April 12 – May 5, 2025

How do you become #1?

Well if you’re SV Exit, it’s certainly not by entering a race. Speed is definitely not one of our distinguishing qualities; nor something we particularly give a shit about. In fact, the whole concept of mashing in amongst a massive horde of sailboats struggling desperately to get past everyone else to reach the front of the pack has never held much appeal to us. Much appeal…who am I kidding? The idea ranks right up there with volunteering to be a proctology exam training model.

The path less traveled…the one where you don’t see anyone either in front of or behind you. Now that’s more up our alley.

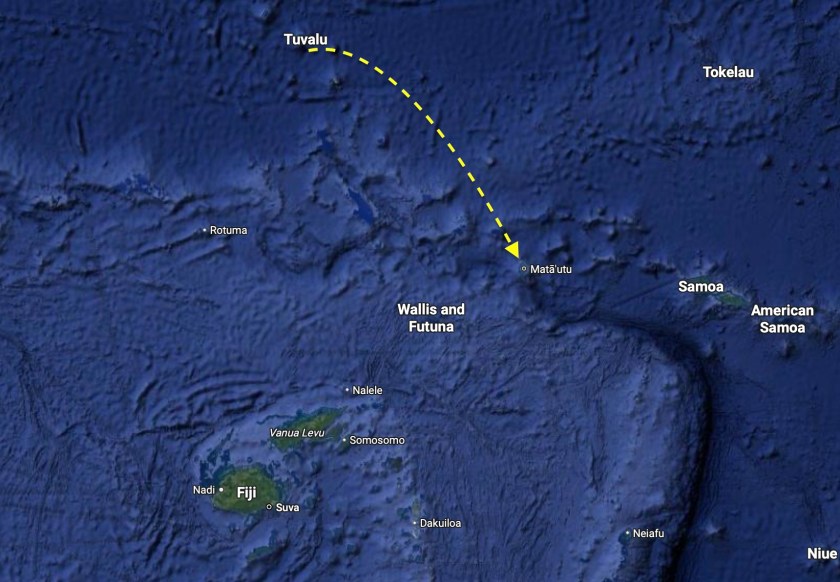

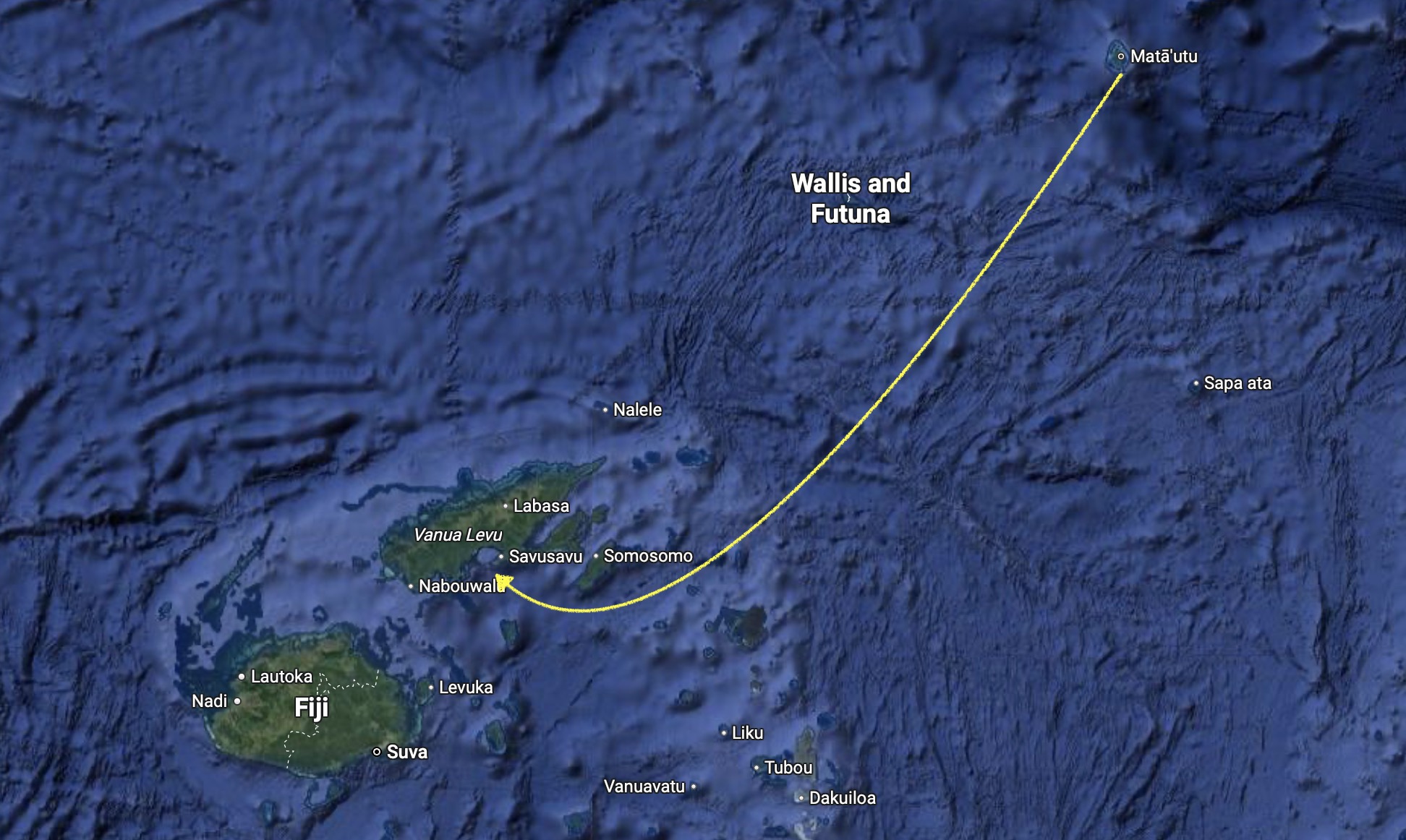

As it turns out, if you depart the Kingdom of Tonga heading in exactly the opposite direction of mostly every other sailboat in the South Pacific…spend four and half months as pretty much the only sailboat in the tiny country of Tuvalu…and then sail back south nearly five hundred nautical miles before the cyclone season officially ends…there’s an excellent chance that you will be the first boat of the year to clear into Wallis and Futuna. And that’s exactly what happened. Exit…#1.

But that’s jumping a bit ahead in the story.

