depths near shore, our strategy was always to try to arrive at a potential anchorage with good enough light to be able to see possible hazards lurking near the surface, shallow areas and shoals, as well as what we were dropping the anchor on. Floating the chain always helped, but peace of mind really depended finding a clear spot we had been able to verify with our own eyes.

By the time Exit reached Nukubati Islands and dropped anchor, we had already made contact with the folks at Nukubati Island Resort via email. At the time of our arrival, they had no guests.

As we were becoming more and more aware of, the entire northern coastline of Vanua Levu is rather undeveloped and isolated. Not only were cruising yachts rare in the area, apparently so were tourists in general.

Curiously, Savusavu, whose population was reported as less than 3,500 people in its most recent nearly twenty year old census, is much more of a cultural, tourist, and commercial focal point than nearby Labasa (pronounced Lambasa), the actual administrative hub and largest town in Vanua Levu with a population of 28,000 people – more than eight times the size of Savusavu.

Jenny, one of the owners of Nukubati Island Resort, met us on the beach as we pulled our dinghy out of the water. During our conversation, she revealed that she had been born in Labasa, less than twenty miles away, before adding it was a dirty town she didn’t miss and wouldn’t recommend visiting.

With her Australian husband Peter, Jenny opened Nukubati Island Resort many years ago. Though Jenny and Peter still run the resort, they have begun passing the torch to their daughter Lara and her husband Leone, who run the resort’s dive shop while raising their young child at the resort, who will mark the third generation of the resort’s legacy.

Nukubati Island Resort boasts of being the only resort with direct access to the Great Sea Reef. Not only that, Leone (also born and raised in the area) has achieved a legendary reputation of being one of the most experienced and knowledgeable scuba divers regarding the Great Sea Reef.

Only a month earlier, Leone had been utilized as an expert guide for a research expedition to study the Great Sea Reef and surrounding marine environments aboard the expedition vessel RV Argo.

