November 6 – 25, 2024

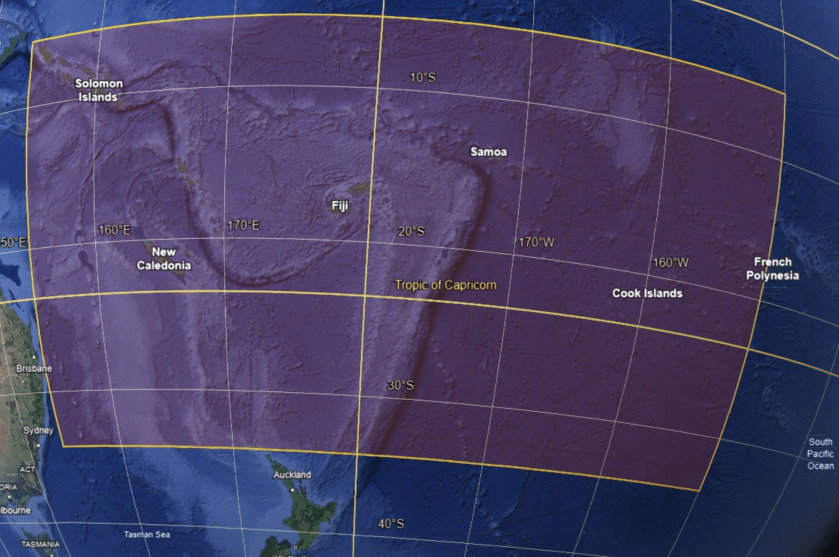

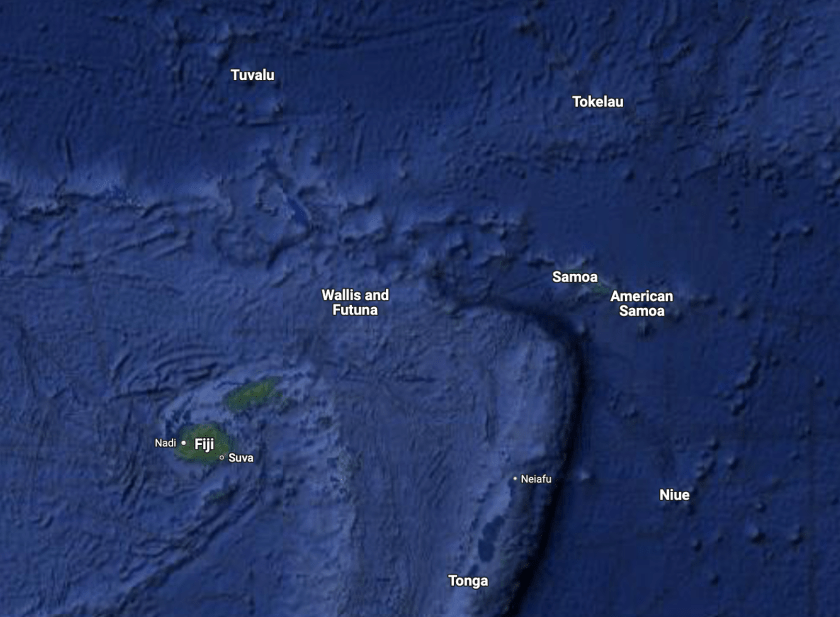

From a latitude of 19°S in Vava’u, Tonga to 13°S. We had travelled roughly 370 nautical miles. To a tiny oval shaped atoll, only about 13nm long from top to bottom with an 8nm long island inside.

It provided our first refuge for Exit while sailing towards our latitude 10°N “safe zone” outside the cyclone box designated by our insurance company.

Wallis and Futuna, a country made up of two island groups (oddly enough, one atoll Wallis and the other Futuna, which is actually comprised of two islands) which lie approximately one hundred twenty nautical miles apart. Its truly Polynesian heritage has ancestry tying back to both Tonga and Samoa, though it was briefly occupied by US troops during WWII and officially became an overseas territory of France in 1959. The entire country’s population numbers only about 12,000, approximately two-thirds of which live on Wallis.

Regarding the location of Wallis and Futuna, off the beaten path would be a comical understatement. Though there is an airstrip on Wallis, visitors number only about 3,700 annually, and I would imagine a significant portion of those must be relatives of some sort. Very few sailboats pass by and even fewer stop. Unlike other Pacific islands that see hundreds or even thousands of sailboats a year, Wallis and Futuna count visiting yachts only in the dozens.

Speaking neither Polynesian nor French, the two primary spoken languages on the island, we knew communication could be a bit of an issue for us. We had already learned this in French Polynesia. A great deal of the population speaks no English at all, and even those that do sometimes don’t let on until the last sentence or two of an exchange.

For us, the process of clearing out in Tonga had turned out to be far more stressful than the passage that followed.

In order to clear out, it had been necessary to bring Exit to the main dock in Vava’u. Our approach to the intimidating cement dock (with its submerged wreck at one end, rusty rebar sticking out, and nasty overhang that tried to suck our toe rail underneath it when we cleared in) was made even more ominous by fifteen knot winds that pushed right at the dock. Moreover, the dock was already stuffed full of sailboats, already rafted two-deep in a couple of spots.

As we passed slowly by, trying to assess the situation, an older guy on the only sailboat that didn’t already have another boat rafted to it, yelled over that we could raft up to him if we wanted. Normally, this would be something we would try to avoid in any way possible, but we didn’t see much of an alternative. We had no idea how long everyone was going to be, so we yelled back that we’d come around a second time to try. At least this would put a bumper between us and the cement dock.