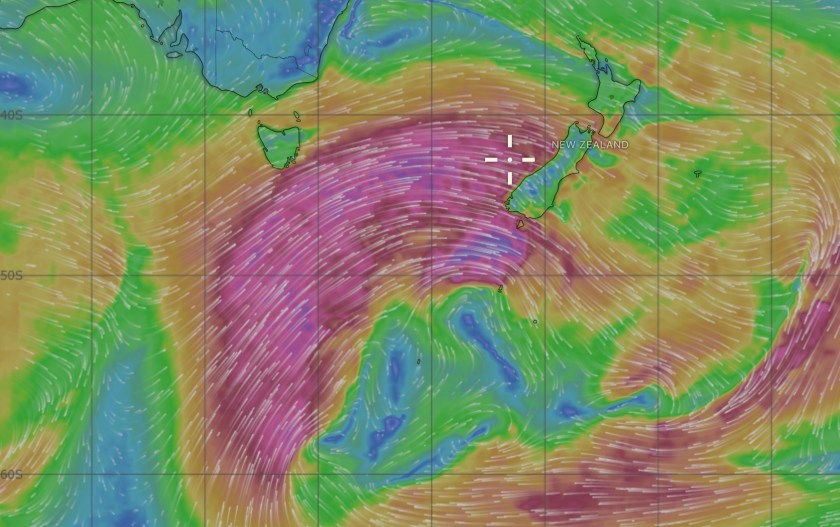

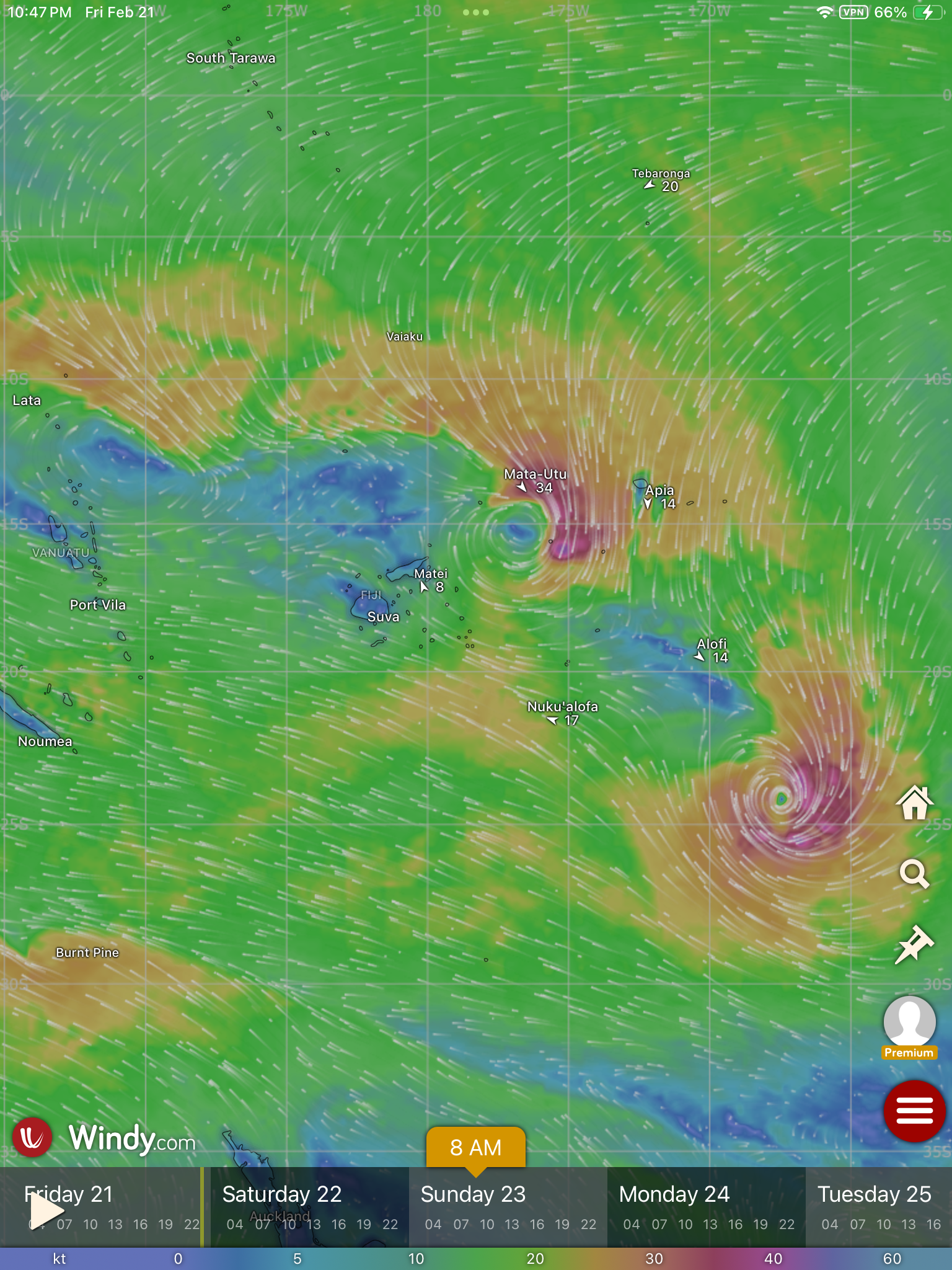

In some circumstances, threatening gray skies facing us and a distinct lack of wind, as was the case departing from Tuvalu, could be due cause for concern. But we were ready to go, regardless of the situation. If we were fortunate enough that the weather forecasts we had carefully studied were correct, the rains would be minimal and short lived, and we would find good wind for sailing a bit to the east.

Exit’s trajectory would carry us between four and five hundred nautical miles back to Wallis and Futuna, the country we had briefly passed through on our way to Tuvalu in November.

A forecasted north wind that was supposed to materialize a bit east of Tuvalu sent us initially heading in what appeared to be an odd direction. The plan of action – motor east for a short period instead taking a more direct route that would force us to motor for even longer in the long run. After nine hours, that strategy paid off as a north wind actually came to fruition. We finally were able to shut off the diesel engine and sail through the night under the brilliant visibility of a full moon.

Just as we were crossing the International Date Line at 180° Longitude, a big squall passed over us, unleashing a torrent of rain and forcing us to sail under a double reefed main with only a scrap of our solent sail unfurled.

After a wet night, we were treated to a calm day of respectable boat speed and very little motoring.

The choice to leave Tuvalu two weeks before the official end of cyclone season had not been a haphazard, reckless, or senseless decision. It had, however, been quite impulsive and spontaneous. We never regretted our choice to spend the cyclone season in Tuvalu. For the most part, everyone we encountered had been very good to us and our experiences had been positive. We very much appreciated being allowed to extend our stay. And yet, it was time to go.

After four and a half months, we had simply reached our limit.

It was questionable if our propane would last much longer. Our provisions were still holding up but we were having to get much more selective and our choices were diminishing. Our dive compressor was suddenly out of commission. Our wind sensor was dead. Our fresh water pumps were on their last legs. We were tired of drinking shitty boxed wine (back in Panama during the COVID lockdown, we had gotten used to drinking a marginal boxed wine called “Clos“. We would joke that it wasn’t even good wine but it was “Clos”. Now the joke was not only was this boxed wine not good…it wasn’t even “Clos”).

Even more maddening was Funafuti’s Town Council, whose permission we now needed in order to move due of the misbehavior of one boat prior to our arrival, which had now completely ghosted us. This was undoubtably the most frustrating part of our current situation. In the end, those jerks on that catamoron, as well as the Town Council, turned out to be the only ones that we really felt deserved to be archived in the asshole column.

The list of grievances really wasn’t that long. But, if we stuck around, we’d just start to wallow in self-pity.

Our utter and complete failure to have our dive compressor parts, masthead wind indicator sensor, and replacement freshwater pumps successfully shipped to us in Tuvalu had proven to be the proverbial final nail in the coffin. Though we had already paid over US$350 in shipping costs, the levels of frustration we experienced after learning DHL couldn’t get the package any closer than Fiji for the next month was calamitous. Nothing could be more annoying, vexing, irritating, exasperating, infuriating…all of the above.

Oh…wait. It turns out I’m completely wrong on that.

Before clearing out of Tuvalu, we had been assured by DHL that our package – the one that had already been sitting on a pallet in Fiji for three weeks – would remain in Fiji so we could pick it up there once we had arrived. Then, a mere twenty four hours after we had cleared out and departed Tuvalu, we received a subsequent email from DHL. It stated, “We are happy to inform you that your package has just been delivered to Tuvalu!” Oh, those fuckers. I thought Kris was going to have a stroke right there in the cockpit.

Fortunately, instead of throwing her iPhone overboard, she contacted DHL once again, for what must have been the thirty eighth time, and avoided directly calling them the dumbasses that they were; instead, managing to maintain enough composure to arrange the logistics of having the damn box returned BACK to Fiji. Holy shit!

It was water under the bridge. Now we were underway. Tuvalu was behind us and the situation with DHL was out of our hands. The only thing that mattered was keeping Exit sailing in the right direction…and enjoying the freedom of being sailors on the open sea.

Kris drew the short straw on the second evening when relentless rains coincided with her overnight watch in the cockpit. However, the beautiful conditions which accompanied the following day more than made up for the previous night.

Even better, midway through the following afternoon, Kris suddenly jumped up and enthusiastically called out, “FRIENDS!” A pod of dolphins had found us and, until they decided we were simply not moving fast enough, seemed content to dart back and forth playing just in front of our bow wake.

A person would be quite hard pressed to find a better way to occupy one’s day.

An extraordinary day nestled between bright blue skies and an intense shade of indigo seas in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean, with nothing more than the wind filling our mainsail and dual headsails to move us along at five to seven knots of speed, complete with a lengthy visit from dolphins…how do you top that?