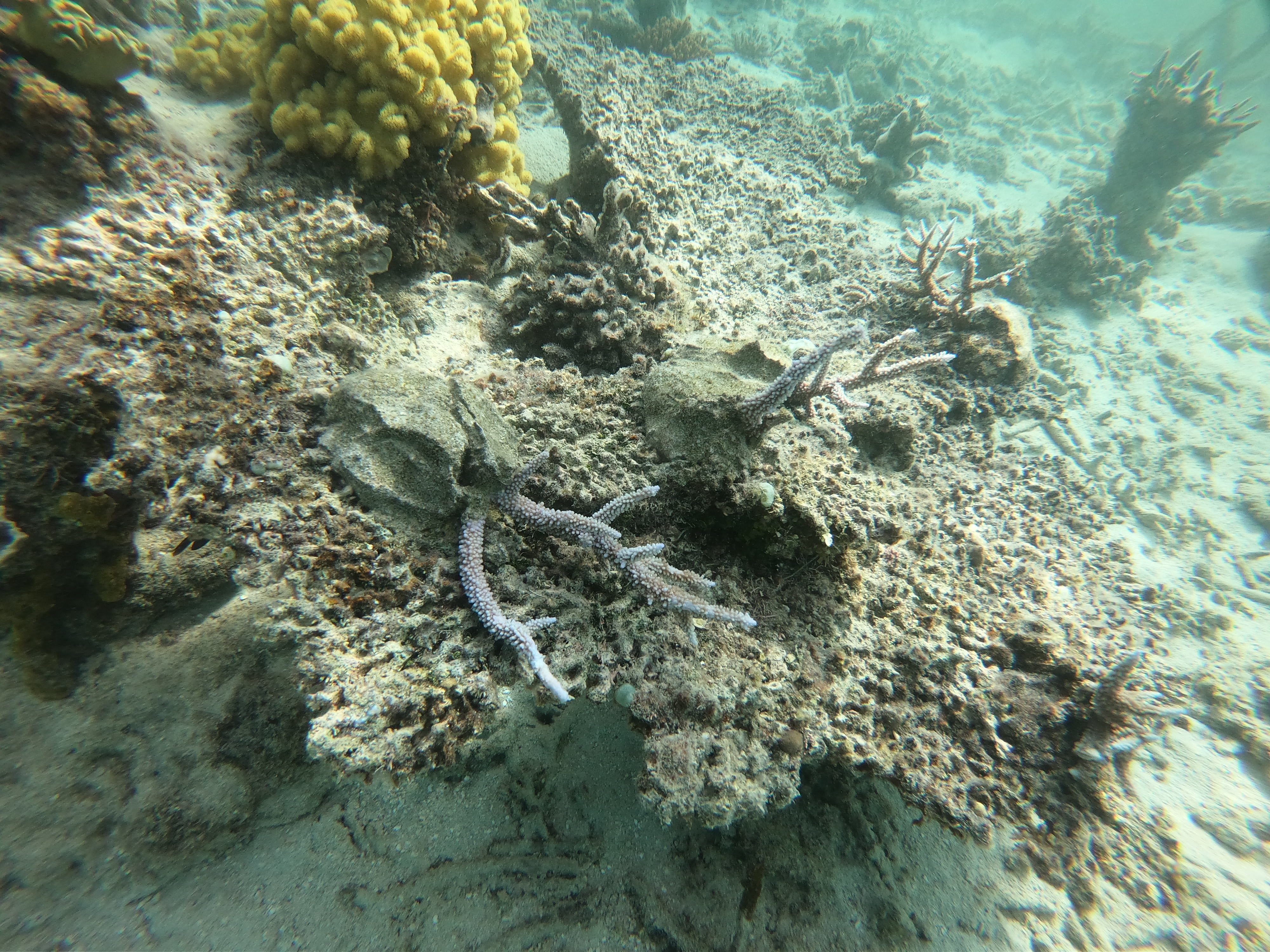

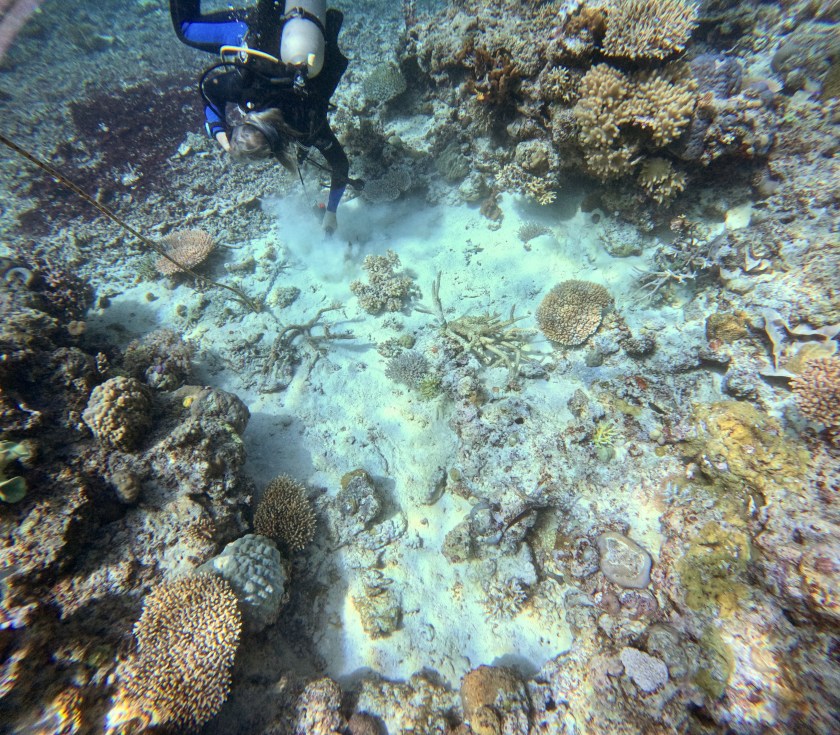

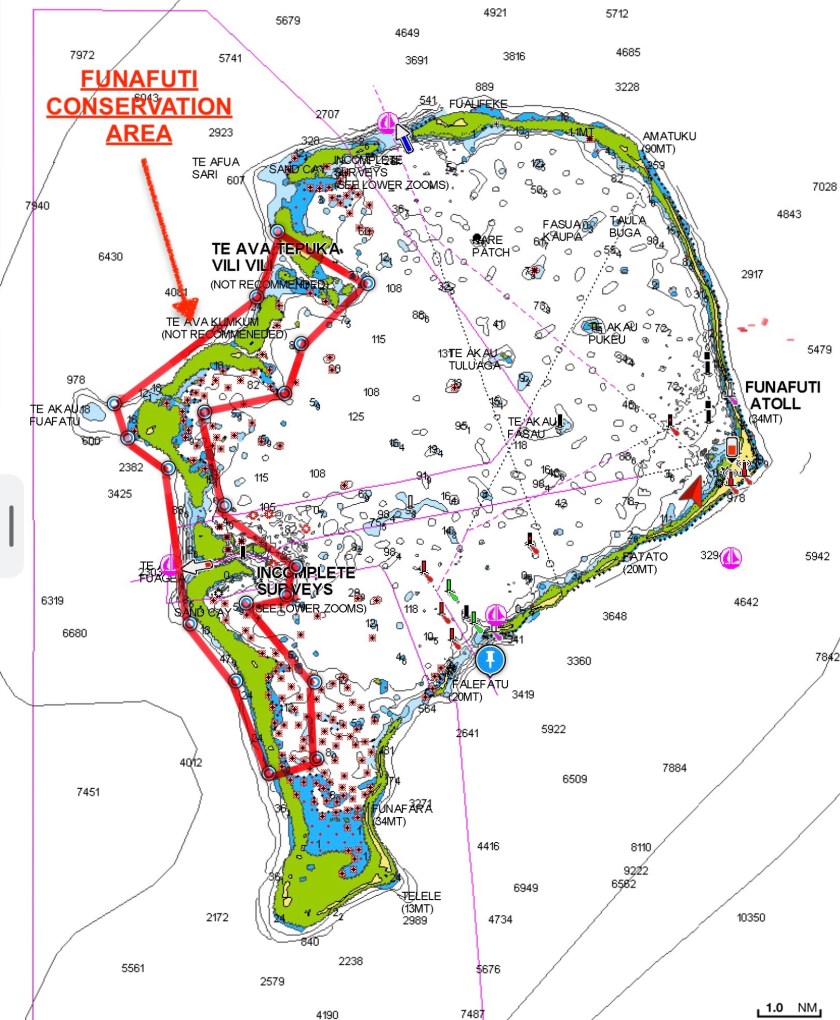

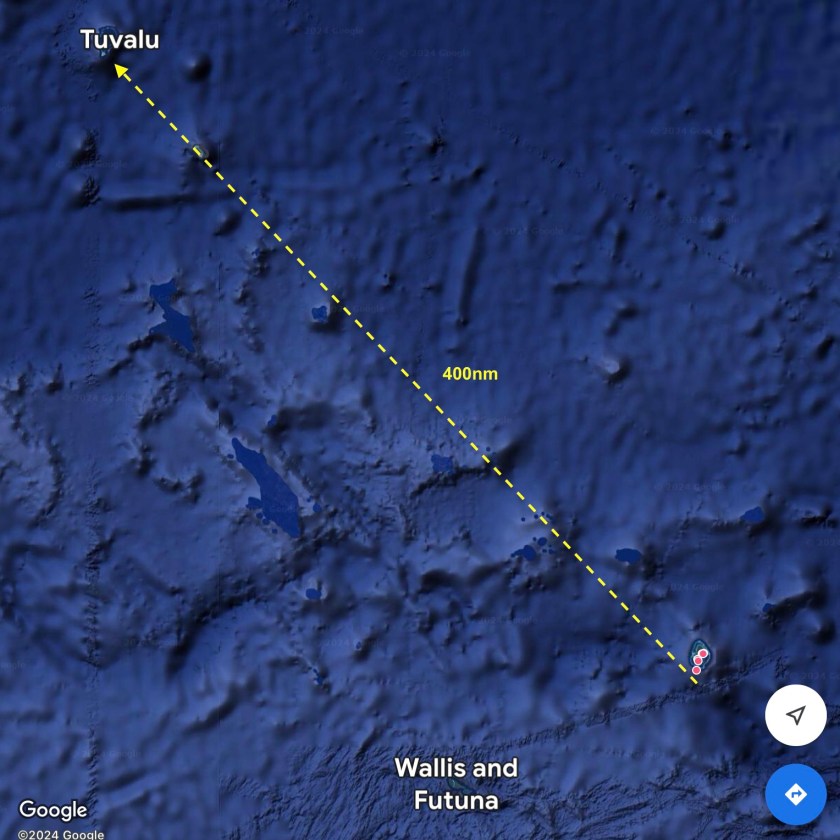

Strangely, we had first learned of the work being done aboard Argo while we were sitting out the cyclone season in Tuvalu, six hundred miles to the north. They were there at the same time, doing research dives on the outer reefs of the atoll. During subsequent conversations with Leone, he conveyed to us just how stunned the research team aboard Argo had been upon witnessing the devastated condition of the coral reefs and marine ecosystem around Tuvalu – something we were already all too familiar with from personal experience.

