December 5, 2024 – April 12, 2025

North of latitude 10°S – outside the “danger box” and into the “safe zone”. We now had five months of Pacific cyclone season to kill at what seemed like the world’s edge. What to do?

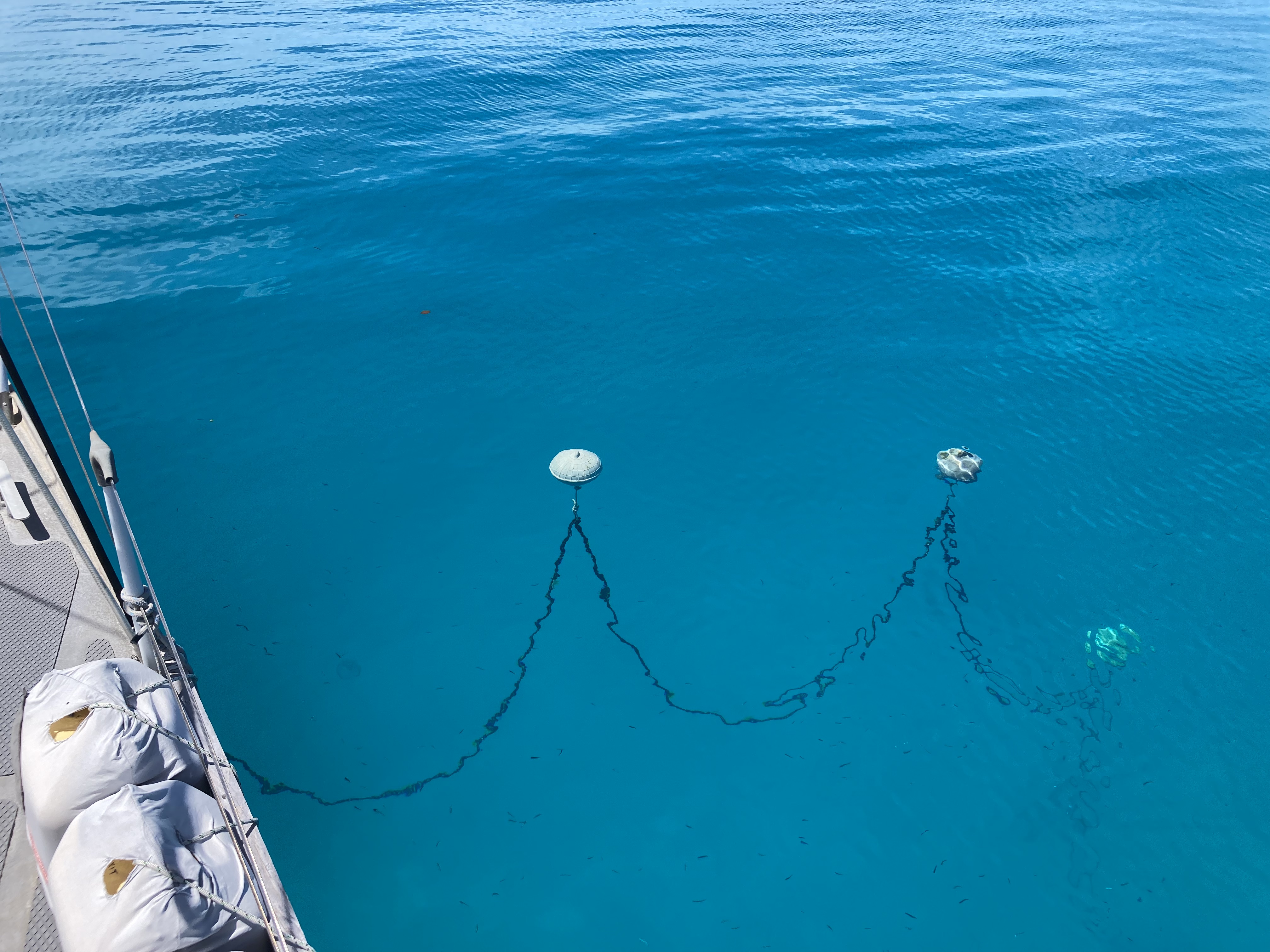

We were immediately grateful that we still had our the anchor chain floats we had acquired in the Tuamotus Archipelago of French Polynesia. Time and time again in Tonga, despite the fact that delicate coral and potential obstructions covered the anchorages, we had heard other yachties talk about how they had gotten rid of theirs the moment they had left French Polynesia. Rather than recognizing the ongoing value of floating one’s anchor chain, it seemed they had used them only after hearing that other people did so in that specific area. We couldn’t wrap our head around that particular mindset. How could it make sense there and nowhere else?

From the deck of Exit, as we now tried to anchor in Funafuti, we could see coral and potential obstructions all around. As had been the case in French Polynesia, Tonga, and Wallis, floating the anchor chain would remain our standard practice. It had seemed like an epiphany since our first moment of enlightenment.

We were more than happy to put forth the bit of extra effort required, especially when we found ourselves swinging three hundred sixty degrees over the course of a couple of days!