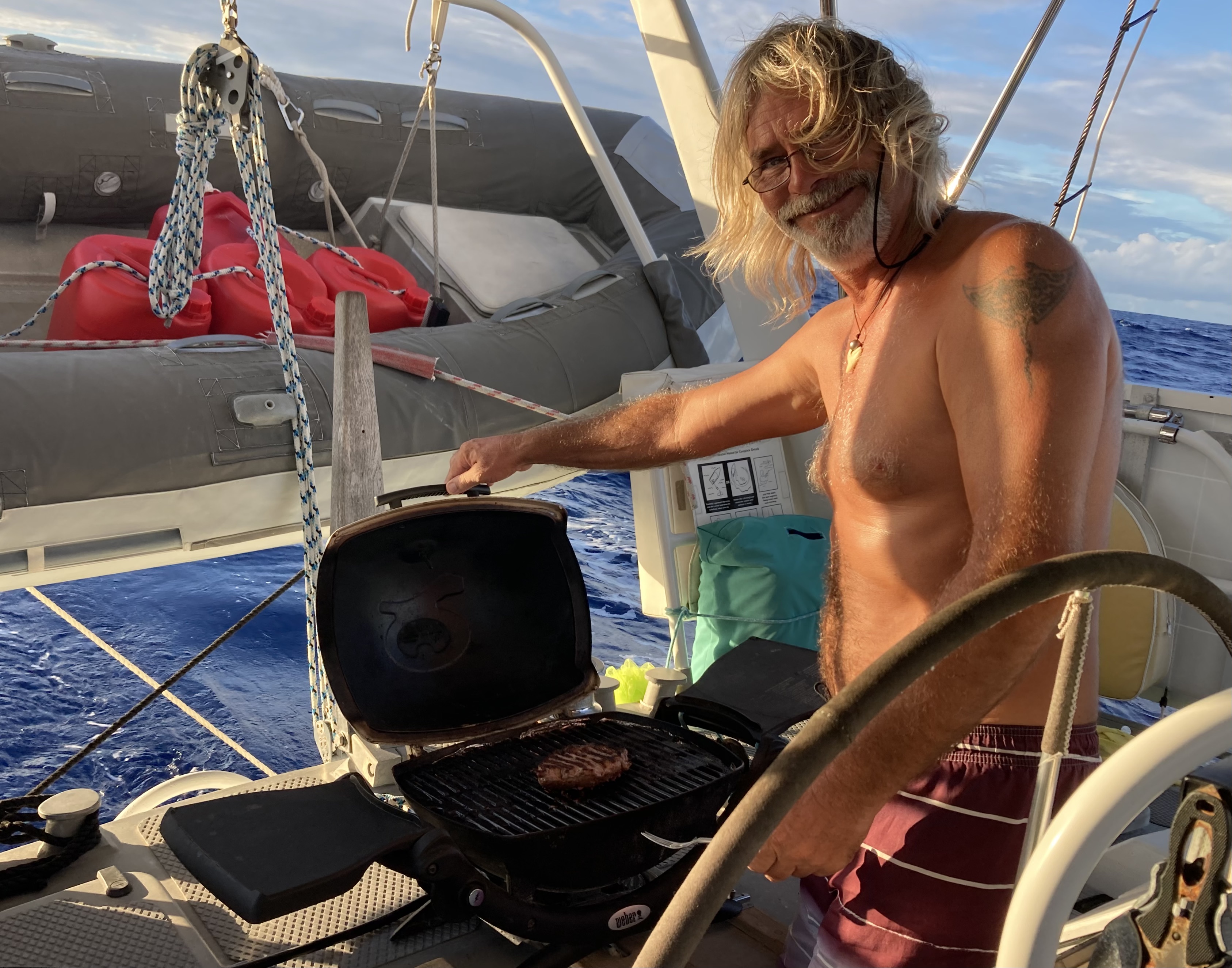

Why, of course…with a barbecue on deck in fifteen thousand feet of water!

The fading light ushering in an Oceania sunset only seemed to put an exclamation mark at the end of a near perfect day.

The following morning was equally stunning as the dawn of a new day arrived. It had been our first dry night of the passage. Still, we were treated to an early morning rainbow, compliments of a squall we had apparently miraculously avoided.

By afternoon of our third day underway, it had been twenty four hours since we had seen any rain. Though at times we could still see the ominous cloud banks of squalls stacked up on the horizon in various directions, it appeared we were now successfully threading the needle between them.

Our progress, slow but steady, was actually much faster than we had expected. We had expected the passage to take at least four days, possibly as many as six.

Now after seventy two hours, having just completed three days at sea, we only had ninety nine nautical miles remaining to reach Wallis. Even creeping along, we would make it before sunset the following day…the best case scenario we could have hoped for.

Unfortunately, just before midnight the wind died completely and the engine had to be fired up.

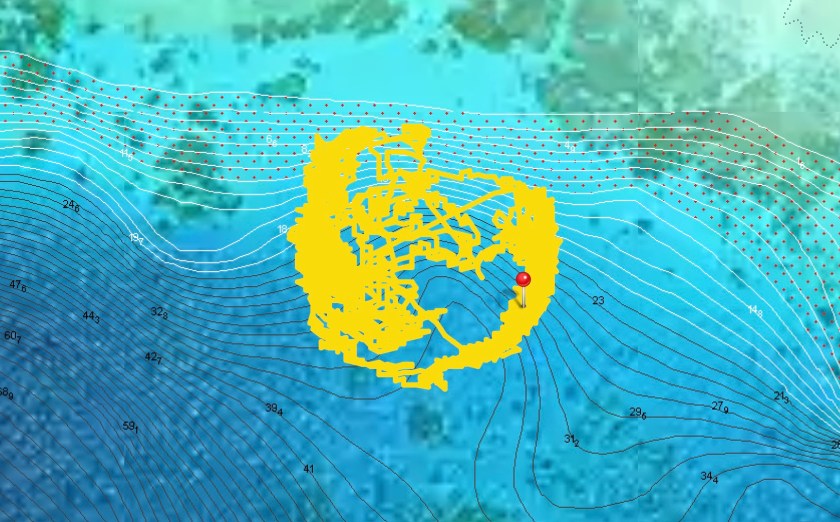

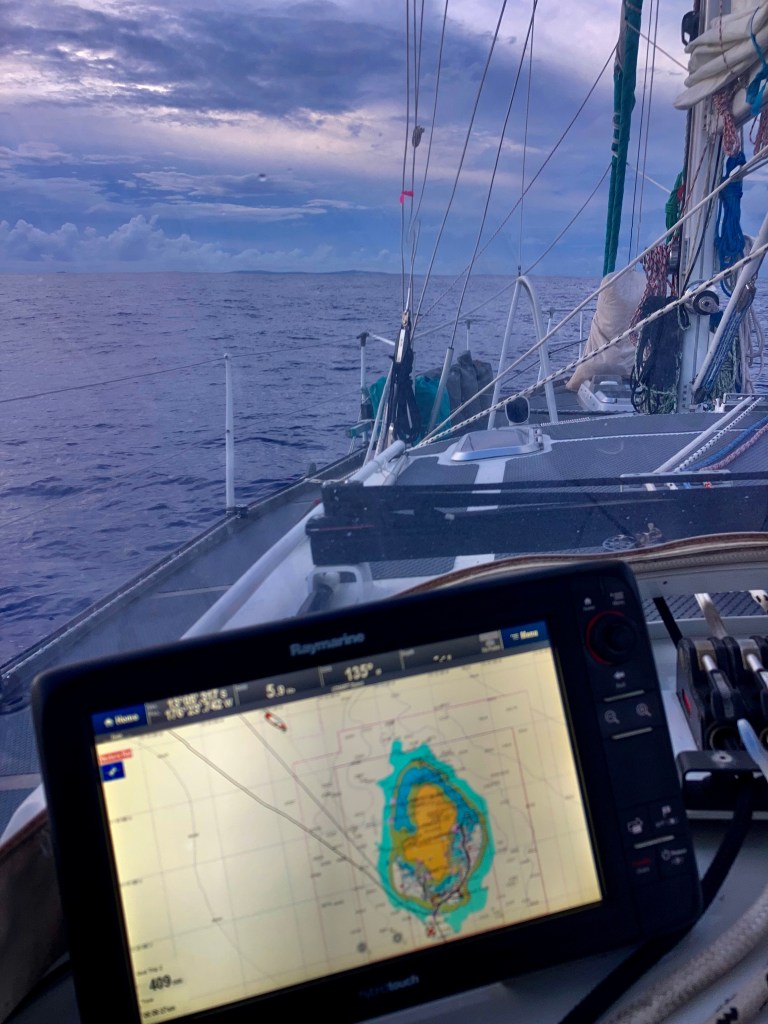

As the sands of the previous day’s hourglass ran out, I watched as the screen of our depth meter suddenly began registering numbers again instead of the dashed lines we had been seeing for days (our depth sensor display reads “—” once we are over depths of anywhere from four to seven hundred feet, depending on the water clarity and possible influence of thermoclines).

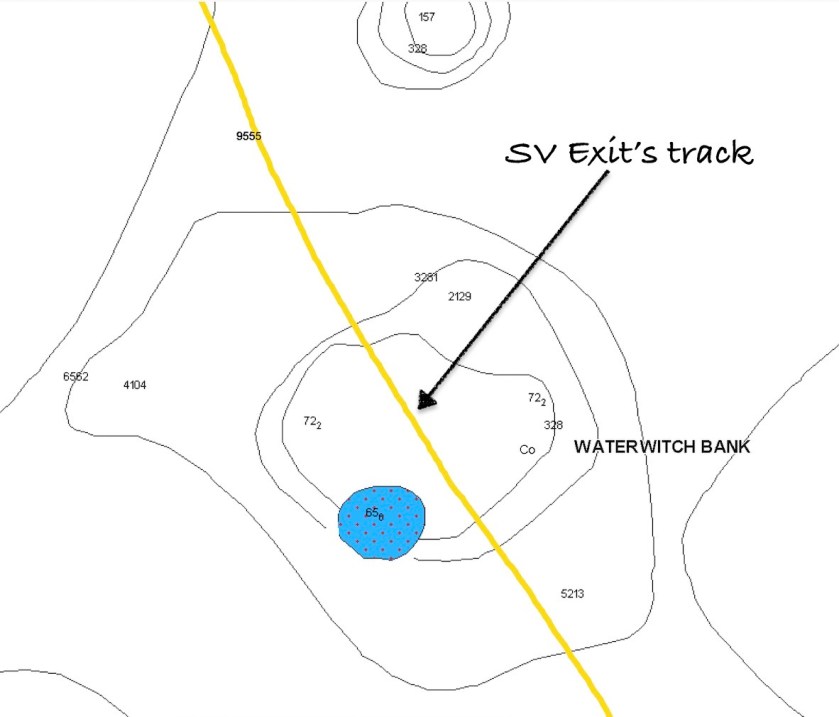

This change in depth was due to the fact that we were just passing over the Waterwitch Bank. For two hours I watched the display on our depth sensor fluctuate between one hundred sixty and as little as ninety feet. A bit disconcerting, knowing the depths under Exit’s hull had been between ten and fifteen thousand feet only a short time ago.