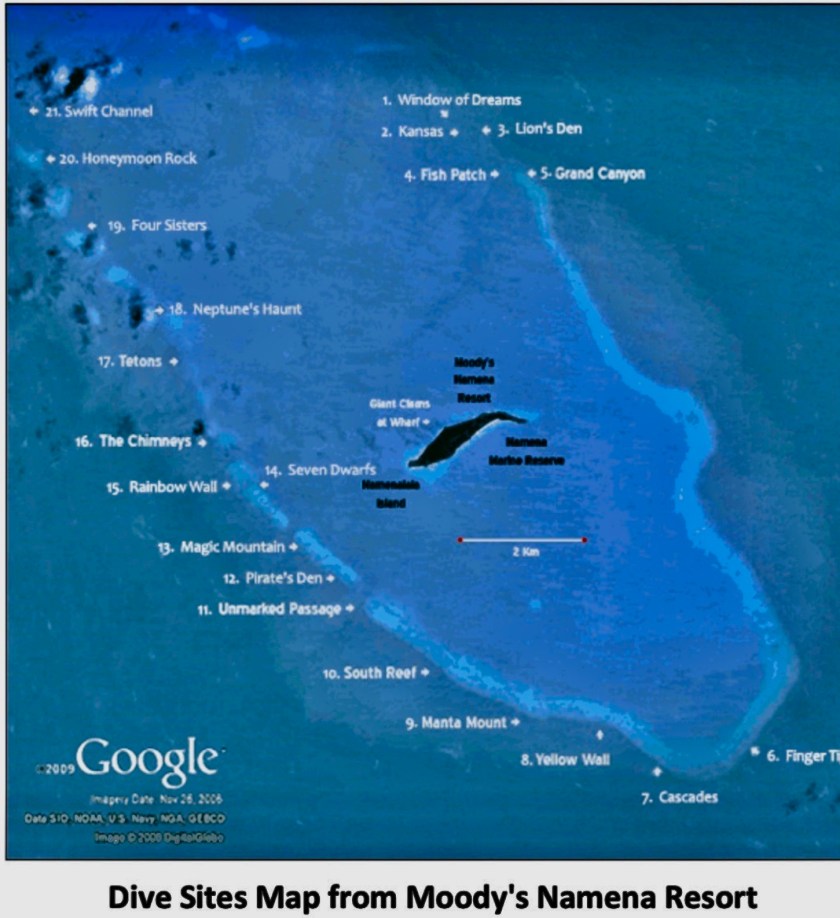

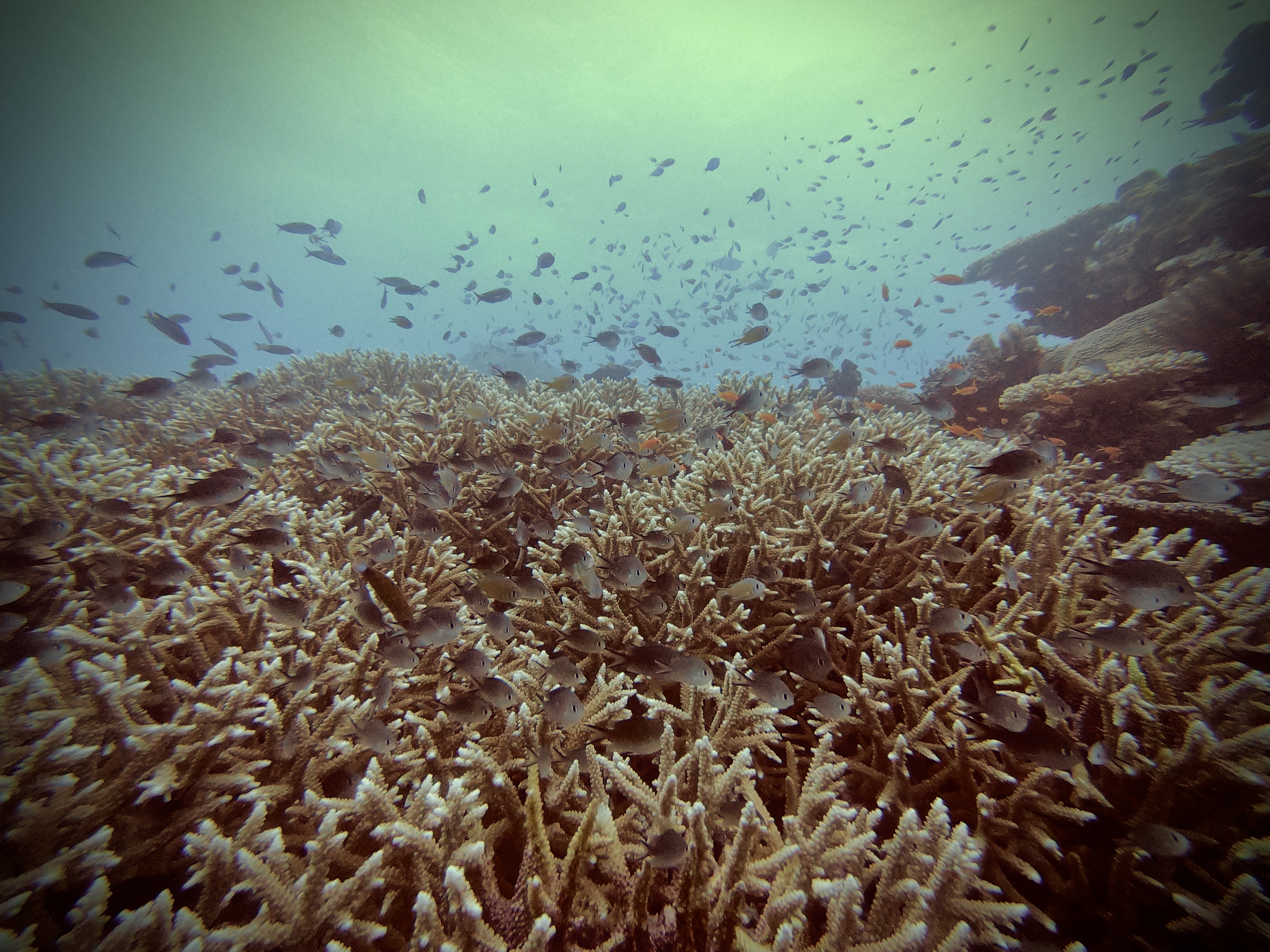

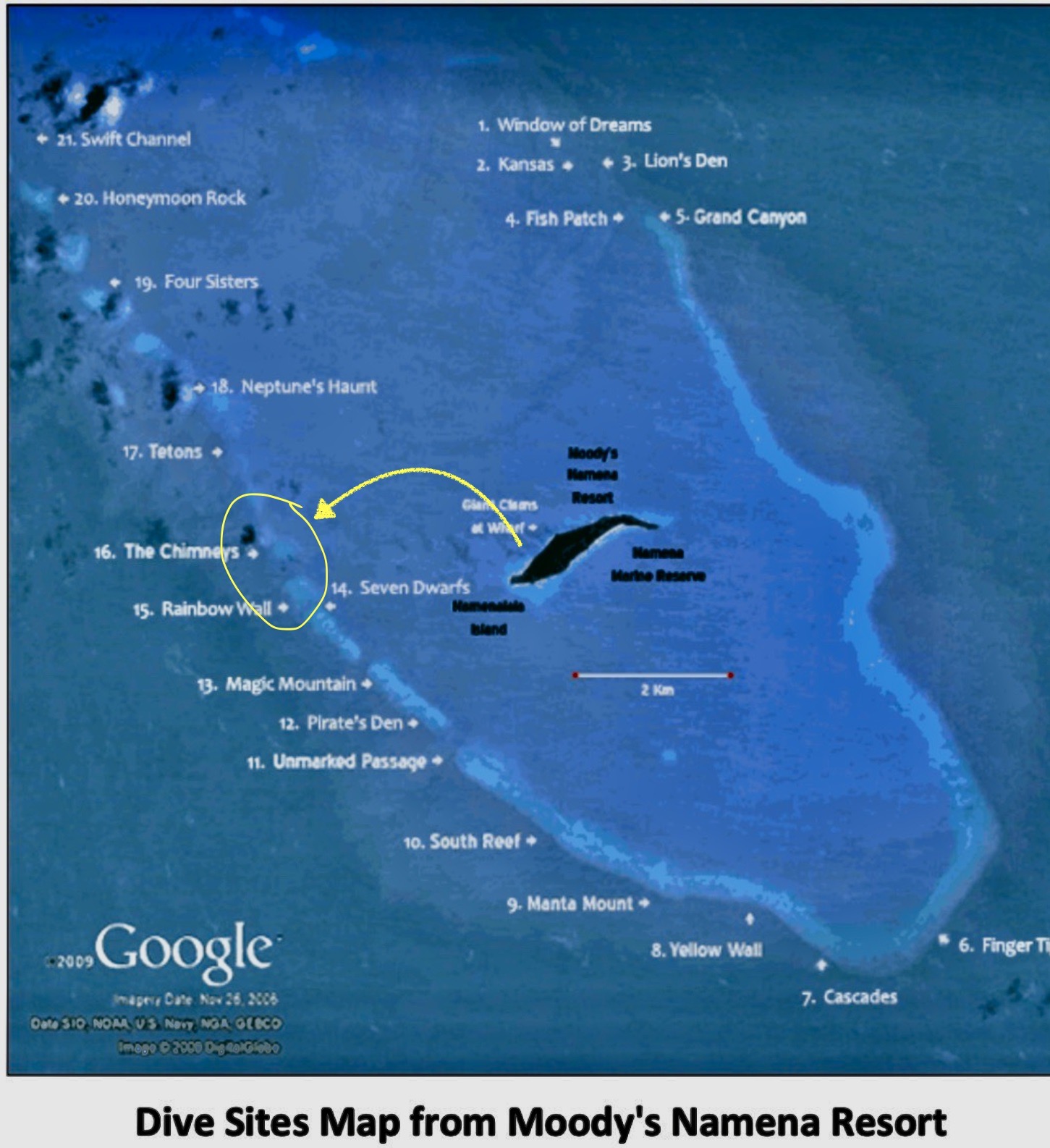

On the other hand, we were currently sitting on the doorstep of the world’s third-longest continuous barrier reef and supposed home to 74% of Fiji’s coral species and 80% of its reef fish. Considering what we had already experienced at Rainbow Reef, Namena Island, and Yadua Island, we were literally salivating to put on tanks and start breathing some bubbles again.