We circled around, allowing Kris to bring us in close enough to throw a line but not so close that we would end up side-swiping the guy. It was perfect. We had about ten feet between us when I got our bow line in the guys hands. Except with fifteen knots of wind, as soon as we stopped moving forward the bow started drifting towards the boat. Fast. The stern was barely moving which meant suddenly our anchor, jutting out from the bow roller, was going to make contact far before the fenders that were hanging off the port side.

It looked like a disaster was imminent. I was already envisioning our seventy three pound Rocna anchor gouging a deep line into the fiberglass hull of the sailboat we now were only about two feet away from. The guy on the other boat had already moved astern to try to grab a line from Kris, so I was the only person nearby.

There was no way Kris could power away from the boat; gunning the engine would have just rammed us into the side of the guy. There wasn’t time to reposition the fenders. There was only about three seconds left before our anchor was going to start deconstructing his hull. Seeing no alternative, I jumped over our lifeline and put myself between the two boats, hoping I could push off, and stop the bow from drifting closer without becoming a fender myself. It was one of those moments – push with everything you’ve got plus a little bit more, or have something crushed between two gigantic objects each weighing multiple tons.

Somehow…the anchor stopped with only about three inches separating it from the other sailboat, and I managed to avoid being in between the two. As the stern slowly drifted in, the fenders hanging alongside our hull were the only things that made contact.

I could feel my heart start beating again as I breathed out. I was pretty sure I hadn’t actually shit myself, but I wasn’t absolutely certain for a minute or two. Jesus Christ! That was close.

Soon after we were adequately tied to S/V Shandon, the sailboat we had nearly given a face lift to, we learned that the Customs Officer was off island.

Shit.

And he had the required customs stamp in his possession.

Seriously?

However, he was about to land at the airport and would be here before long.

Okay. Not a fiasco.

As it turned out, when a white pickup with ‘CUSTOMS‘ in big green letters on the door of the truck pulled up and stopped at the edge of the dock, we learned it wasn’t just the customs officer who had been returning on the plane. He opened his door, stepped out, walked around to the back of the truck, dropped the tailgate, and opened the wire door of a plastic kennel sitting in back. Out jumped Tonga’s new canine customs agent.

Once the customs officer concluded we were not smuggling drugs, weapons, or any other contraband, the remainder of the clearing out process went rather smoothly. Eventually, we had our paperwork and passport stamps in hand.

Getting back off the dock was another matter entirely. Only after lowering our dinghy into the water, with the assistance of our friends aboard S/V Solstice Tide and their dinghy as well, were we finally managed to get clear of the sailboat we had been rafted up to. It required a simultaneous push off by both dinghies at both Exit’s bow and stern.

Having successfully cleared out of Tonga, Exit departed Vava’u late in the afternoon on November 6. Perfect timing considering we were one day ahead of the U.S. which made it Election Day there. A good day to not be online.

Only twenty nautical miles north of Tonga we passed within five miles of the location a 2000 foot deep undersea volcano which had erupted in 2019. A bit scary to think about what would happen if history repeated itself here, but still not nearly as scary as the history that was about to repeat itself in the States.

Turning on Starlink to get a weather update turned out to be a big mistake when we glanced at the news and found out that the Trump Shitshow 2.0 and MAGA Zombie Parade was about to officially be scheduled for another four year season…great.

The sixty-seven hour passage from Tonga was a bit sporty at times but nothing dramatic. All the ominous forecasts that predicted huge deluges of rain dumping upon us turned out to be false alarms. To the contrary, we witnessed a stunning sunrise and enjoyed some bright blue skies and fantastic sailing.

Even our arrival to Wallis, which had threatened to be quite wet that morning, turned out to only be gray with a few drops. The crappy weather had very politely skirted around us, for which we were very grateful.

Despite having to acknowledge we had been pretty damn fortunate while underway, we couldn’t argue with the perspective our anchor beers relayed…

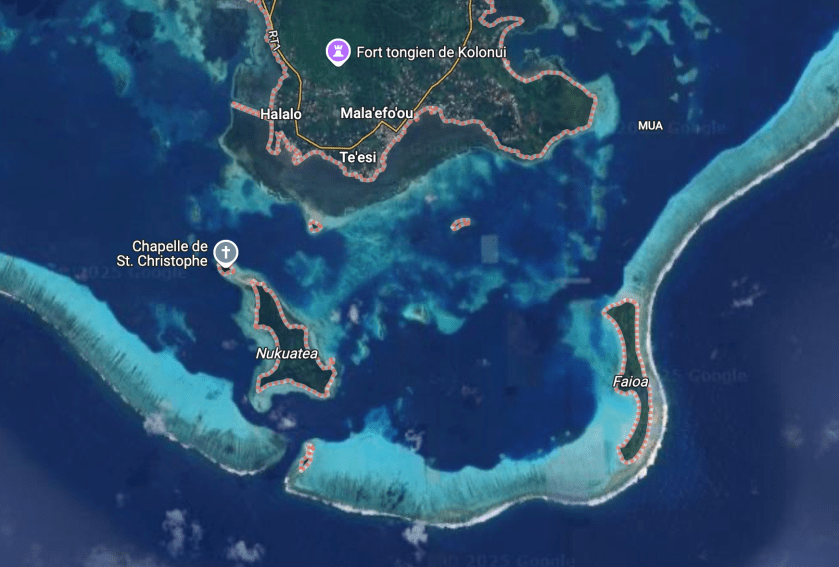

We had set anchor inside the atoll of Wallis on a Saturday just before noon. That evening we ended up enjoying a magical sunset at anchor just off a small uninhabited island named Île Faïoa in the southeast corner of the atoll while we awaited the arrival of Monday, when we thought we could clear in.