Less than a mile away, our chart indicated that the Waterwitch Bank, literally a three thousand foot tall stone needle of a pinnacle atop a ten thousand foot underwater peak, reached up to within sixty five feet of the surface! A depth suitable even for beginning scuba divers to reach.

Had the sun been up, with no wind and Exit sitting calmly adrift, we could have had one of those ultra rare chances to done our scuba gear and see what exactly was hidden just below the surface hundreds of miles from land. After all…incredible mysteries abound in the vast ocean just waiting to be discovered.

A hidden coral oasis? A secret cleaning station for mantas or thresher sharks or oceanic white tips? A mound of empty sand?

Alas…another one of Neptune’s secrets would remain intact. In the middle of the ocean, in the middle of the night, even with a nearly full moon above us, we would not be attempting a dive. Instead, with a slight sense of melancholy, we motored on. Wallis was now only about fifty miles in front of us.

The nearly full moon far outshone any potential glow from lights that normally would have revealed Wallis in the night’s darkness. However, as the eastern horizon began to redden with the coming of the rising sun, through binoculars we could barely start to make out the outline of Wallis’ lights on the horizon as we approached within twenty miles.

By 6am, the dark shadow of Wallis was looming just over the horizon line, right in front of us. Land ho!

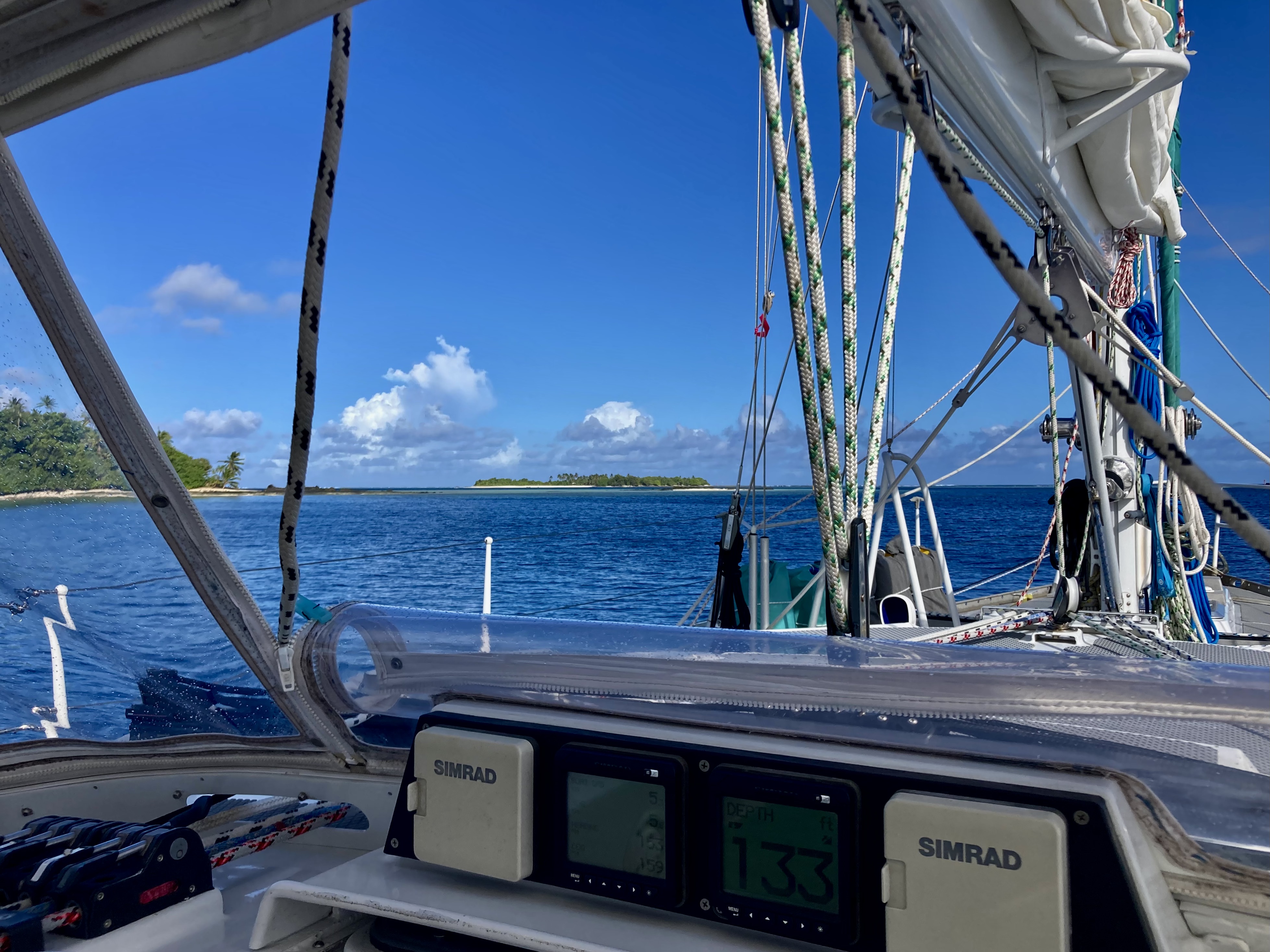

The only channel into the atoll large enough for Exit to safely pass through lies on the south side, which meant we had to sail the length of Wallis from north to south just outside the reef before navigating through the channel. Once inside the atoll we had to wind our way back north past reefs and bommies for nearly ten miles, along the main island of Uvéa, until reaching the main town of Matā’utu, where we could anchor in front of the nearby island of Íle Fungalei to clear in. A bit of a roundabout, but what can you do?

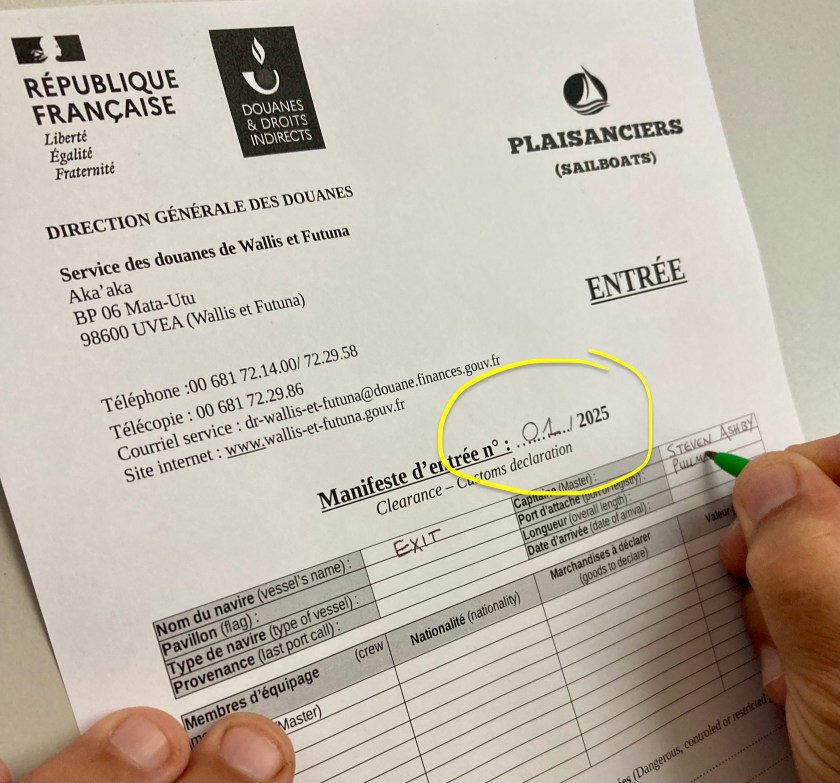

We had returned. And this time, we were the first sailboat of 2025 to arrive in Wallis and Futuna…Boat #1!

Even though our grasp of the French language was still limited to merely a handful of words, this time around we knew the procedures, which made clearing in a breeze.

While at the Gendarmerie (French police station), we also learned that the Wallis and Futuna military, as well as local police, were coordinating week long exercises that would commence in a couple of days. The country’s two naval warships, as well as military planes, and some visiting vessels would be present and busy over the following week. Various scenarios, including natural disasters and other undisclosed simulations, would be run for training purposes.

Our previous visit had been too brief to sort out a car rental in order to explore the island, but this time we were motivated to make it happen. We got a recommendation from the immigration officer of where to go and went there straight away after clearing in. Our timing was impeccable. We were informed that come Friday, every rental vehicle had already been reserved for the upcoming military training exercises and would be unavailable for a week. Today was Wednesday. Which left tomorrow wide open for rentals…perfect.

The car rental adventure took us past stunning architectural examples of Wallis and Futuna’s obvious dedication to their churches as well as beautiful scenery which stretched alongside the handful of paved roads connecting Uvéa’s individual communities together. Over the course of the day, we found many more back roads…

…and eventually even outback trails.

Without managing to completely lose our way, become the victims of a flat tire, or experience a mechanical failure, we eventually stumbled across something we had truly been missing out on for the better part of the last five months…pampered civilization.