Diving the Great Sea Reef with Nukubati Island Resort

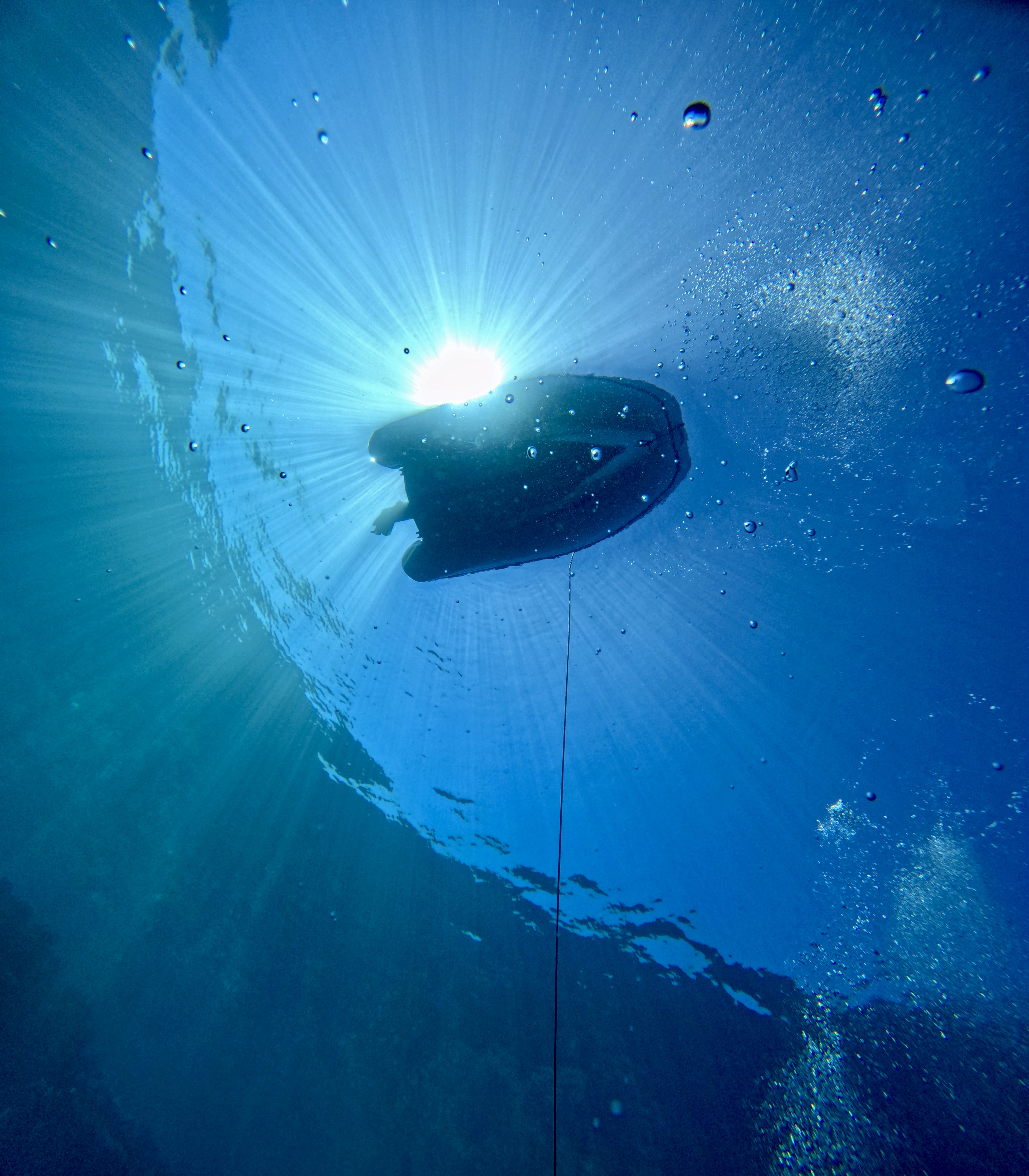

On the morning of September 28, with no one other than the dive staff aboard, we hopped on the resort’s dive boat and headed to the outer side of the reef. After motoring through one of the passes and assessing the conditions as perfect, we donned our scuba gear, took a giant stride off the stern of the boat, and with the area’s most experienced legend Leone Vokai as a personal dive guide, explored the Great Sea Reef.

Absolutely extraordinary. Grey reef sharks; white tip reef sharks; bull sharks; eagle rays; large bull and blue spotted stingrays; octopuses; large barracudas, tuna, and Spanish mackerels swimming above us; endless varieties of brightly colored reef fish; massive expanses of plate coral covering sloping walls that plummeted into the depths, unbelievable fields of incredibly healthy and diverse coral of every type; sheer wall and canyons; staggering clear visibility in water that seemed to contain every shade of blue imaginable.

The water conditions were so good that Leone took us to a sight they had never dived before. He said the location had always intrigued him, but currents and surface conditions in the area had never been favorable to explore it. We jumped at the opportunity and were not disappointed.

He later informed us that, since we were the first to dive the site, it was up to us to name it. Eventually, we settled on a name… EXIT’S SECRET. Evidently, our own legacy on the Great Sea Reef had been established.

We had such a phenomenal time that we returned the following day. Though Leone was unable to guide us on the second day, we were still well taken care of by the same staff we had enjoyed getting to know the day before.

As is so often the case, even having experienced mind-blowing dives, we had to make the hard decision to move on. A finite budget had to be conserved and, despite the fact that September was about to come to an end, we were still less than half way through our circumnavigation of Vanua Levu.

We had hoped to potentially do some dives on our own after gaining local knowledge and information. However, the reality was that the logistics would have been excruciatingly difficult. We concluded it was better to pack away the experience we had just enjoyed as the best we could hope for and be content with that.

After an uneventful stop fifteen or so miles to the west, near an abandoned resort called Palmlea Farms Lodge (apparently currently for sale for anyone in the market for Fiji property), we ushered in the arrival of October sailing another twenty nautical miles to Blackjack Bay.

Although there was no village or houses anywhere nearby that we could see, a lot of local small boat traffic passed by us while Exit sat at anchor in the small bay.

Most of the occupants of the local boats simply smiled and waved enthusiastically as they passed by. A few stopped at the transom of Exit, briefly inquiring where we were from in the most welcoming and friendly manner.

One boat that stopped, filled with a group of women and children, seemed particularly intrigued by our presence. After a few moments of reserved curiosity and tentative looks, we invited them into the cockpit. A barrage of smiles and questions ensued, complete with requests for photos and selfies.

Concluding a brief and truly entertaining exchange, the group climbed back into their small boat. With warm heartfelt smiles and waves, they untied from Exit’s transom, disappearing around the corner of the peninsula as they headed towards their village on the tiny nearby island of Druadrua. Classic.

For as many cheerful and benevolent exchanges as we have, inevitably there’s gonna be a few duds. The only real uncomfortable moment occurred when a local boat filled with ten or so people stopped and identified themselves as either Mormons or Jehovah’s Witnesses. In short order, it seemed to us that they were making references to sevusevu (the gift presented requesting permission to remain as visitors). When we happily offered a bundle of kava, the ginormously overweight guy who identified himself as the pastor frowned and informed us that they did not drink kava…nor did they drink alcohol…nor did they smoke. After a number of questions including asking what we did for money and why we did not have any children, he asked if we had any Tylenol for the pain he was experiencing (obviously from carrying around three hundred or so pounds of extra flesh) for which we gave him an entire bottle of Ibuprofen. His demeanor seemed lukewarm warm, at best, to the idea of accepting a bag of rice we had offered them. Finally, they seemed done with the exchange and continued on their way. Awkward…to say the least. The righteous and religious can be so fucking weird.

After a few lazy days, which included quietly celebrating the forty-third (:-o) anniversary of our first date together, as well as the seventeenth anniversary of our departure from the USofA (both falling on October 2), we picked up anchor and continued another twenty six nautical miles to another uninhabited speck of mostly mangroves, Tilagica Island.

The following day started before sunrise. It was a big day. Halfway through the nearly fifty nautical mile journey that was in store for us, the northeastern trajectory we had been following for the past two weeks would shift to due south. Today we were rounding the northeastern tip of Vanua Levu making for Albert Cove on Rabi (pronounced “Rambi”) Island.

The upside was it was a gorgeous day. Clear bright blue skies with matching clear electric blue seas. The downside? No wind at all. It would be eight hours straight of motoring.