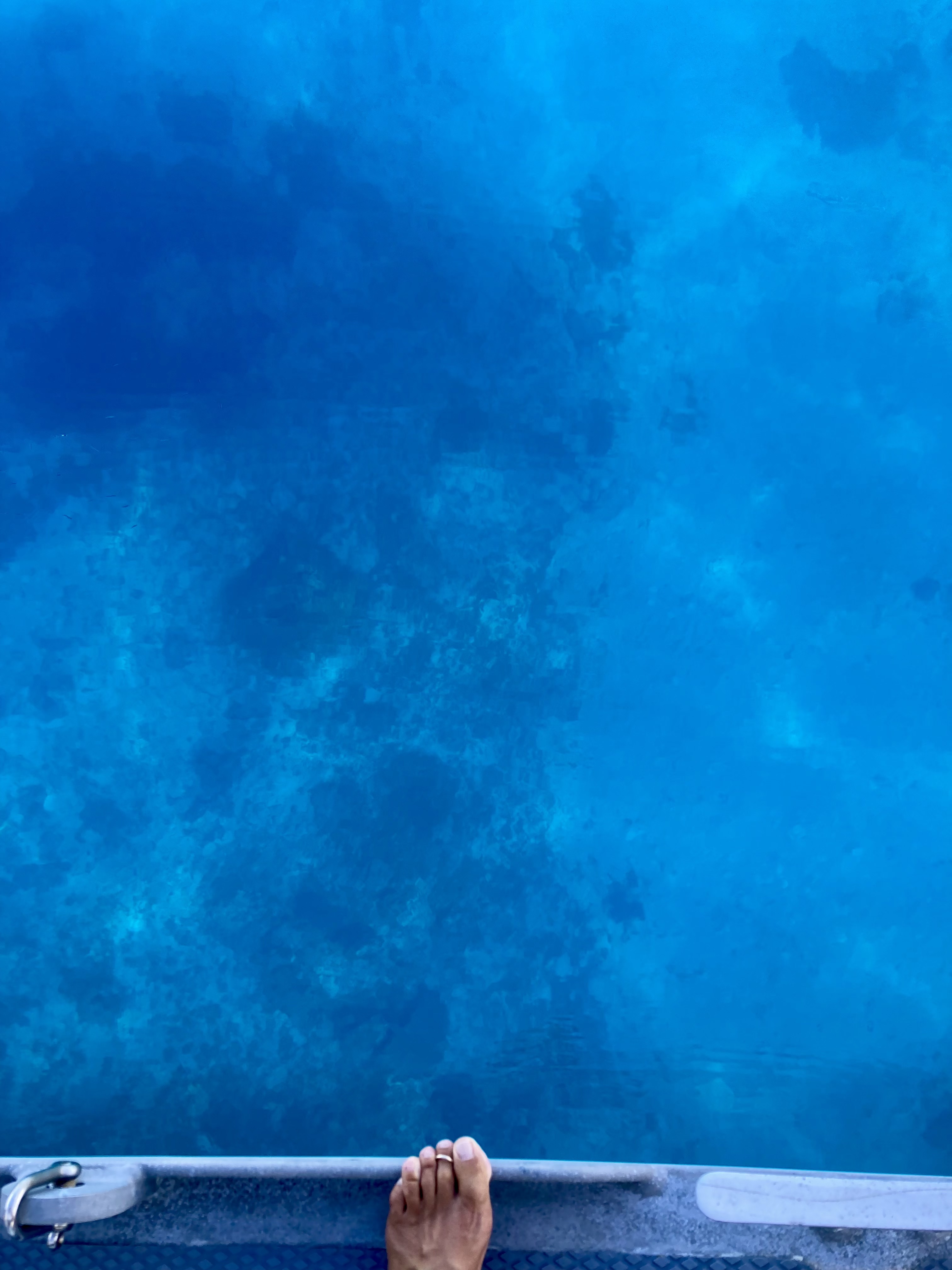

With the shadows of coral structures underwater in every direction, the building excitement of getting in the water was inevitable. And considering we had nothing but time on our hands, it immediately became apparent that diving was back on the itinerary. Even snorkeling would be a welcome way to help stave off the heat of a Tuvalu day, which we quickly learned typically ran into the 80’s before breakfast and upwards of 100°F by lunch on a sunny day.

In fact, the water temperature was so warm that wet suits were not even a consideration. Over the next few months we would experience water temperatures ranging from 85-95°F (29-35°C). At times, the water at the surface felt like you were swimming in pee. Ewwwww.

However, though the bath water temperatures provided us a wetsuit free swimming environment, we would soon learn that it may have come bearing a high price for the local marine life.