Between the rental car and spoiling ourselves at the restaurant/bar, the day had been an unequivocal success. Worth every penny…or more accurately, every franc.

Many more francs were then spent over the course of the next few days as we restocked our lockers with the decadent supplies we had depleted since our last visit to Wallis.

Finally, after trips to the fuel station, hardware store, and multiple grocery stores, our fuel jerry cans were topped up and Exit’s lockers were back to brimming.

As the day wound down, we found time to enjoy one of Wallis’ stunning and serene sunsets.

The culmination of our days of hard work included a return into town to reward ourselves for another successfully completed mission of reprovisioning…with a pizza to go. On the way back to the causeway we happened across an outside evening celebration and Easter service at the church which delayed us long enough to result in a dinghy trip back to Exit in total darkness.

The following day, the bay became abuzz with activities as the military training exercises commenced which included fly-bys, paratroopers leaping out of planes, and apparently even plane crash simulations ashore.

We found ourselves even being buzzed directly overhead multiple times by one of the military’s planes.

At the moment, we were anchored just off of the pair of islands called Fungalei and Luaniva, about a mile away from the main town of Matā’utu. Despite having been assured by the very helpful and friendly officers at the Gendarmerie that we would be okay anchoring at our current location, we weren’t exactly sure how busy things would get once the two navy warships currently tied off on the commercial dock started moving about.

The following day, both navy ships motored away to the south. They ended up spending most of the time at the south end of the atoll, where we had considered moving to in order to avoid all the action. It turned out we had chosen well to stay put.

While talking to the officers at the Gendarmerie during the process of clearing in, we had half joked that we would be happy to hail the military via our VHF radio with a simulated mayday distress call if they wanted to add that “surprise exercise” into the itinerary. At the time, they had laughed at the idea, but not taken us up on the offer.

Which is why we were quite flabbergasted when a “Sécurité, sécurité, sécurité” hail came out over the VHF the evening that the navy ships had headed south.

“Sécurité” is the lowest priority of three main international maritime safety calls, generally considered a communication used to announce potential dangers to other vessels regarding navigational hazards or weather warnings. The other two,”Mayday” and “Pan-Pan”, are requests for assistance, largely differentiated by their degree of urgency. “Mayday” is a distress call for immediate help indicating an imminent danger or a life-threatening emergency situation versus “Pan-Pan”, which is a less urgent distress call indicating that help is requested but the situation is not immediately life threatening nor is the vessel sinking.

The “Sécurité” had been issued by a group of Australians aboard a sport fishing power trawler that had arrived at Wallis a couple of days before. We listened as one of the navy ships answered, asking if the vessel required assistance. Apparently this was no simulation. The Australians indicated they had actually run aground on the reef just inside the atoll’s entrance pass. Eventually, they were able to get off the reef later that night without assistance once the tide had risen. No life threatening emergency but definitely some evening drama. Sometimes the VHF radio provides more entertainment than any television could.

We later learned they had run aground simply because the helmsman had been focused entirely on watching the chart plotter instead of looking out the window at what the boat was actually doing. Currents inside the pass had spun them around a bit in the narrow channel, and before anyone realized what was happening, the helmsman had motored straight onto the reef…the price they paid was a bent prop shaft. Duh.