As it turned out, S/V Kuaka (who had departed Tonga a few days ahead of us) was already in Wallis and had cleared out the day before our arrival. They had left town the morning after we had come through the pass and ended up anchoring at Île Faïoa right next to us, awaiting better weather at the end of the weekend as they continued north to Kiribati.

It gave us an opportunity to see them once again, thank them again for first planting the idea of heading this way, as well as get timely and current information about the area we had just arrived at.

First thing Monday morning, we raised anchor and headed seven miles north to Mata-Utu, the main town and capital of about 8,000 people, where we would officially clear into Wallis and Futuna.

Clearing into the country, we had to delicately tiptoe our way through an interaction with a quite irritated police officer who would serve as our Immigration official. While we waited outside the port authority office, he had very aggressively pulled up in front of us in his marked police car and stepped out with his partner beside him. In full uniform, he was short and stocky with a tiny tuft of hair at the front of an otherwise shaved head. He spoke English very well. He was not happy. Today was Monday. We had arrived on Saturday. Why had we not already visited them?

We politely explained to him that, after attempting to hail the port control authorities on our VHF radio and getting no response two days prior as we were passing through the entrance channel, we had concluded that they were closed for the weekend (not an uncommon situation in some places). We had then dropped anchor just off a nearby island, raised our yellow “Q” flag (an indication that we had not yet cleared into the country), and remained on the boat for the weekend. First thing Monday, we sailed the nine miles to town and came directly to the port authority office where we had been awaiting his arrival for three hours. We profusely apologized for anything improper we had done and expressed that we were trying our best to follow the correct protocol.

After sternly reprimanding us for not coming directly to the town and visiting the police station immediately – an offense we were informed could result in us being told to leave immediately – he ended up stamping our passports, shaking our hands, and smiling. Whew!

Subsequently, when we preemptively apologized to the Customs Officer inside the nearby office, he gave a bit of a smirk and said something along the lines of, “that’s just him.” Filling out the customs paperwork, I misinterpreted one of the blank spaces at the top of the document. When I handed it back to the customs official, he looked it over and promptly said, “Oh…no, no…”, while crossing out the date I had written in the blank. Still gunshy from the Immigration official, I immediately grimaced, wondering what we’d done wrong now. He walked across the room, checked a big three-ring binder, walked back over and wrote something above the date that he had just crossed out. I looked and it was the number “35”.

He looked at us, smiled, and told us we were the thirty-fifth sailboat to visit during 2024. We returned the smile and started breathing again.

Once we had cleared in, even with the language barrier we found people unbelievably friendly. Walking along the roadside, almost everyone waved and smiled at us as they passed by. We laughed at how ridiculous you would be received in the U.S. waving at every passing car…oh ya, you’d be ignored or looked at as the homeless person seeking a handout.

We learned quickly that weather conditions here could shift very rapidly. A brutally hot day with nothing but sunshine and puffy clouds was apt to be offset by a downpour at any time.

Just standing on the causeway, we could experience the gamut of changing weather.

A deceptively fast moving squall drifting toward us turned out to be a nearly daily occurrence, oftentimes multiple times in a day.

This one turned out to be a pretty modest amount of rain. Not always the case though.

We soon learned it could be a bit challenging to coordinate our time in town. Winds and/or ran might make for a difficult trip in to town or back to the boat; or the incessant heat of a relentless sun beating down could make walking around an exhausting affair. Even if the weather cooperated, we often found we had arrived in town before anything was open, or during the afternoon when things seemed to close as well, or it was too late for us to risk having to make our dinghy commute after dark.

We couldn’t tell if this time of the year was outside of any kind of a tourist season…or whether that even existed here.

After having a bit of a wander about the town, we decided to head back south to the small island of Nukuatea, on the opposite side of the pass that the island we had anchored at upon first arriving at Wallis was.

Once we had settled in at Nukuatea and appeared to have a fair weather window of opportunity with no squalls or deluges emanate, we decided on a trip up the mast.

Not an emergency; just necessary for an inspection of everything – both to check on any potential issues that had developed during the previous passage as well as for peace of mind before commencing on our next passage. As is usually the case, it provided a great vantage point.

Fortunately, it turned out one didn’t need to be at the top of the mast for an excellent view. Whether it be an afternoon rainbow…

Or another brilliant sunset…

As Polynesians Islanders, the inhabitants of Wallis have an obvious historical tie to the ocean with an incredible lineage of nautical navigation and mariner skill. During our stay, we had the pleasure of witnessing their fascinating traditional sailing outriggers gracefully plying about the lagoon inside the atoll.

Soon after, we learned there was a dive shop on the island. It was owned and run by a French expat named Pascal who had moved to Wallis twenty three years ago. We stopped by his tiny shop – more of a hut, complete with equipment hangers made literally from sticks – and signed up to join a dive already scheduled for the following day in one of the passes.

When we arrived the following morning three other divers, very chatty and friendly French expats who spoke perfect English were there also. Because they were quite inexperienced, the plan had been for Pascal to take the three while we accompanied another dive instructor who was familiar with the pass. Unfortunately, the instructor was sick and wouldn’t be coming along.