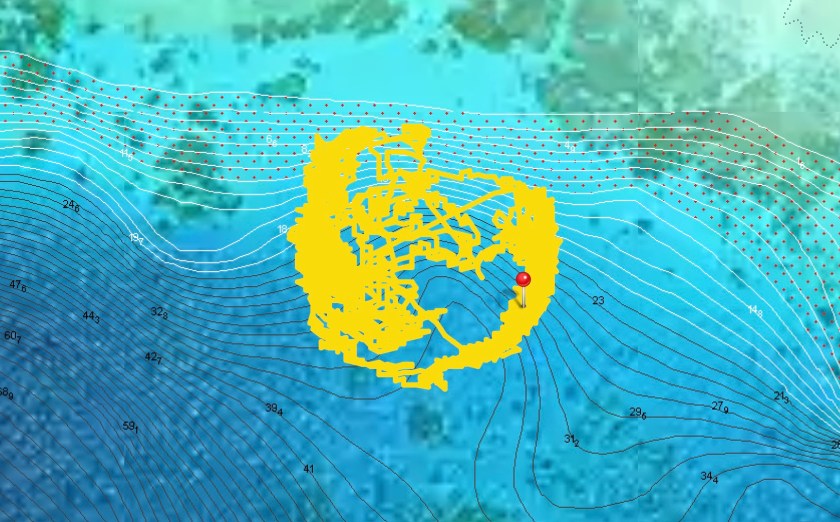

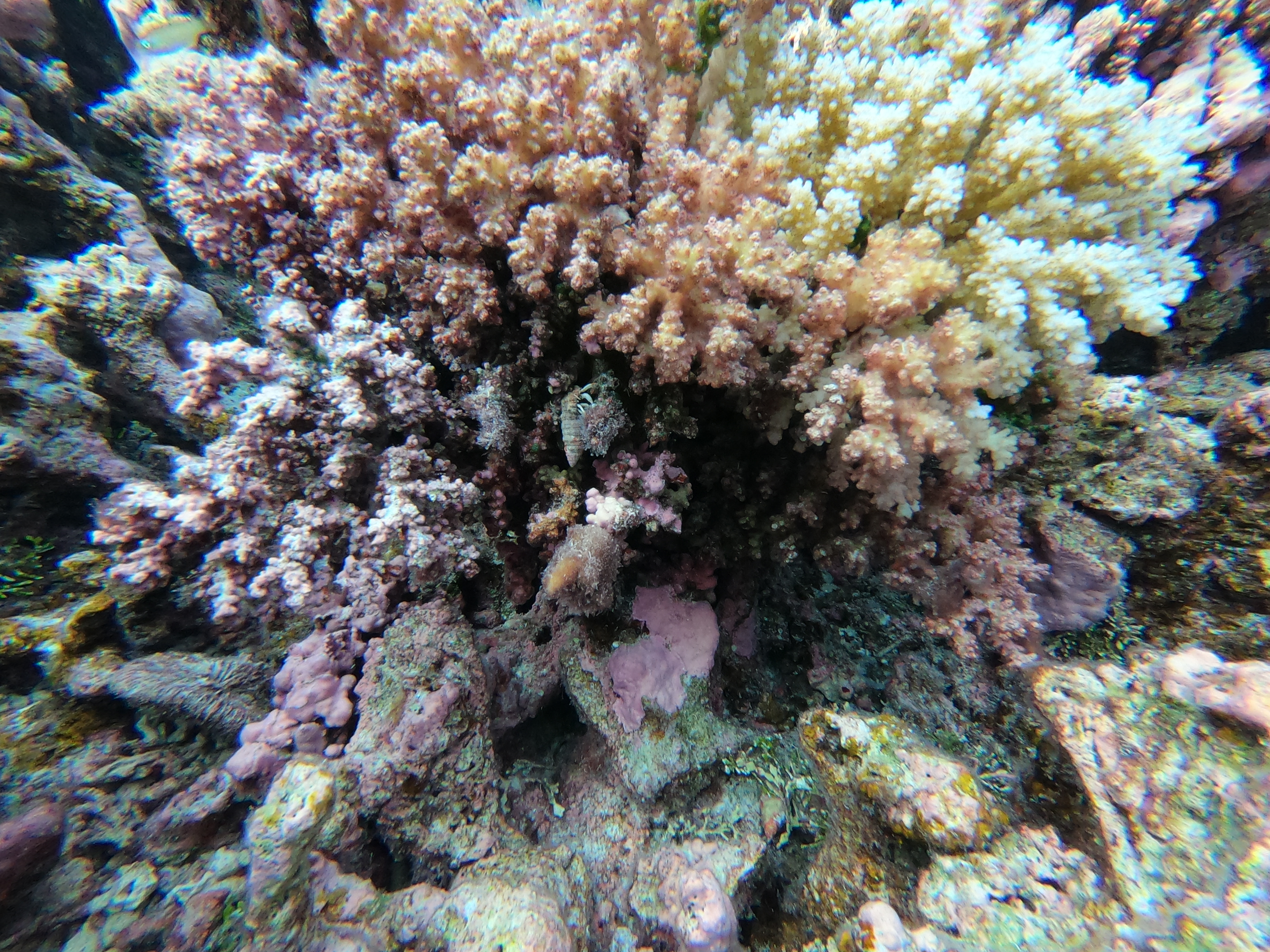

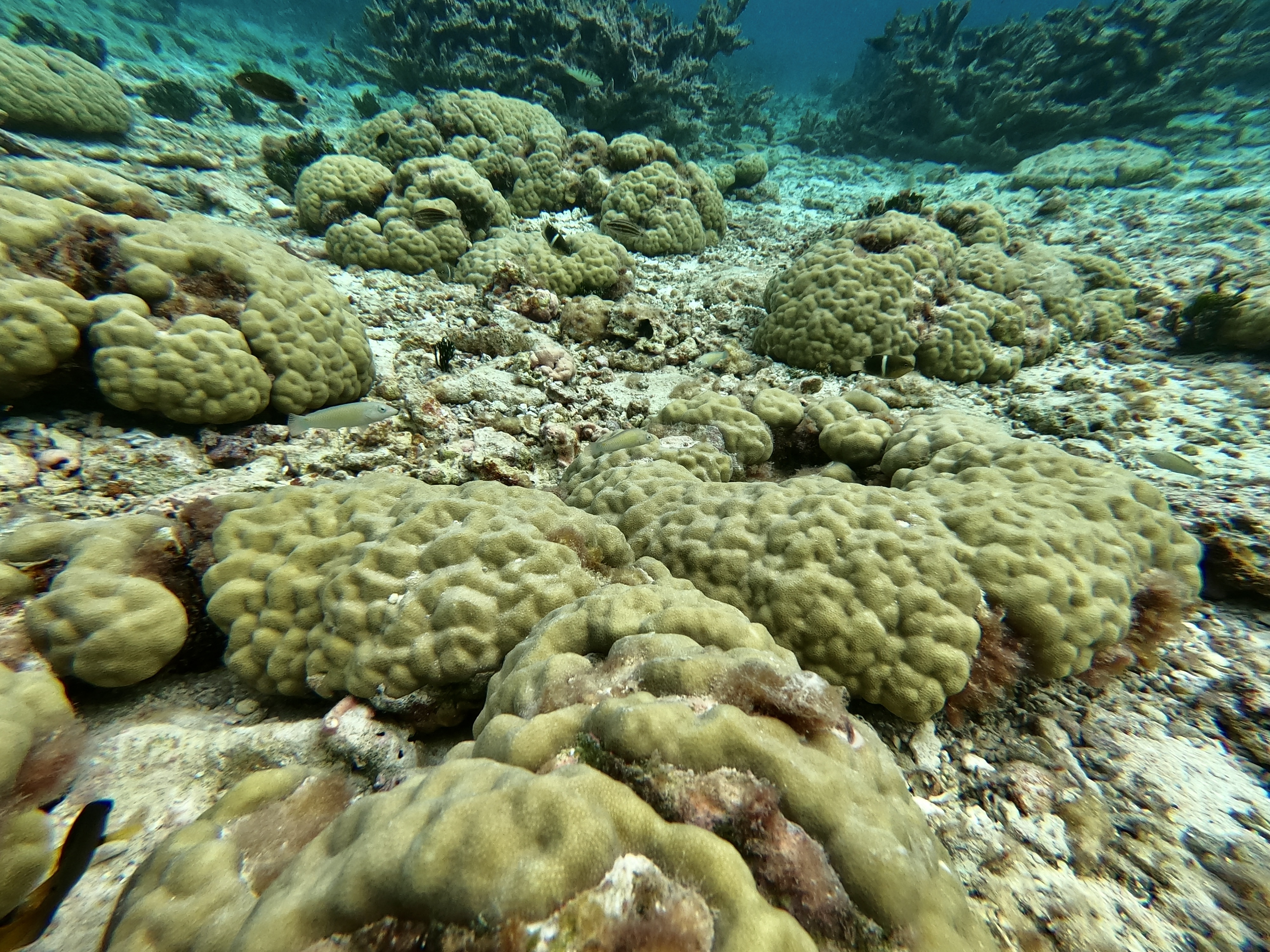

We had briefly jumped in the water while anchored right next to town, and noticed the coral bommies didn’t seem very healthy. Not uncommon, given nearby development, boat traffic, etc. However, when we dropped anchor about four nautical miles north of the main part of town, the coral also seemed nearly completely dead. We were surprised, to say the least. These were not isolated bommies; rather, large stretches near shore or large rounded mounts that rose twenty or forty feet from the bottom to within ten or twenty feet of the surface. All covered with dead coral. Almost no fish life. Puzzled, we supposed it could have been the result of storms, or some of the dredging that was happening in the town…still, it seemed really strange.

Yet, when we moved another four miles to the northernmost side of the atoll, between two tiny motus called Fualifeke & Pa‘ava, we were shocked to find exactly the same thing. We were now almost ten miles from the town, near significant amounts of water exchange from the north pass, just off two tiny islands that had less than ten people occupying a few small structures. WTF?