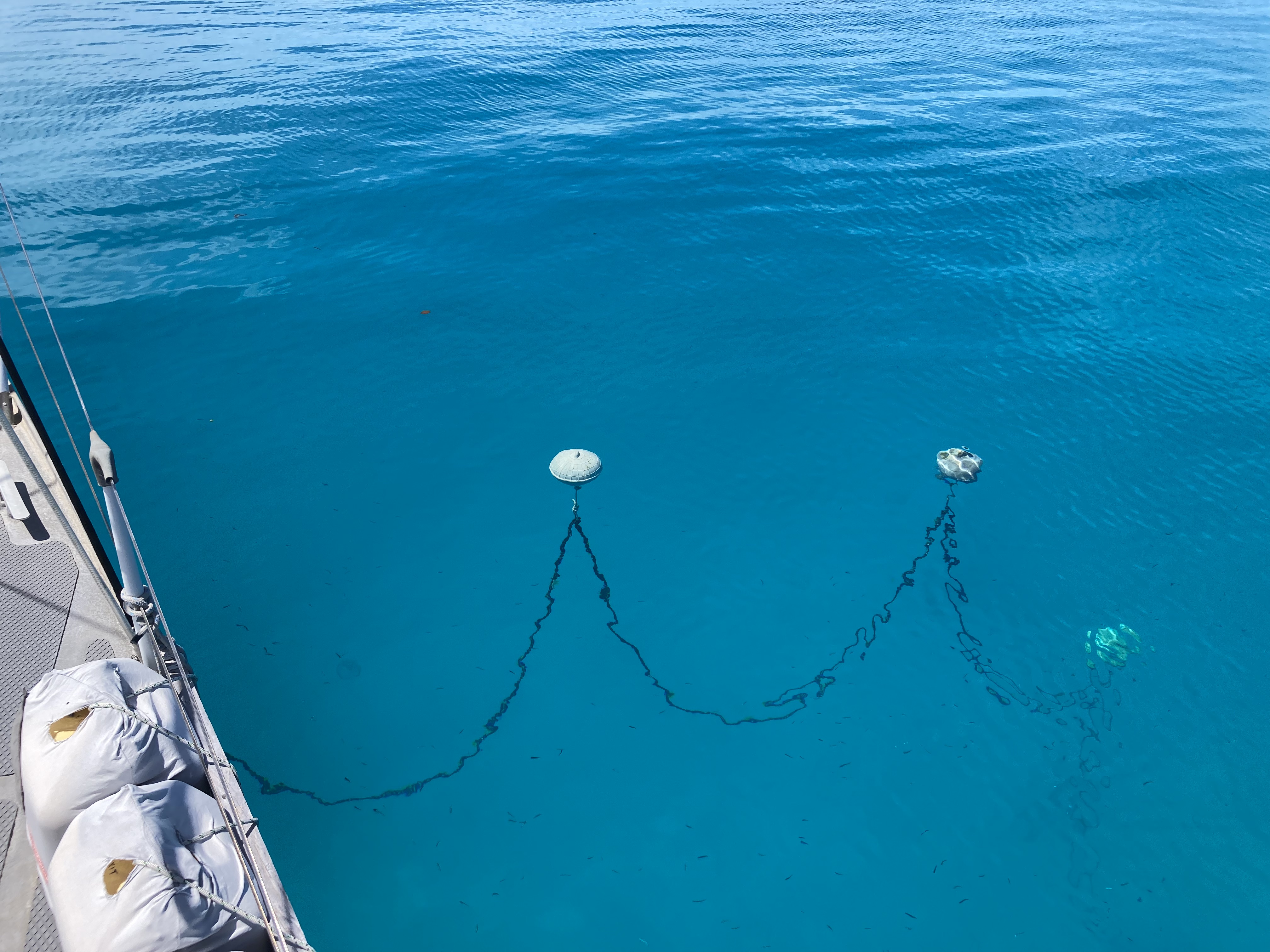

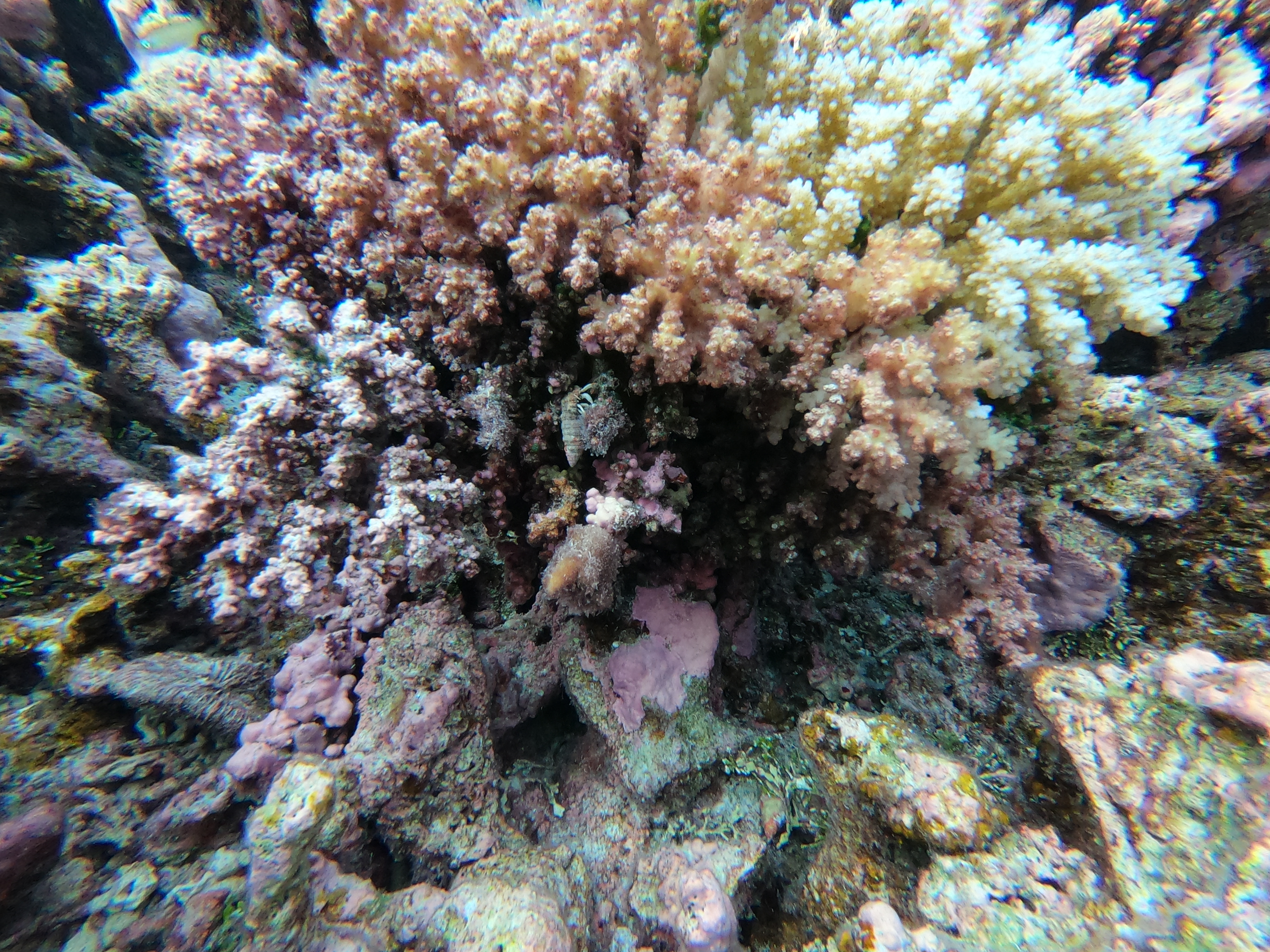

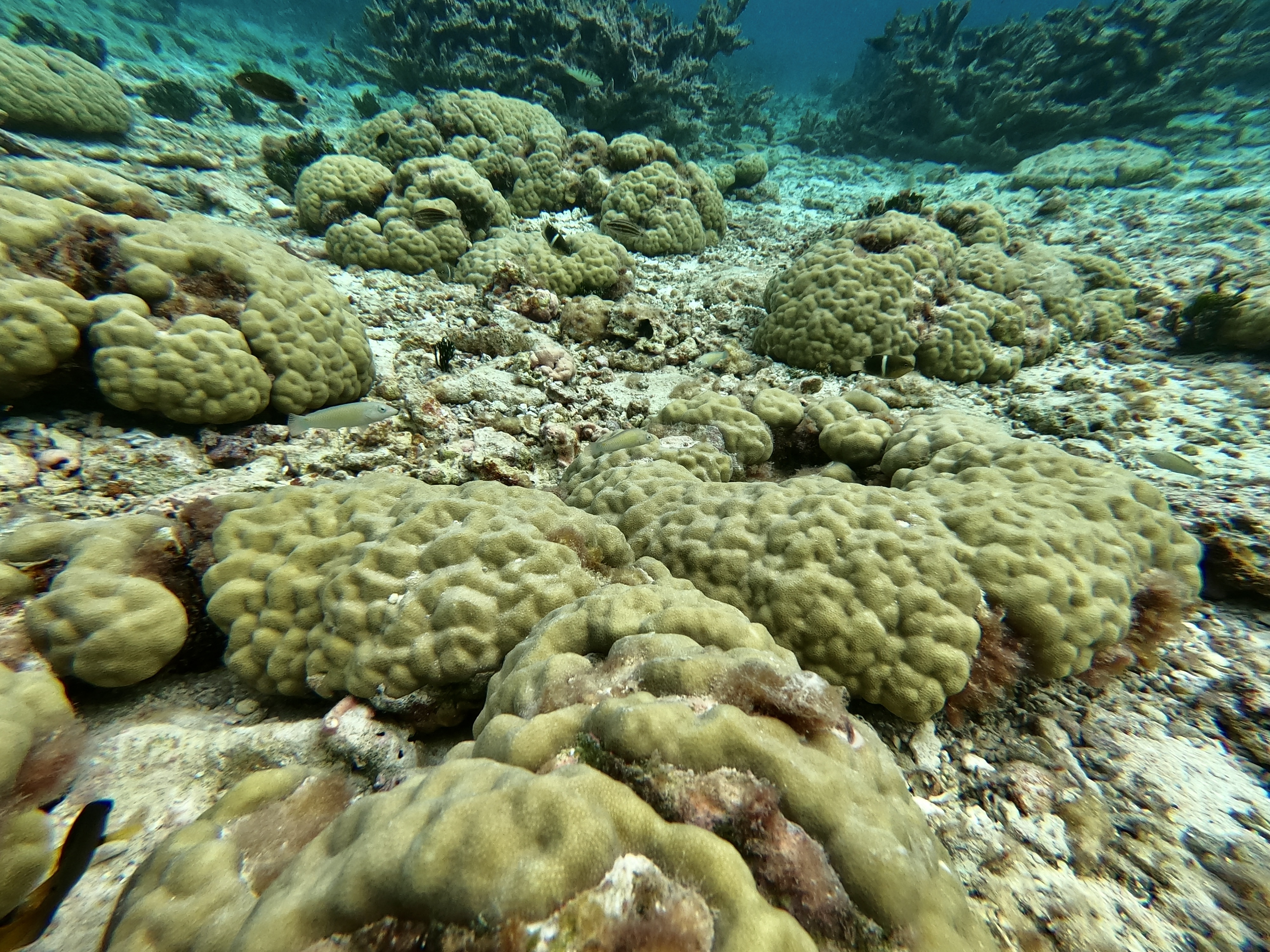

The following day we took the dinghy to an area we had never explored, located behind Íle Fungalei and Íle Luaniva where we were currently anchored. The small blue hole we found provided the best snorkeling we had experienced in half a year. Actual live coral again. Woohoo!

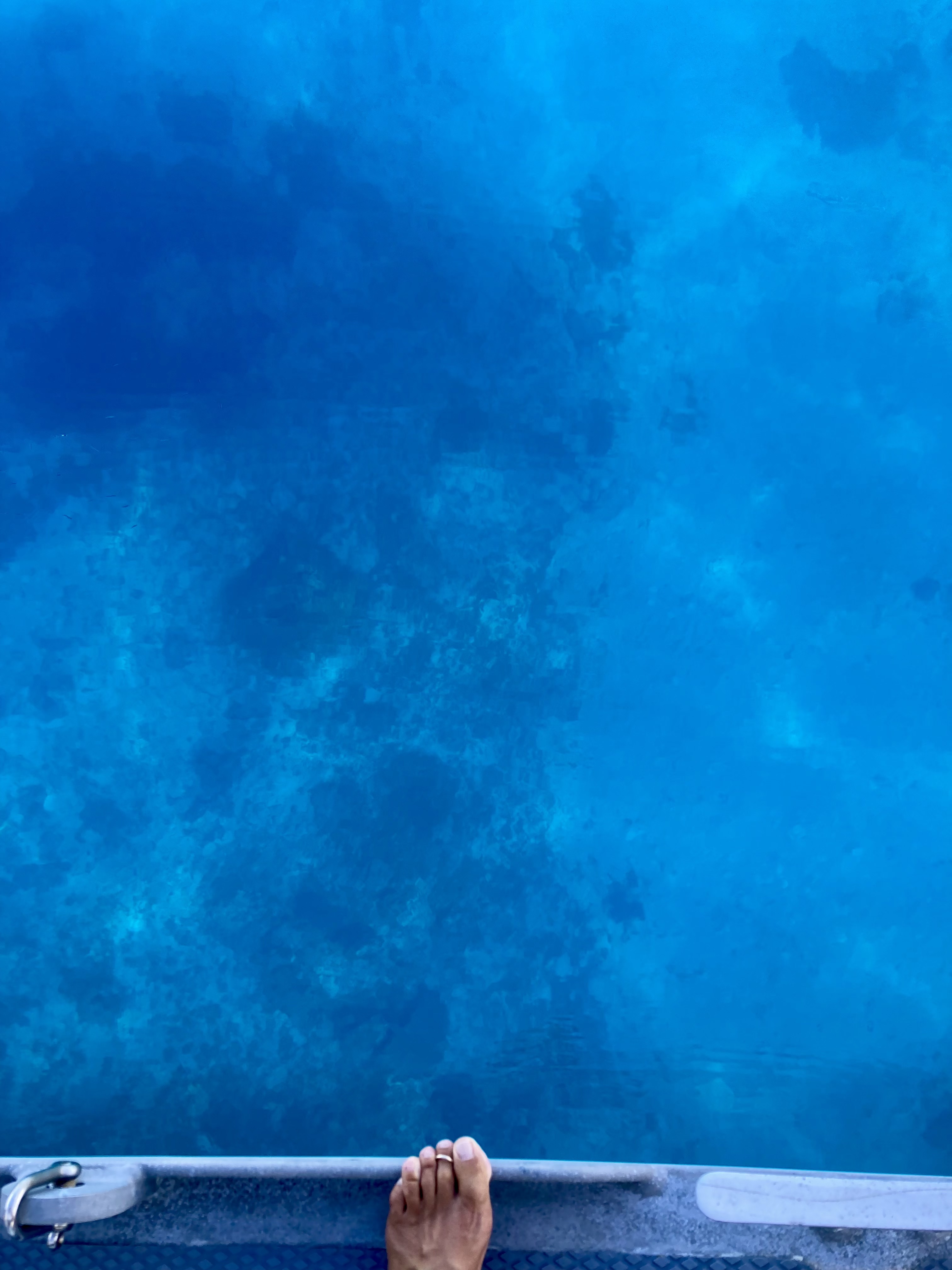

Considering all the military activity in the main bay, as well as the great snorkeling and fabulous above water views in the new location we had just stumbled across, we were instantly sold on moving Exit. We anchored near a tiny island called Nukuhifala…

…where we found ourselves enjoying a postcard perfect view at anchor.