No worries. We were used to diving alone; and after a thorough briefing felt completely comfortable with the situation. As it turned out, when the dive boat arrived at the pass, the current was outgoing and it was absolutely ripping. The call was quickly made to alter the plan, and we all headed outside the pass in the dive boat to a spot on the outer side of the atoll. Pascal said we were still free to go on our own. Despite having very little information about where we were going, we hopped in the water and had a great dive wandering randomly amongst underwater canyons. We had a surface marker to deploy at the end of the dive so, without meandering too far or doing anything silly, we were confident knowing there was a boat to pick us up when we surfaced. It wouldn’t make the list of best dives ever; regardless, we had an awesome time doing our first solo dive on the outside of a remote atoll in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Among the many things we have learned living aboard Exit for the past eight years, one of those is the fact that everything takes about five times longer to do on a boat than it would otherwise. Another is that we have friends all over the world; we just haven’t met them all yet. Case in point…

Our next mission was to secure diesel and gasoline for Exit’s reserve jerry cans. Ironically, this turned out much more challenging than our earlier dive had been.

The typical procedure is to go ashore in our dinghy, walk to the nearest gas station with empty five-gallon jerry cans, fill them with either diesel or petrol, then haul them back to the dinghy in our wagon, repeating the process as many times as is needed to fill tanks or top up our reserves.

It’s no red metal toy wagon. Rather, more of a utility cart – blue canvas covering a metal frame that folds up for storage with swiveling front wheels and a 150 pound load capacity… maybe we should call it the “Bluetooth Hauler” as a tip of the hat to the old classic “Radio Flyer”…hmmmm.

Anyhoo…

Google Maps had identified a “gas depot” just over a mile from the dive shop. We tied up the dinghy at the dock next to the dive shop and proceeded to walk casually down the road toward the gas station, immediately realizing we had opted to undertake this task in the excruciating heat of a relentless midday sun. After walking for what seemed like more than the anticipated distance without seeing a filling station, we decided to check GoogleMaps on Kris’ iPhone, only to discover it was now behind us!

Confused, we turned around and started backtracking, this time paying much closer attention to GoogleMaps. When we arrived at the supposed location, we looked around quite perplexed and were quickly dismayed to see off the road, tucked away behind a fence, a small yard that contained dozens and dozens of stacked portable propane tanks. We had obviously misunderstood the nature of the business identified as a “gas depot”. Cooking gas…not engine fuel.

Fuck.

Amazingly, we were only a hundred or so yards from a small brewery we had walked past earlier. We were hot, frustrated, and still without fuel. Sweating buckets and completely parched, we immediately decided to drown our misfortunes in a couple of bottles of locally brewed beer.

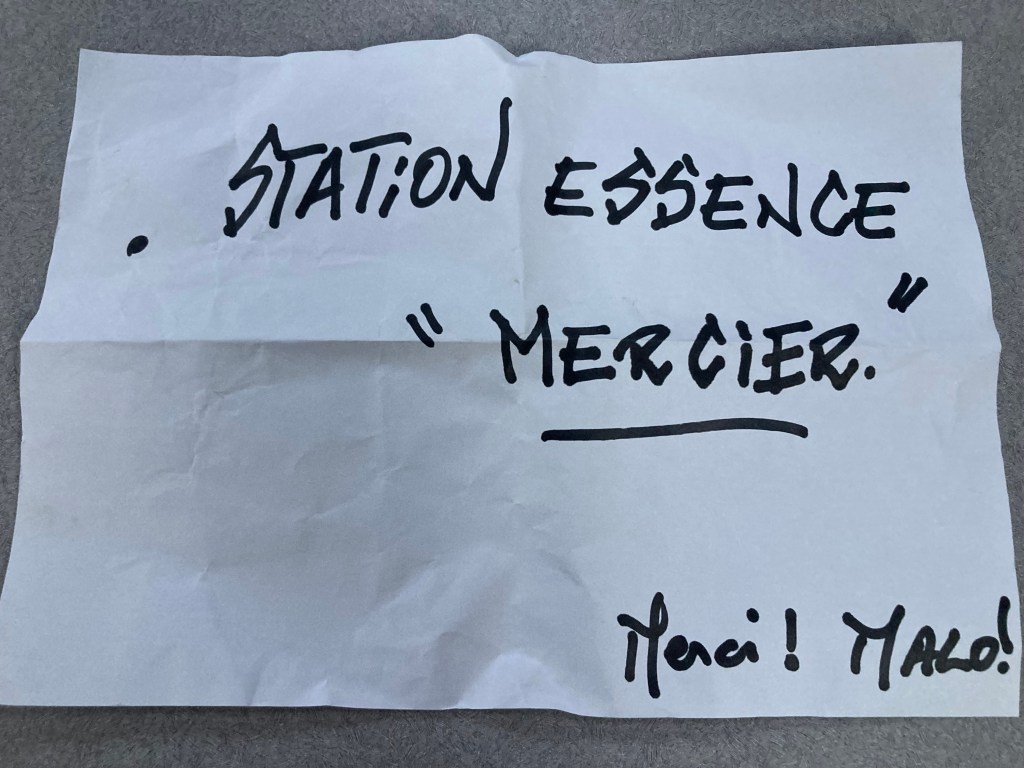

Inside we met Serge, the French proprietor who spoke absolutely zero English. After we had two glasses of semi-cool beer in hand (the brewery didn’t officially start serving for three more hours), a great deal of gesturing, attempted use of Spanish as a somewhat intermediary language, and references to the props we carried in the wagon (fuel jerry cans) allowed us to convey the essence of our situation to him. While Serge relayed vast amounts of information back to us, all of which we had absolutely no idea what he was saying, he managed to communicate that the gas station we were seeking was actually a number of miles further up the road.