Location after location, and as it would turn out month after month, miles and miles of dead coral stretching as far as the eye could see. Some fish life…but not much. Almost no large reef fish. No invertebrates. Only an occasional small black tip reef shark (with the exception of a very few grey reef sharks, white tips, and a lemon shark we saw near the north pass).

In thousands of dives, we had never seen an area so extensively covered with so many coral structures and yet so devoid of life.

Almost impossible both to capture photographically, as well as incredibly difficult to try to describe, was the immensity of the coral coverage, the age and maturity and size of the coral structures and fields and, of course, the absolute scope of lifelessness everywhere. Again and again, it occurred to us that the closest thing we could think of by comparison, the only way to describe what we were seeing, was a vast underwater petrified forest of coral.

And yet, this wasn’t death and destruction resulting from an industrial accident, or building developments, or invasive tourism, or boat anchoring, or poor diver/snorkeler buoyancy, or storms, or urban/agricultural pollution, or war… or anything else we could think of. It seemed more like the depressing result of a cancer spreading within that part of the planet.

Brief videos of what we witnessed underwater in February 2025:

More dead coral and sparse marine life as far as the eye could see in April 2025:

Regardless of where we went, we found the same thing. Endless graveyards of some of the most staggering and extensive growths of coral we had ever seen. A few fish. A bit of live coral here and there. But largely a marine necropolis.

We suspected that the incredibly warm water temperatures had caused a profound impact, as well as some sort of a catastrophic bleaching event that must have recently occurred. Environmental impact from a town of only eight thousand people couldn’t have caused it. The land reclamation projects and ongoing dredging couldn’t have been the primary culprit.

A few of the areas we visited could exhibit a stunning difference in visibility within a one hundred foot distance during tidal shifts. The distinction of a cold incoming tide washing through a shallow pass and clearing up the water versus just inside where the visibility was almost zero was unbelievable.

While some locations with significant tidal water exchange, undoubtedly lower water temperatures, and better water clarity had slightly better coral condition and marine life diversity as well as numbers, they fared only slightly better, still suffering from what consistently must have been almost ninety percent mortality (compared to the ninety nine percent elsewhere).

Barely better, at best.

Despite the depressing lack of healthy coral, we were bound and determined to continue diving and blow some bubbles. There had to be something down there for us to find.

Possibly the most impressive, and unfortunately one of the few, live structures we came across during all of our dives were near one of the anchorages we discovered towards the south side of Funafuti just off the island of Mateiko. They were a pair of massive round growths of plate coral, the larger of the two must have been at least twenty feet tall. Nearly perfect spheres. Both were almost one hundred percent alive and in pristine condition…a truly stunning exception to the fields and fields of dead coral surrounding them. We had never seen plate coral grow in such a unique shape and size. It gave a rare insight into what the entire atoll must have looked like in the not so distant past. Even better was the fact that a single manta ray, the only one we ever saw there, seemed to like hanging around right in that area. Because we didn’t have an underwater housing, we could only capture a marginal and unflattering GoPro photo of the plate coral structures from near the surface, but we were flabbergasted every time we swam by.

That one manta ray provided us immense excitement, satisfaction and enthusiasm. To have a magical encounter with such a creature, not just once, but multiple times, fueled in us a hope that all was not lost for Tuvalu’s underwater community.

Occasional locations that contained a small oasis of life here or there did appear every now and then.

Thousands of what appear to be juvenile golden trevally were one of the few real schools of fish we spotted in the course of five months:

In another instance, we stumbled across an area no larger than thirty feet by thirty feet that was home to a dozen or more anemone, all inhabited by families of anemone fish. They were scattered about in an endless field of almost entirely dead coral. This was another one of those high water exchange areas; but, other than that, we couldn’t figure out how the anemone (and only the anemone) managed to survive there. It was our only encounter with anemone during our entire stay in Tuvalu.