During a trip ashore to Nukuhifala, we discovered that the island was completely uninhabited. The only structure was an open air church of some sort. Immaculately clean, it was obviously visited regularly, but was simply a large area for occasional gatherings without any additional rooms or facilities.

It would be a week before we picked up anchor again.

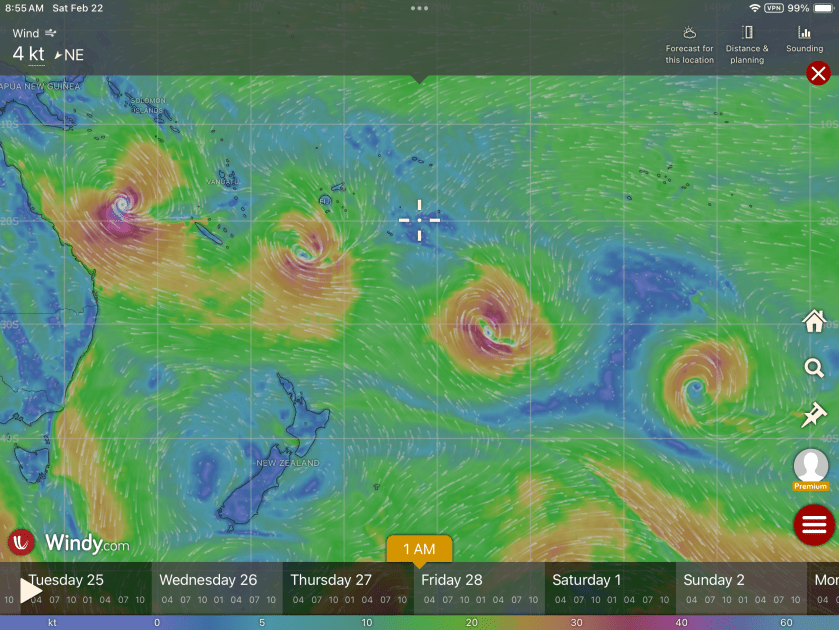

Finally, we decided it was time. Not only to raise anchor at our current location, but to move on in general. There were only two days remaining in the month of April. We had spent two weeks in Wallis without even a raised eyebrow regarding potential bad weather. Cyclone season was at the brink of ending and we had been looking forward to reaching Fiji for over a year.

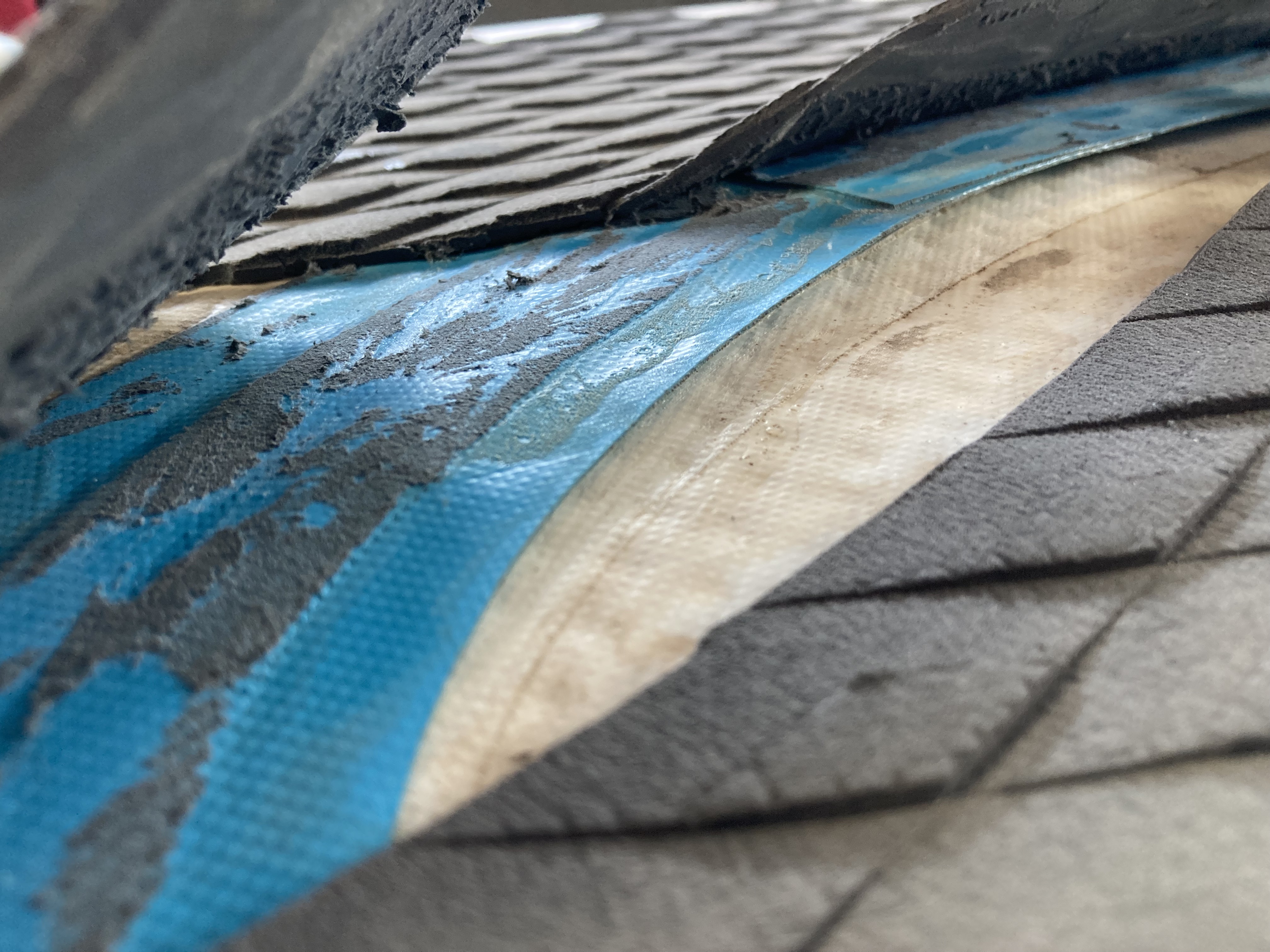

We returned to anchor at Íle Fungalei, where we were only a mile from the town and could finish any last minute provisioning before setting out. We had hoped it might be possible to fill our three propane tanks in Wallis, one which was completely empty and two which were down to fumes. However, just as in Tuvalu, the fittings that connect to the tank for filling were not compatible with our tanks. Even our attempt to gravity fill the tank in Tuvalu had not worked. We then learned that there was a larger industrial propane facility at the south end of the island that could possibly help us out.

Thankfully, the immigrations and customs officials were more than happy to allow us to go through our clearing out process a few days in advance with the understanding that we would be stopping down there before actually departing Wallis. This is not typical, as often times a boat is expected to depart immediately after the clearing out process has been completed. Even a twenty-four hour grace period is unusual.

We finished our final preparations and prepared to clear out.

During some last minute provisioning, I discovered a magical sandwich in one of the grocery stores, loaded with French fries. I had first gotten hooked on fish sandwiches laced with French fries in Moorea, French Polynesia over twenty years ago. This one was chicken, but the memory still got me salivating.

There was no way this sandwich was ever going to make it back to the boat. I proceeded to scarf half of it next to the Wallis post office. The other half only made it a couple hundred yards further. As good as it was, I couldn’t resist the pleading eyes of a very friendly dog who also seemed to find the sandwich irresistible. We finished the other half just off the causeway before returning to our dinghy with our last load of provisions. Mmmmmm.

Aside from our quick detour to Halalo with the hopes of getting either propane or butane into our tanks, we had only to clear out officially with the authorities.

The customs office right there at the end of the causeway was easy enough to deal with; the immigration officials arrived in a vehicle, saving us an extended walk, and stamped our passports right on the bench outside the customs office. Easy enough.

Regrettably, the propane/butane fill turned out not nearly so simple. We struck out again at the Halalo facility. Shit outta luck. No compatible fittings. All we could do was hope we had another few days worth of cooking gas left in the tank.