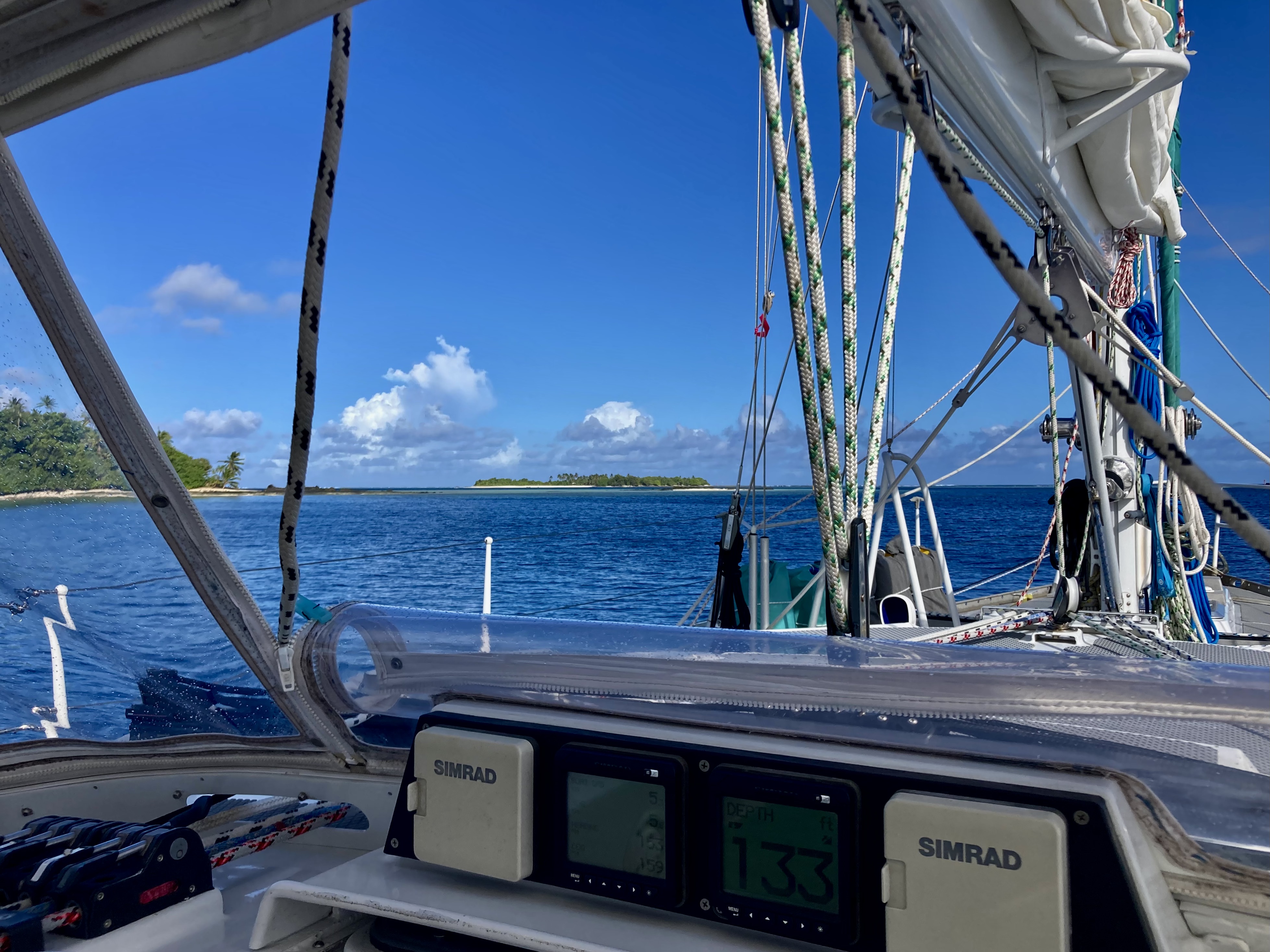

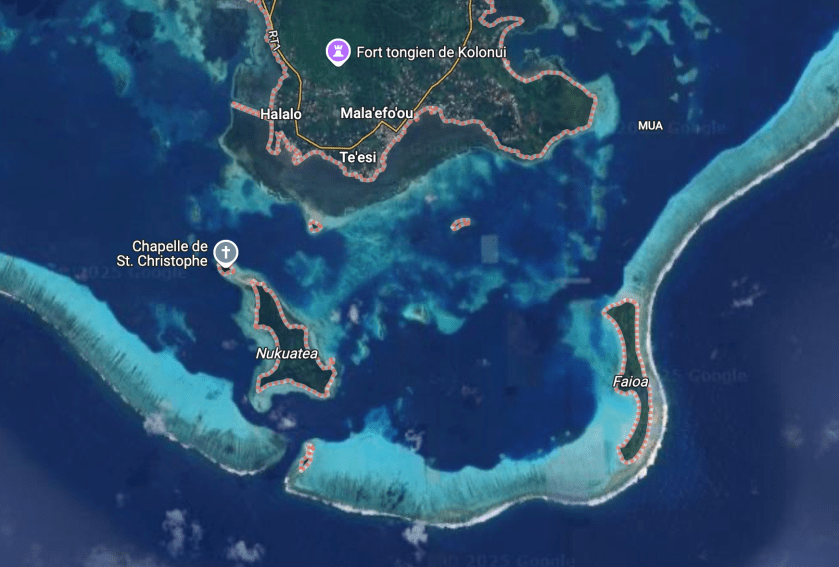

Albert Bay turned out to be a postcard perfect location. The bay is nestled on the northern side of Rabi Island, between a sandy beach and a massive reef just offshore with only a narrow channel for access into it.

Some areas of the reef are rocky. Others are covered with impressive and very photogenic coral colonies.

The unfortunate reality of Rabi island is the history of its current five thousand inhabitants. They are not actually Fijian, but rather the descendants of the Banabans, the original indigenous landowners of Ocean Island, in the Gilbert Islands over twelve hundred miles away.

A depressing story that perfectly encapsulates the fucked up nature in which indigenous people so often get shafted by the “civilized people of our planet”. In a nutshell…

During 1941, after ravaging Ocean Island with the devastating process of phosphate mining in support of WW2 efforts, Great Britain (colonial rulers of the Gilbert Islands) decided to resettle the island’s existing population. Incomprehensibly, they decided that the best solution was to purchase Rabi Island (in Fiji) for £25,000 from an Australian firm (that had a plantation on Rabi and somehow owned the island) so they could ship them there. After WW2 ended, and all of Rabi’s existing population were themselves relocated to Taveuni Island to the south, most of Ocean Islands population was moved. Among the even more fucked up details…the original group of barely alive Banabans sent there (some 400 adults and 300 children) who had been collected from Japanese internment camps were not given the option of even returning to Ocean Island on the false pretense that Japanese troops had destroyed their homes; the refugees were dropped at Rabi Island in the middle of cyclone season with nothing more than tents and two months worth of food (despite being told houses had already been constructed for them); and even worse, it eventually was uncovered that the £25,000 Great Britain paid to the Australian firm had actually been taken from reparations due to the Banabans for the damage caused by the phosphate mining.

Corporate and political profits at the expense of moral bankruptcy…the way of a civilized and developed world.

Apparently the Banaban citizens of Rabi currently exist in some kind of gray area, simultaneously holding both Fijian citizenship and Kiribati passports with some degree of political and legal autonomy.

Whatever foggy definitions of authority they fall under, whoever is in charge of policing the area proved to us to have their own challenges regarding basic maritime competence.

Less than twenty-four hours after dropping anchor, we watched a local boat that appeared to be an official patrol boat of some sort motor through the pass and into the bay. After dropping anchor along the edge of the inner reef, the boat’s two occupants waded ashore and disappeared into the trees. There were a couple of people on the beach who seemed to make no effort to engage them.

Less than a half hour later, we noticed the still unoccupied patrol boat start to drift towards us. Evidently, the anchor had not been properly secured, and the boat had freed itself with the rising tide as the wind started picking up. It was currently headed for the rocks of the outer reef. As it drifted past us, the two patrol guys appeared on the beach. They looked visibly confused.