It’s not as if Tuvalu doesn’t already have a full plate of environmental concerns to deal with currently. Still, it seemed like quite a few of the people we spoke with were unaware of the extent of the damage inside Funafuti’s lagoon. Of those who were aware, most believed it was something that had happened in the not so distant past. Posts online from only a few years back raved about the healthy and impressive coral, which would support that hypothesis.

We reached out to the Funafuti Fisheries Department hoping we might be able to contribute by donating some of the extensive free time at our disposal, offering to help gather data or survey areas we were diving at. The director, a friendly and conscientious Englishman focused on both protection and restoration of Funafuti’s marine life, graciously accepted. He asked us while diving to be on the lookout for any of the two species of Tridacna (giant clams) that were native to the area.

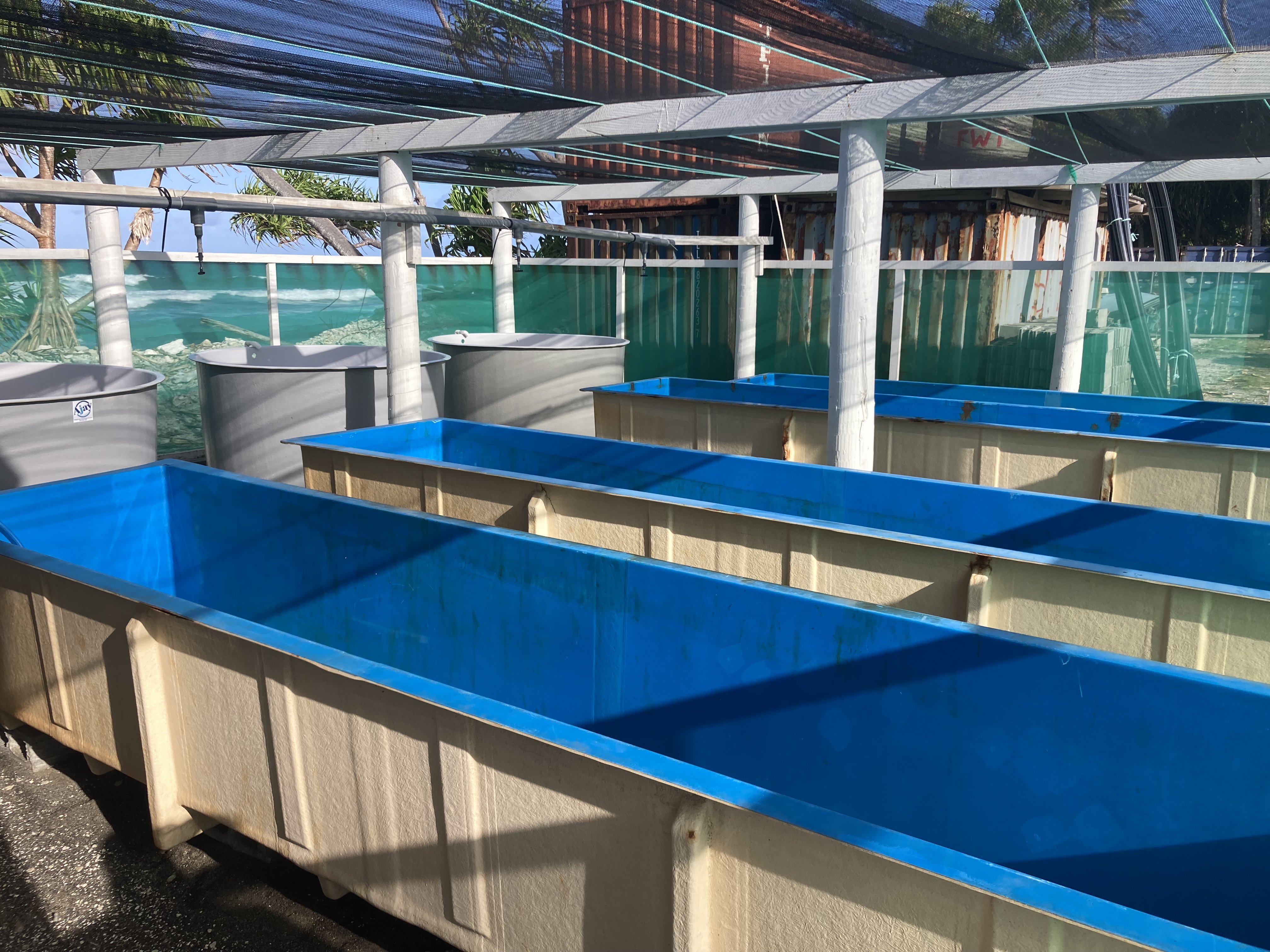

The Fisheries Department had undertaken a project aimed to rehabilitate the Tridacna population of Funafuti, which had sadly been decimated both by environmental changes as well as uncontrolled over-harvesting by locals. They had recently completed construction on a number of tanks and holding areas intending to collect some of the few remaining giant clams in the lagoon. Once in a protected environment, they could be raised and bred specifically with the objective of eventually being released back into the wild in an attempt to restore the dwindling population.

Though there are many species of giant clam, with the largest reaching as large as three to four feet across, the two species native to Funafuti, Tridacna maxima and Tridacna squamosa, are a bit smaller. The T. maxima, typically six to nine inches across, are usually found embedded among the coral and rock structures. The larger T. squamosa can grow to twice that size, and can be found sitting in the sand or rubble on the sea floor. The mantles of Tridacna, which protrude from the openings of their fluted shells looking like giant fleshy lips, can be found in an unbelievable variety of stunning and contrasting colors, often making them stand out distinctly from their surroundings.

We diligently kept an eye out for both Tridacna maxima (the smaller of the two species) as well as Tridacna squamosa every time we were in the water.