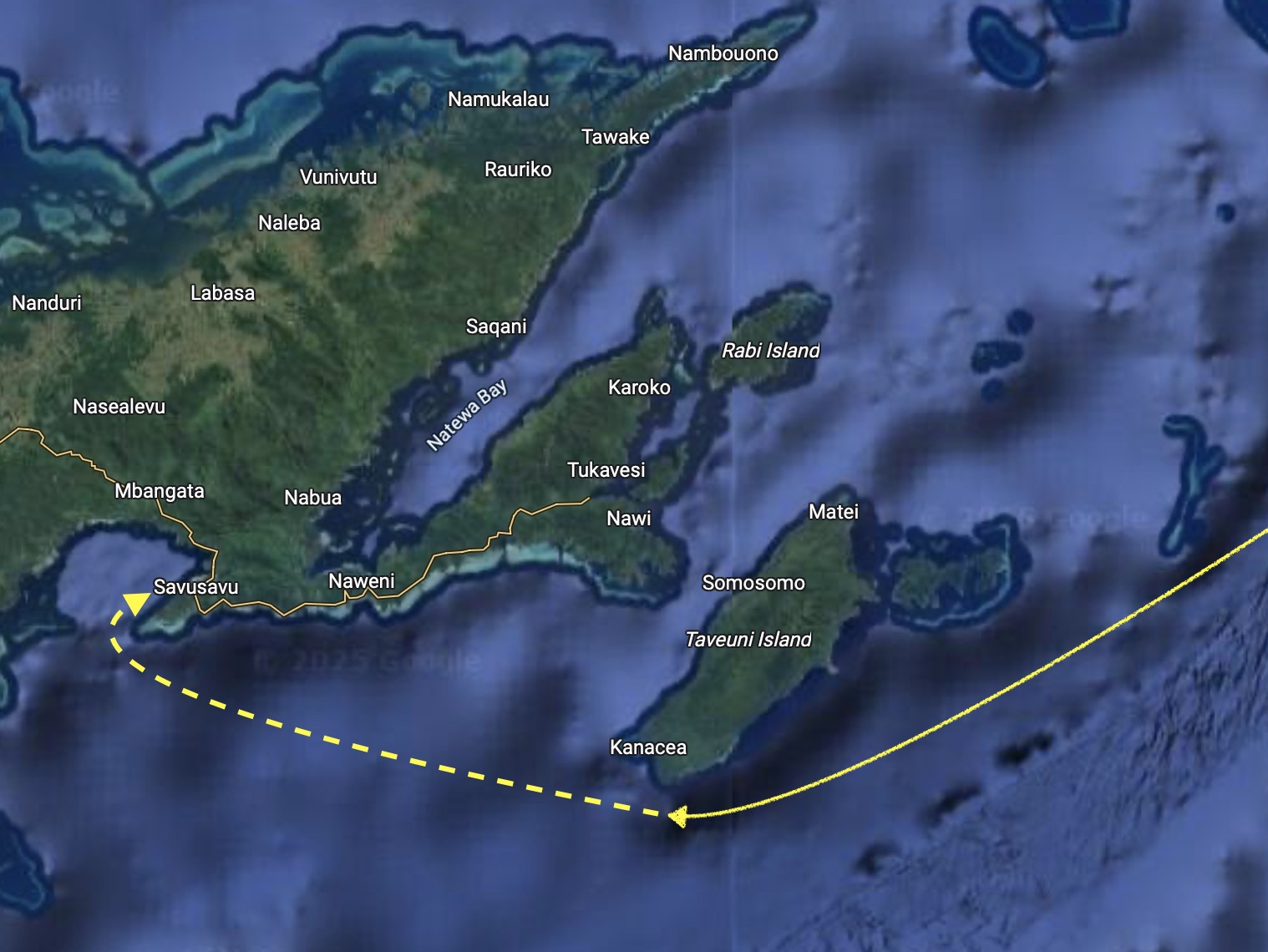

There was close to four hundred nautical miles separating us from Savusavu, Fiji where we would need to clear in. About three days time, if all went well.

We expected mostly fifteen to twenty knot winds with some potential squalls but nothing too nasty. A bit sporty maybe. And there would be no full moon as we had seen between Tuvalu and Wallis. In fact, only a sliver of a crescent moon, so we’d either get a great show of stars or disconcerting blackness.

If you’re Steve…how do you celebrate the finale of a brilliant return visit to Wallis? But of course – a bacon sandwich to build up strength for the process of getting underway…

…followed by BBQ ribs at sea. We had never hauled out the barbecue while actually underway before our passage from Tuvalu to Wallis. Now it seemed as though it may be turning into a bit of ritual or tradition. Oh dear…

That evening, a calm sunset under sail seemed to reflect a good omen of a smooth passage to come. Hopefully, both Neptune and Poseidon would be in agreement.

As it turned out…maybe not entirely.

Our first night turned out bouncy and uncomfortable. Not too wet but constantly threatening squalls loomed all around us. As well, the sea state had not been unreasonable, with only about six or seven foot swells; but the short interval between waves, directly on our beam, had made things much less pleasant. Throughout a pitch black night, we had been sailing with a double reefed main and only a scrap of solent sail unfurled. We welcomed the first light of the coming morning.

However, the dawn also revealed a rather foreboding cloud bank on the horizon, so dark it seemed to actually create a barrier between the morning sun and the water beneath it.

Though the sun’s golden glow slowly forced its way underneath the harsh line of the cloud’s black underbelly, the cloud itself remained an ominous gray as it quickly bore down on us from behind.

Within fifteen minutes, the cloud bank passed directly overhead, and a vicious squall dumped what seemed like wheelbarrow loads of rain on top of us. Our boat speed, which had been a meager three knots at the time, instantly jumped to over nine knots as forty knot winds whipped up. Thankfully, we had seen the menacing clouds in the distance, and had not put up more sails at first light. We altered course so we were running dead downwind with the squall. For a time, it was a hell of a ride. Still, fortunately no damage was incurred.

Twelve hours later, we reflected back on a day that had started with absolute chaos but eventually settled into a rolly though chilled out day without additional drama.

The second evening, by comparison, was a brilliant night of sailing: consistent winds, good conditions, no squalls, magnificent starry skies, and no motoring. To top it off, we each got a comfortable and sound six hours of sleep.

Depending on conditions, circumstances and sometimes events, our night watches are typically four hours on, four hours off. A short watch (say, only two hours) is nice for the person on watch, but unfortunately means a meager rest for the person who is off. A couple of hours of sleep is rarely satisfying or rejuvenating, especially while on passage. It’s always a trade off.

In great conditions, the long watch doesn’t seem so significant and the other person gets a solid rest…the best situation you can hope for.

Midafternoon on May 4 we had been underway for forty-eight hours. With less than one hundred nautical miles remaining before arriving at Savusavu, Fiji, where we would clear in, we sailed past our first Fijian island. Fiji is ultra strict regarding boats not visiting an island or even anchoring in a bay before completing the official clearing in process. Violating this restriction is basically begging for a lot of grief, or even grounds for being either refused entry or immediately deported. We were content to only take photo as we passed by from a distance and keep sailing on.

As night approached, we began constantly calculating our speed against the distance remaining, hoping to time our arrival at Savusavu to coincide with the light of day.

At exactly 21:12 we crossed 17°S latitude / 180° longitude. Though the actual calendar date adjustment for the international date line in this area occurs east of 180° and we were already a day ahead of those on the other side, it was still noteworthy that we were, at that moment, on exactly the opposite side of the Earth from the prime meridian and 0° longitude in Greenwich, England.

By 9:30pm, we were coming around the southern tip of Taveuni, approximately fifty nautical miles out from the marina. With about eight hours until sunrise, our timing would be perfect if we kept under six knots of speed. Since our average speed is typically closer to five knots, it seemed like a done deal.

The reality was, I don’t think we have ever had so much difficulty maintaining less than six knots. In fact, it seemed, even with the main sail still double reefed and the solent sail nearly entirely furled in, we were having trouble staying under even seven knots of speed. Inconveniently efficient, I guess. Go figure.

Our speed eventually slowed overnight and, by 6:00am, we were approaching the final point separating us from Savusavu Bay. Behind us, the skies above Taveuni Island looked as though they were on fire as the sun rose above the horizon line.

Two hours later we dropped the main sail and motored into Nakama Creek, just off of Savusavu.

A short time after that we were tied up on the clearance dock of Nawi Marina, where we were visited by a continually shifting entourage of smiling immigration, customs, and bio-security officials.

After a four hour process of waiting, then filling out various documents, then waiting for the next group of officials to arrive with more documents, the task of clearing in was complete.

Thirty minutes later Exit was secure in slip #16 and the end of pier #2. And while she may not have been as happy tethered to the dock cleats by a half dozen lines, we were ecstatic.

It had been exactly one year and four days since we had raised anchor and departed from Mexico…8,084 nautical miles travelled, stopping in 83 different locations across five countries. Nine and a half weeks (over 1600 hours) of that spent with the anchor up. A total of nearly 25,000 nautical miles over almost eight years aboard Exit.

And now, we had made it to Fiji.