After finishing our beers and buying a variety pack of twelve more, Serge provided us a solution… a sheet of paper with a handwritten message in French: “Gas station please”. He pointed to the road out front, held up the sheet of paper, and stuck out a thumb. Brilliant.

After three or four cars drove by, the occupants all with confused looks, a scooter with two boys, maybe fifteen years old stopped next to us. They read the sheet a number of times and spoke to each other back and forth. Eventually they nodded their heads, only we couldn’t figure out what they were saying. We weren’t sure if they wanted us to give them money (which we didn’t know how much or whether they would even return), or how this could even work with four people and a wagon carrying jerry cans given they were on a scooter. After a lengthy back and forth exchange of words, gestures, and expressions that generated more confused looks on both sides, we were able to establish that they were going to go round up a car. We waited for about five minutes before they returned as passengers in a pickup that contained three of their friends and a driver who looked to be in his twenties. The driver signaled for us to hop in the back of the pickup. We did, and they proceeded to drive us to the gas station. All the while the three other kids sitting in the back with us asked questions in very broken English, smiled, and chuckled amongst themselves.

A few minutes later we were standing at the pumps getting our jerry cans filled. Afterwards they proceeded to give us a ride all the way back to our dinghy at the dive shop. What was nearly a maddening fiasco and afternoon of unproductive frustrating misery turned into an opportunity to meet new friends and experience the kindness and generosity of Wallis.

The episodic rains, which seem to be nearly a daily event, are the one thing that breaks up the withering tropical heat which also seems to be a staple of the island. Some momentary drizzles come and go quickly – “all seventeen drops” as we would refer to them. Others fall more under the category our friends on S/V Solstice Tide refer to as “biblical rains”.

Trying to keep an optimistic outlook, we had celebrated the fact that our rain catch was the best it had been for about as long as we could remember. Well, years for sure. The twenty two gallons of water jerry cans were completely full for laundry and even both of Exit’s one-hundred gallon water tanks had been pretty much topped up.

So far, throughout our explorations into the Pacific Ocean, we have had the good fortune of largely avoiding the electrical activity that often accompanies these wet occurrences. However, during one of these overnight biblical rain events, our luck ran out.

Early in the morning (after all, 2-4am is the typical time the shit hits the fan), as one particular deluge continued unabated, lightning flashes began bursting around us. The wind wasn’t unreasonable, and we were anchored in a hundred feet of water all by ourselves in a protected bay on the leeward side of a small island that had to be a couple hundred feet taller than our mast, so we weren’t exceptionally concerned or nervous. Any lightning is always disconcerting, but the thunder wasn’t exploding like bombs all around us in ways we had experienced in places like Panama, so we knew it wasn’t right on top of us. However, at one point, a pretty big blast kicked off.