Sadly, during five months of snorkeling and diving, we managed to see only one very young giant clam (T. Maxima), embedded in a endless stretch of dead hard coral. Unfortunately, we had seen it within the first month of our arrival, well before we had made contact with the fisheries department. We never found it a second time.

Even more sad, was the evidence we repeatedly came across…testimony to the over harvesting of giant clams that had undoubtedly contributed to the current situation. In one location alone, not more than twenty feet square, we found the empty shells of more than a dozen of the larger Tridacna squamosa. All mature. All over a foot across in size. All dead.

A graveyard for a nearly extinct species of Tuvalu native. It appeared to us that, barring the introduction of giant clams brought in from outside the area, it was already too late for the Tridacna.

Ironically, this seemed to vividly represent a dystopian vision of the entire country’s future. It was both a depressing and sobering realization.

As the most advanced species and supposed stewards of the planet we live on, it is entirely up to humans to stop the ongoing destruction of Earth, especially the devastation we are causing directly. If we continue on our current path, failing to take drastic and decisive immediate action, Tuvalu represents but a microcosm of what is to come for us all. The oceans are our planet’s heart and lungs; it may already be too late to prevent the global extinction that is well underway. Though lies are told every day by people on both sides of the aisle and unscrupulous assholes will always cash in on opportunities to profit, global warming is real. Climate change is no hoax. Science is not bullshit, no matter how little you want to hear it.

Author’s note: Months after departing Tuvalu, while in Fiji, we spoke to a local dive guide, Leone, who had recently been helping aboard “Argo”, a globally traveling National Geographic research vessel equipped with extensive scuba facilities as well as a three person submarine. He was acting as a guide/consultant while the team gathered marine conservation data in Fiji. “Argo” had been in Tuvalu at the same time we had been there. Leone relayed to us how stunned the crew aboard “Argo” had been upon witnessing the underwater devastation around Tuvalu, even outside the lagoon. At appeared they concurred with the conclusion we had reached – Tuvalu’s current situation was almost certainly due to increasing water temperatures which had either caused a catastrophic bleaching event or longer term mortality of nearly all the coral life.