Our dinghy was already down. The guys had started wading out into the water, despite there being no way they could possibly chase down their boat. There was almost a thousand feet between us and them. By comparison, there was only about three hundred feet between us and the reef their boat was drifting towards, with their boat splitting the distance right in between. The wind continued to pick up.

Instead of attempting to go get the two idiots wading through the water, I hopped in our dinghy and headed straight for their boat. By the time I reached their boat and got tied off to it, we were only about thirty feet from the reef. The rocks could clearly be seen right at the surface. I gunned the outboard, struggling to control the dinghy which was now attached to a heavy fiberglass boats nearly three times its own size.

Somewhere between comical and super sketchy.

Kris, who immediately regretted not jumping in the dinghy with me, managed to capture a few photos of the whole debacle. Eventually, with the patrol boat serpentining wildly back and forth and me desperately trying to keep from getting the lines caught in our outboard’s propeller, I was able to slowly tow the patrol boat back to the two guys, who by this time were standing at the outer edge of the reef just off the beach, trying not to look as stupid as they must have felt. They did thank me, though when they passed by us on their way out of the bay, it appeared that they had both made a very conscious effort to not look over our way. Funny how embarrassment and humiliation can make even authority figures try to be invisible.

If you are fortunate, goodwill can sometimes be a two way street and positive karma can bounce right back almost instantly.

Not only had we been in the right place at the right time to help out the patrol guys who had misplaced their patrol boat…we also were more than happy to oblige a young man who paddled up in his plastic kayak over a number of days and requested we charge his phone during the day.

We expected nothing in return, but were more than happy to accept a bundle of fresh and delicious lettuce from his garden when he came out to pick up his phone at the end of the day. Sweet.

Beyond the patrol boat drama and daily visit from our new friend with the depleted battery cell phone, it was a relaxing and unremarkable few days.

On the south side of Rabi Island, we found a small nook to drop anchor in. As it turned out, not the best anchorage – a deep and narrow area that our anchor had trouble setting well in, plus we ended up with the anchor getting hung up on something at the bottom. In addition, a never-ending parade of trucks, seemingly affiliated with some kind of a nearby biofuel station, passed back and forth on a tiny road hidden just behind the trees creating a continuous background hum. Oh well. Every stop can’t be a gem.

Departing Rabi Island, instead of returning to Viani Bay where we had dived with Dive Academy three months earlier, we chose to duck into a small bay just to the north called Naqajqai Bay.

Great holding. Protected. Quiet. Beautiful.

And yet…

We’re on a boat for fucks sake. Living the dream is a phrase uttered by spiteful dirt dwellers and gloating boat owners who only spend only a fraction of the year afloat. Without having an inkling of regret, in reality the fact is when you live on the ocean 24/7, one of life’s cockroaches is always lurking somewhere in the cracks.

As we prepared to leave, while picking up anchor, I noticed our windlass began having a great deal of trouble bringing up the chain. When the anchor appeared at the surface, lo and behold, it became obvious why. We had snagged what seemed to be a hose of some sort. Or holy shit…it occurred to me we may have actually hauled up a power cable. Yikes!

With a great deal of apprehension and care – the kind you tap into when you want to avoid either electrocuting yourself or causing a power blackout for an as of yet undetermined area of Fiji – I grabbed one of our boat hooks and very gingerly hooked onto the line. Then, as I lowered the anchor slightly, Kris reversed Exit a few feet and I released the line. Fortunately, whatever it was slowly sank and disappeared back into the depths.

Sometimes it’s just best not to dwell on what could have but didn’t actually come to pass. It was a relief to start breathing again.

Having escaped Naqajqai Bay without requiring the assistance of either the Fiji Power Company or a defibrillator, we headed for our last destination before returning to Savusavu – Taveuni Island.

We had passed by Taveuni Island both upon first arriving in Fiji as well as when we were sailing from Namena Island to Vianni Bay to dive the Rainbow Reef, but we had never stopped there.

Now we planned on picking up a mooring ball at Paradise Taveuni Resort, which we had heard was very cruiser friendly.

About halfway there we were ecstatic to see a pod of dolphins approaching Exit. As it turned out, we were in for an even bigger treat.

The dolphins were actually escorting a pod of what appeared to be over a dozen pilot whales! We had seen pilot whales briefly before from Exit’s deck, but only from a distance. This time, we were able to shut off the engine and drift, where they cautiously approached us. As we lowered the GoPro into the water, we discovered even a grey reef shark (either an odd friend or a nefarious stalker hoping for a young pilot whale snack) swimming below alongside the group.

The water was so calm and clear that the visibility was amazing. At times, it was like looking through a window at them. Absolutely unbelievable!

Eventually, they decided they had other business to attend to and slowly swam away.

For us, it was one of those highlights you never can anticipate that, in the end, exceeds any experience you can even hope for with a paid tour.

We arrived at Paradise Taveuni Resort and secured Exit to a mooring ball, still wearing ear to ear grins on our faces.

Though we didn’t do any diving with Paradise Resort, we thoroughly enjoyed our time there. The restaurant was excellent, the drinks were inexpensive, and at times we seemed to be quite the celebrities with a group of Americans who had come to Fiji as a dive club and were staying at the resort. As is often the case, they vacillated between outright fascination or admiration that we had sailed all the way here and not quite being able to wrap their heads around the whole concept of living on a boat.

Those conversations can be either very entertaining or painful…or both.

One individual was completely enthralled to have a conversation with us after confessing he had spent years dreaming of doing exactly what we were doing. With a great deal of emotion, he informed us that his mother had grown very ill, and he had watched that dream evaporate after he chose to take long-term care of her instead.

Others peppered us with more typical questions. “What’s the worst weather you’ve ever experienced?” “Do you worry about pirates?” “Have you ever feared for your life at sea?” “How long did it take to get here?” “Where are you going next?” “Do you have kids?” “Are you rich?”