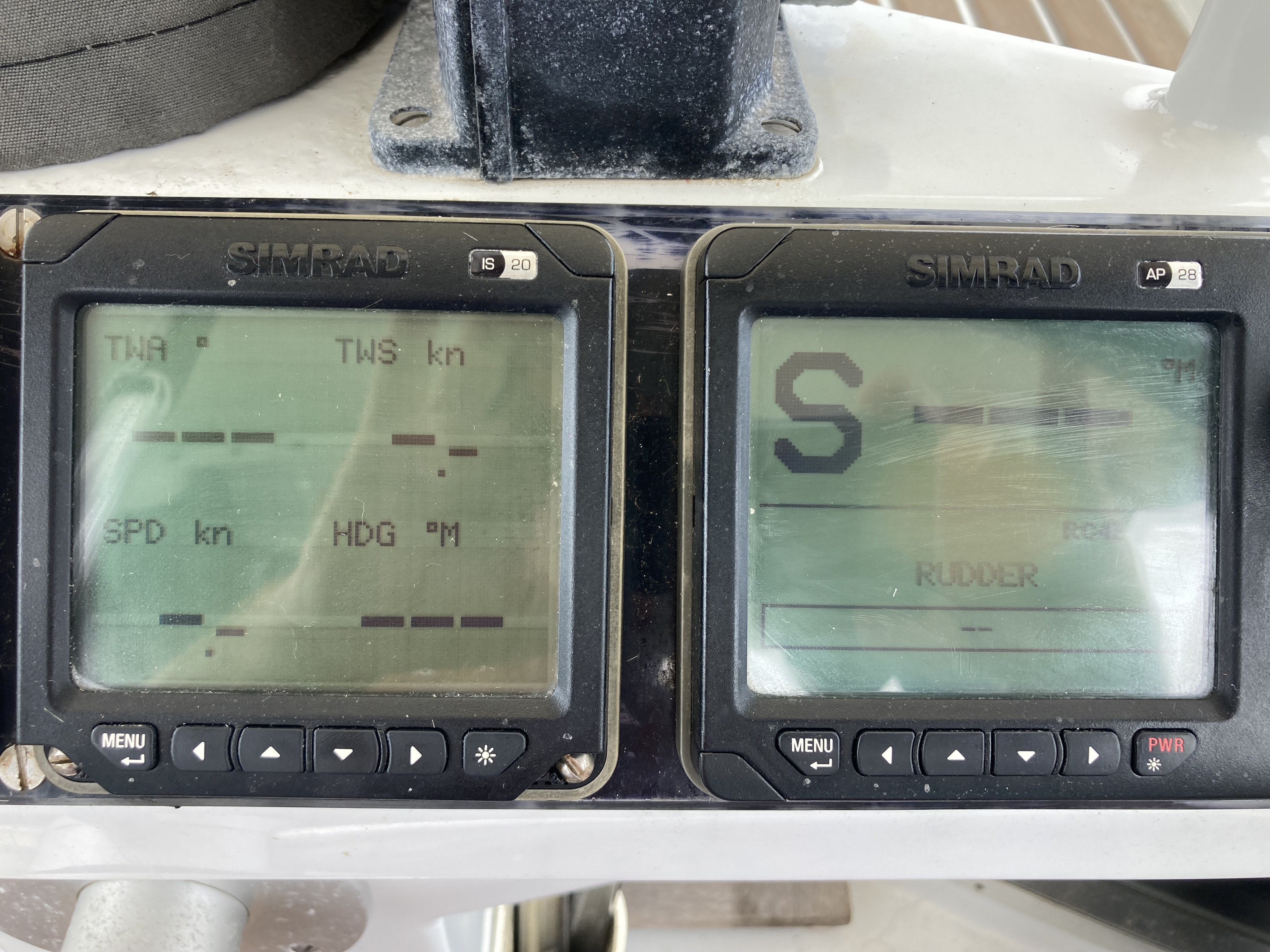

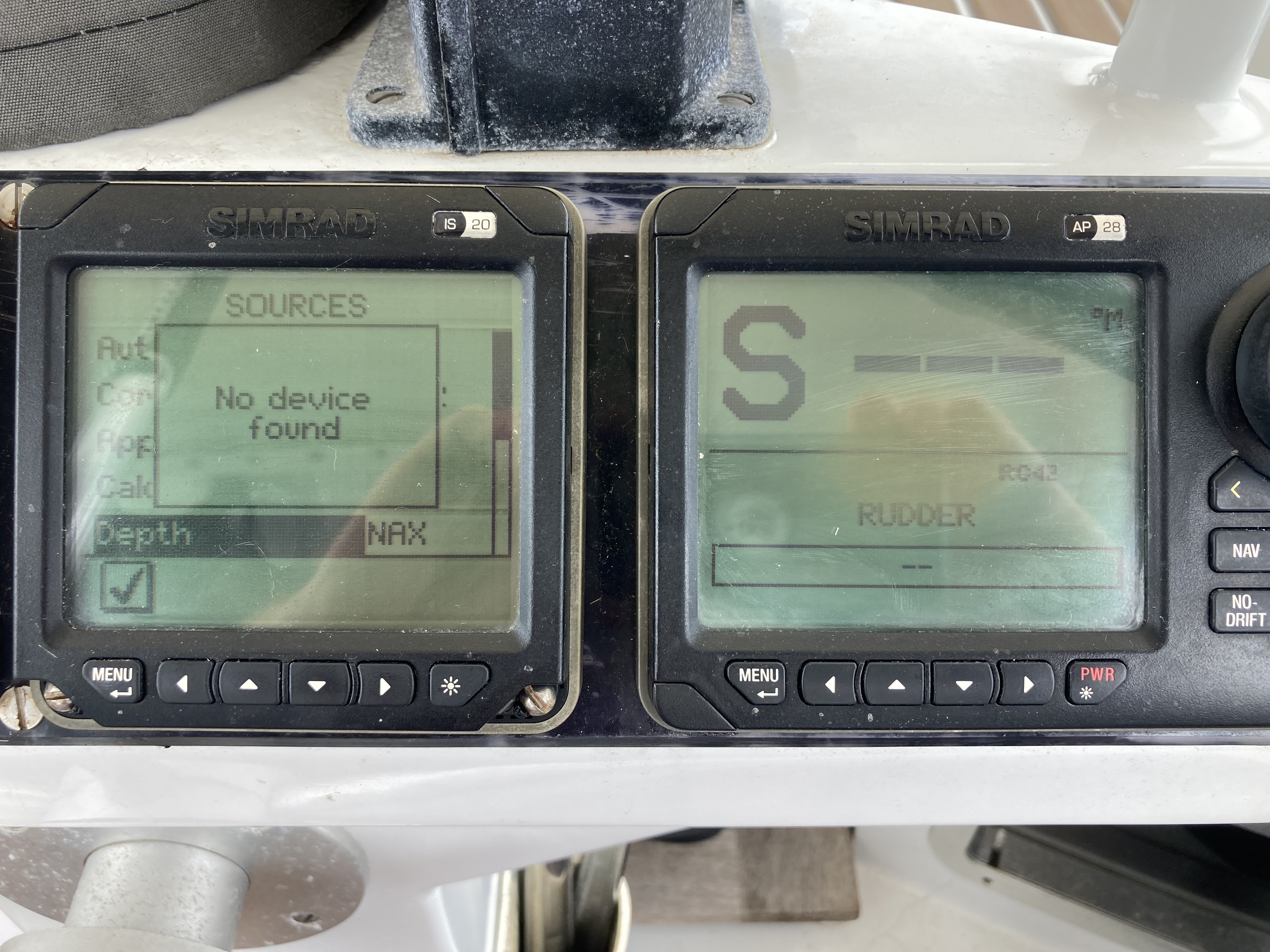

When I turned on the navigation electronics the following morning, a groan emanated from my mouth that was probably immediately chased after by a string of expletives. All of the data that would normally pop up on the displays as numbers came up as only dashes.

“- – – ”

Nothing more.

Shit.

No depth. No true wind speed or direction. No apparent wind speed or direction. No boat speed. No magnetic heading. Not on any of the six displays.