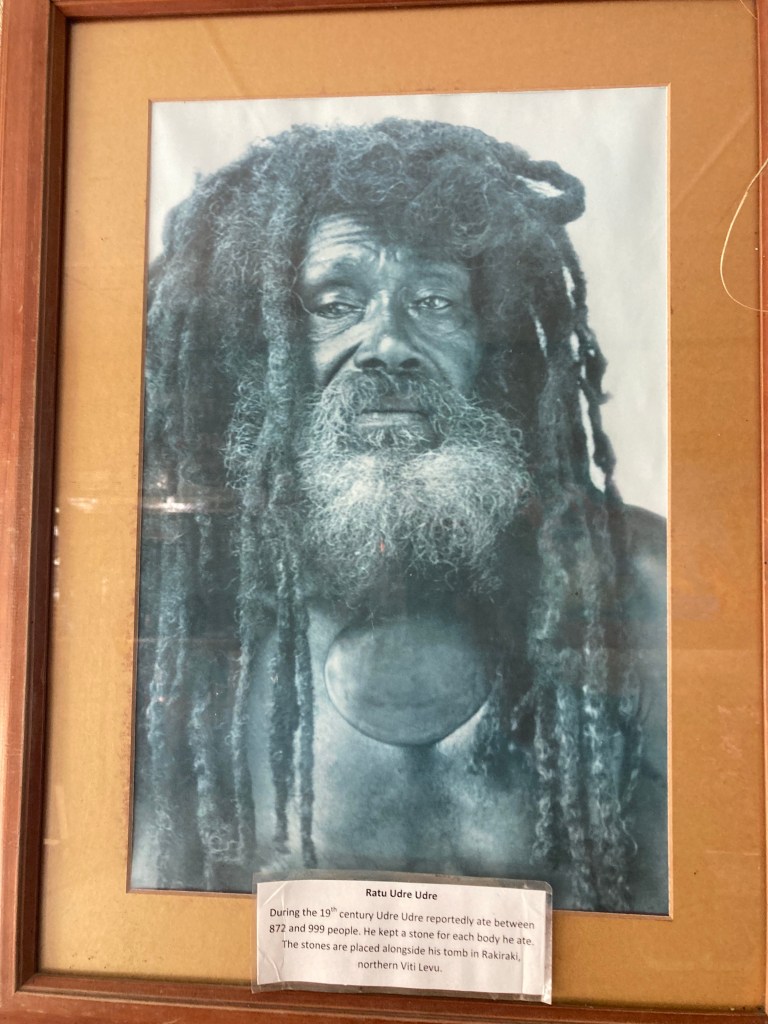

On the wall of the resort were two beguiling photos. One of a 19th century Fijian chief named Ratu Udre Udre, who reportedly ate between 872 and 999 people. Apparently he kept a stone for each body which still reside alongside his tomb on the island of Viti Levu. The second photo was labeled as Lutuna Soba Soba, an ancestor God who is credited with leading his people across the seas to the newly discovered Fiji in the 1800’s. It says his necklace in the photo is made out of Sperm Whale teeth.

Next to the photos were a handful of other captivating tidbits that, based upon the “Exit” sign at the bottom, seemed to speak directly to us – a local artist’s rendition of what appeared to be a traditional Fijian sailing canoe; a profound quote from Jacques Yves Cousteau which said “The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in a net of wonder forever“; and slightly less poetic though no less profound words of wisdom to live by: If life hands you lemons grab the salt and tequila.

True dat.

Without having to pay a nightly rate for a private bungalow, we had the privilege of being able to reap the benefits offered by the resort, while remaining only a two minute dinghy ride from our home at the end of the day.

As a strange twist, we particularly enjoyed the dive shop’s equipment dunk tank…someone had the brilliant idea of designing it as a huge kava bowl. Awesome.

Just like our experience at Dive Academy in Vianni Bay, once again we were able to partake when the resort hosted a lovo, the traditional Fijian barbecue where various meats and vegetables are slow-cooked over hot stones for hours using an underground earth oven. Yum!

In the evening, our view of the sunset over Fiji was completely unobstructed. Oddly enough, for us, another sailboat infringing on our view can be a point of contention.

For many of the resort’s paying customers, their sunset photos had a sailboat in the foreground…us. Ironically, I’d like to think that it added to the ambience of the moment for them. Hmmm.

Sadly, after four days, it was time to get moving. September was more than half over.

After an eight hour sail, we found ourselves once again back in Savusavu.

We had been gone almost six weeks. Twelve anchorages and three hundred forty nautical miles to circumnavigate Vanua Levu.

It turned out our closest call would be on the Waitui Marina mooring ball after returning to Savusavu. A ninety foot aluminium sailboat moored right next to us just about knocked our dinghy Bart off the stern davit when it randomly swung opposite us. Missed us by only about a foot.

Not necessarily their fault…but we had already had a bad experience with these guys less than a week earlier when they arrived at a mooring next us at Paradise Resort, only to learn they hadn’t cleared into the country yet and just wanted to rest using the cheeky excuse they were having engine trouble.

From a customs standpoint…a big no-no that can potentially get you thrown out of the country if you get caught. Assholes.

We laugh that it is only fitting that cruisers who bend the rules with fake excuses of engine trouble get slapped in the balls by Karma when the problem really occurs as a reward for their dishonesty.

We spent the next nine days prepping Exit for an offshore passage, enjoying restaurant food and bar drinks, as well as provisioning as we always do – as though the Apocalypse is arriving.

This included a final visit to the Nawi Marina Bar for Kris’ birthday. Great food, cold beer, and a surprise cake compliments of the kitchen staff. The bartender even informed us of a new drink being offered on the menu…a Perfect Storm – Kraken Black Spiced rum with ginger beer, named in Exit’s honor. Wow!

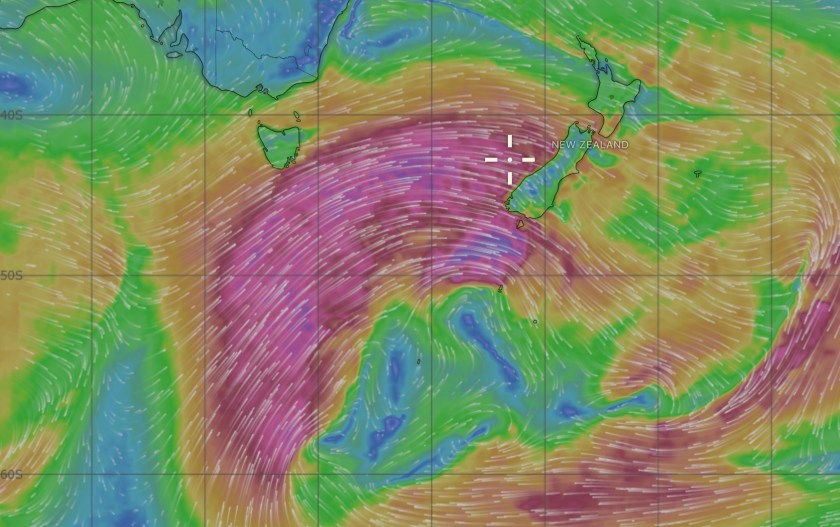

With November just around the corner, we had over seven hundred nautical miles to sail in order to reach our next destination…Vanuatu.

On October 27, the day after Kris’ birthday, we visited both the customs and immigration offices first thing in the morning. By 10am, we had stowed the outboard engine and secured the dinghy. Fifteen minutes later, we freed the lines from our mooring and set off.

We expected to be at sea for about a week.

Maybe a bit more…maybe a bit less. Really, it didn’t matter.

Exit was rearing to go. We were full of fuel, water, and provisions. The forecast was promising. And a new adventure was about to begin.