Furthermore, when we turned on the autopilot, the ominous message came up, “No Autopilot Detected”. Both displays (one at the nav table below decks and one at the helm) concurred.

Double shit.

We were still getting power to all of the navigation electronics, but no data readings. Starlink still powered up, and thankfully worked fine. The watermaker was still powered up with the display indicating all was good. The VHF, radar, and AIS systems were all good.

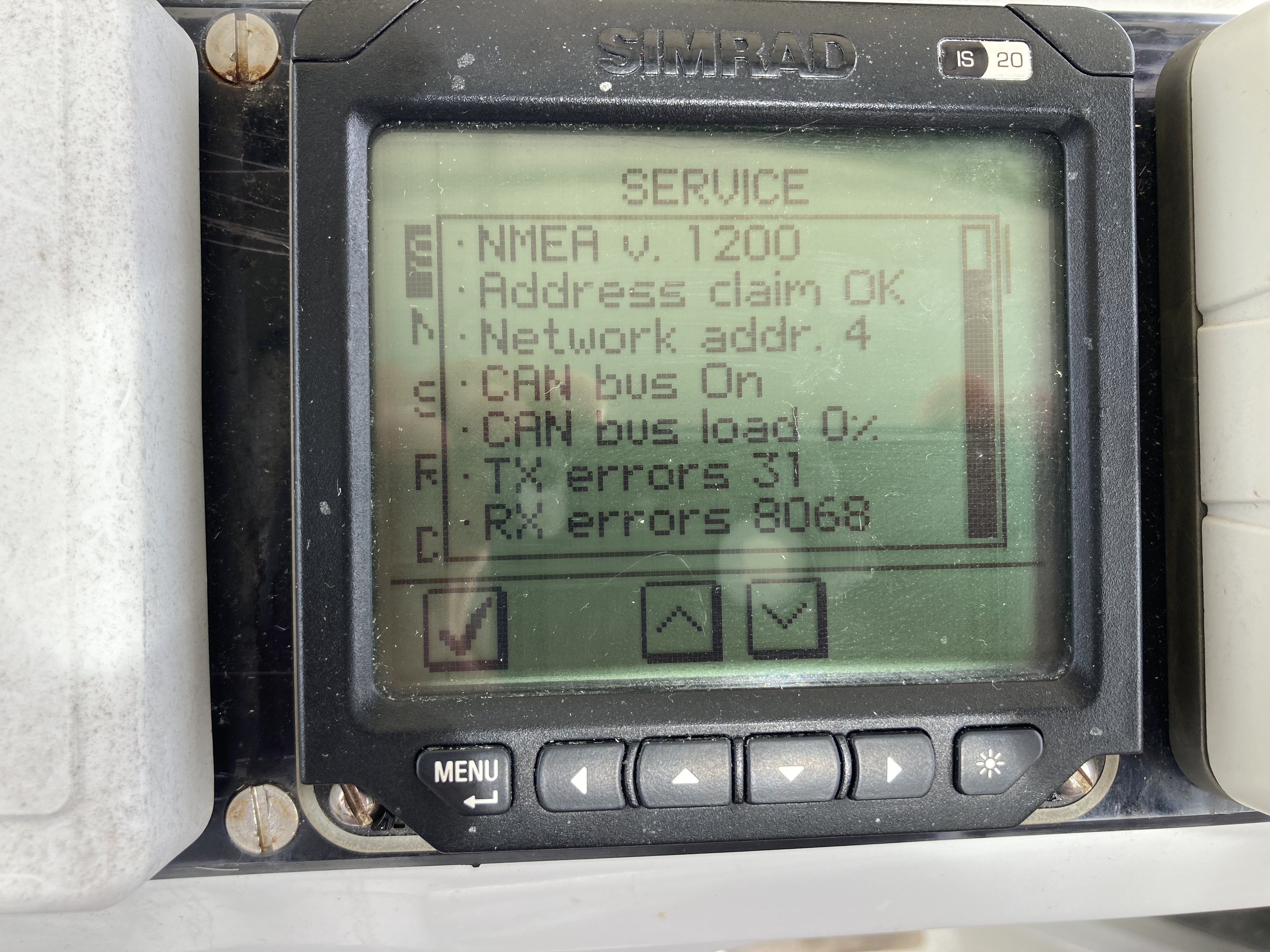

We came to the conclusion that there was no way we had received a direct lightning strike. There would have been much more catastrophic damage to the electrical systems. Our running theory was that some sort of an electrical static or electro-magnetic halo from close proximity lightning had done some serious voodoo shit to our systems, and one or more components in that network had either failed or been affected.

The reality was it was pretty academic. Didn’t really matter. At this point, it was about troubleshooting things and finding the source of the current issue, not the cause.

After day one, ten hours of tracking wiring routes, testing components, bypassing things, and attempting various options and possibilities got us nowhere. We were mentally exhausted, flummoxed, and no closer to a solution. No answers, no successes and lots of additional questions. We resolved ourselves to a morose happy hour and called it a day.

The following day, the black tunnel we found ourselves in began to reveal a dim light in the distance. We first got the magnetic compass reading to appear on one display. Success; tiny but undeniable. Additional troubleshooting began to eventually reveal other answers and slowly the complete fog of confusion began to dissipate. Other data began to appear on various displays at certain times under certain conditions. The autopilot began to see itself.

Without going into a long and boring breakdown of system details as well as the step by step drama which included endless re-routing, network isolating, and component testing, suffice to say we finally had almost everything back online by the end of the day. FUCK YA! By sundown we had determined that our wind sensor at the top of the mast was fried, as was an older electronic converter box that was no longer a necessity but had stuffed up the data communications by still being in the chain of things that were hooked together. The dead converter was bypassed and removed. An older wind sensor we still had as a backup could go back on the top of the mast.

That night, our happy hour was truly happy; victory tasted almost as sweet as the gin and tonics! Success had only followed in the wake of a long stretch of angst and frustration, but the confidence it built in our ultimate self-sufficiency and resourcefulness was palpable.

Two days later, we were rewarded for all our efforts with the realization we had both come down with some sort of nasty bug, probably during our human interactions on the day of diving, and found ourselves completely knocked out of commission for a handful of days. Victory celebrations are often fleeting.

This completely eliminated any motivation to get out and about for some well deserved exploration and play. Unfortunately, we had some hard decisions to make that couldn’t wait.

With only a week left of November, we knew we should be moving on. Yet Wallis was a fabulous place and we had only scratched the surface; we were seriously contemplating accepting to push our boundaries of good fortune by remaining a while longer. Except we’d been warned by another sailboat (S/V Queen Jane, who had been in this area twice before) that we needed to get going as favorable winds (or any winds at all) would soon become more and more scarce and turn more predominantly north.

If we could just make it to Tuvalu, a tiny cluster of nine islands four hundred nautical miles further northeast, we would be above ten degrees latitude, the threshold for still having a valid insurance policy. We could potentially wait out the cyclone season there and still have an option for returning to, not only Wallis, but also Tonga as well as Fiji. Tuvalu would be a primitive location regarding supplies; but if we pushed a thousand nautical miles further all the way to the Marshall Islands, a more tangible option for supplies and civilization in general, we would realistically be too far to consider returning. Tuvalu might keep all options still on the table.

It also wasn’t simply cyclone risks we needed to be aware of. The areas that can produce cyclones are just as likely to produce slightly less extinction level weather that can still be exceptionally problematic. Our recent electrical drama could be interpreted not only as an example, but also a bit of a warning omen.

We finally decided that if an apparent weather window opened up which afforded us the probability of sailing the entire way to Tuvalu, we would take it.

As an opportunity appeared on the forecast horizon and we decided departure was eminent, we picked up anchor and headed back to the main town to prepare for clearing out with the authorities, as well as provisioning at the supermarket – as much cheese, gin, tonic water, and wine (as well as less exotic priorities) that would fit in our lockers. If we were going to the edge of the world, we wanted to bring as much civilization as possible with us.

During our second day ashore, a barrage of rain began pounding down while we were in the supermarket. As we stood beside our “Bluetooth Hauler” wagon piled high with groceries under the supermarket’s awning awaiting a lull, we were approached by a couple with a young child. Though they spoke no English, they were able to convey an offer for a ride. We graciously accepted.

And, though we had avoided getting thoroughly drenched on the way back to the dinghy due to the kindness of locals, there was no getting around the one mile dinghy ride back to Exit.

It was though Mother Nature laughed and said, “Hah…do you really think you can out-maneuver me?” As we guided the dinghy away from the ship dock, another biblical rain commenced with twenty knot winds that pitched us all around. The ensuing waves and spray tossed what seemed like buckets of salt water on us. We arrived back at Exit looking like a couple of drowned cats, but with an another dinghy full of provisions that had amazingly remained mostly dry wrapped under a tarp.

The following day during our final journey to the supermarket, instead of rain we were assaulted by the oppressive heat of a brutal sun that had our clothes almost equally soaked, with sweat this time. Along the way, a man driving by veered to the side of the road, stopped, and started speaking to us in French. When we indicated we spoke no French, he repeatedly motioned for us to get in his car, which we did. As he fired up the car’s air conditioning, we learned his name was Olivier (as in Lawrence…). When we arrived at the supermarket, in true “Wallis form”, he gestured that he would do some quick shopping, meet us back at the car, and give a ride back to the dock. He even left the car running with the air-con on, in case we got back first!

We were so touched by his kindness, we bought him a box of fresh chocolate chip cookies and handed them to him after he helped unload the groceries from the back of his car at the dock. Briefly, he tried to refuse them. But when we insisted, he smiled, momentarily returned to his car, and climbed back out holding a gift of his own…a beautiful handwoven fan!

As Olivier drove away, we stepped into the Customs office, filled out our clearing out documents and received the official stamp. While we waited for the Immigration officer to drive down from the police station, the Customs officer, Bosco, made a truly valiant effort to fill what could otherwise have been awkward silence, with a barrage of friendly questions, struggling to communicate to us in broken English, supplementing his limited vocabulary with a flurry of finger tapping on his phone. No doubt, thanks Google Translate!

To our relief, the Immigration officer that arrived in short order was not the same person we cleared in with. This time the exchange was as pleasant as we could ask for and, moments later, we were returning to Exit with completed official paperwork in hand and a dinghy full of the final provisions we had collected.

It was crazy to think that, thirty days ago, we had never even heard of the country of Wallis and Futuna. Now, after sailing over six thousand six hundred nautical miles in the Pacific Ocean since departing Mexico seven months ago, it had taken only fourteen days here to conclude we had truly discovered a gem in the middle of nowhere. If possible, we fully intend to return.

But for now, it is time to continue onward.

If all goes according to plan, the next time we drop anchor will be above the latitude of ten degrees south on the other side of the International Date Line, which lies at 180 degrees, where our longitude will change from west to east. Our destination is a cluster of nine tiny atolls that make up Tuvalu, which has the unique title of being the least visited country on the planet.

It is not goodbye we say to Wallis; rather, until next time.