August 24 – September 21, 2024

We had already completed clearing out of French Polynesia, gotten our passport stamps, and picked up all of our paperwork from the authorities in Huahine. We had three days remaining to depart French Polynesia.

This was one of the few places we had visited that would allow you to stay more than twenty four hours after clearing out. Some countries expected you to return to your boat, lift anchor, and be gone. Here we were allowed to take care of all the paperwork a few days in advance and get the passports stamped with a future date.

Because there were limited locations that even were possible to clear out from, it was not uncommon here in French Polynesia for boats to stop at one of the outlying islands after clearing out and end up exceeding their allowed time. Cheeky, to say the least. Completely intentional. Another example of assholes willing to disregard the law, willing to push the boundaries for their own convenience and personal schedule, and give everyone a bad reputation.

On more than one occasion, we had heard of boats doing this with the backup plan of pleading that they had some sort of mechanical problem if they were actually caught. Our own perspective was that sailors who lied about engine failure or some kind of serious boat problem as an excuse to break the immigration laws and overstay their visas were begging Fate to step in and actually impose that very problem upon them at some time in the not so distant future. The well-deserved justice of self-imposed Karma…

We had no desire to engage in such fuckery.

Despite our disappointment, we had no intention of stopping on the sly at Bora-Bora, or further along at Maupiti as was even more common, to discreetly and illegally hang out as we passed by.

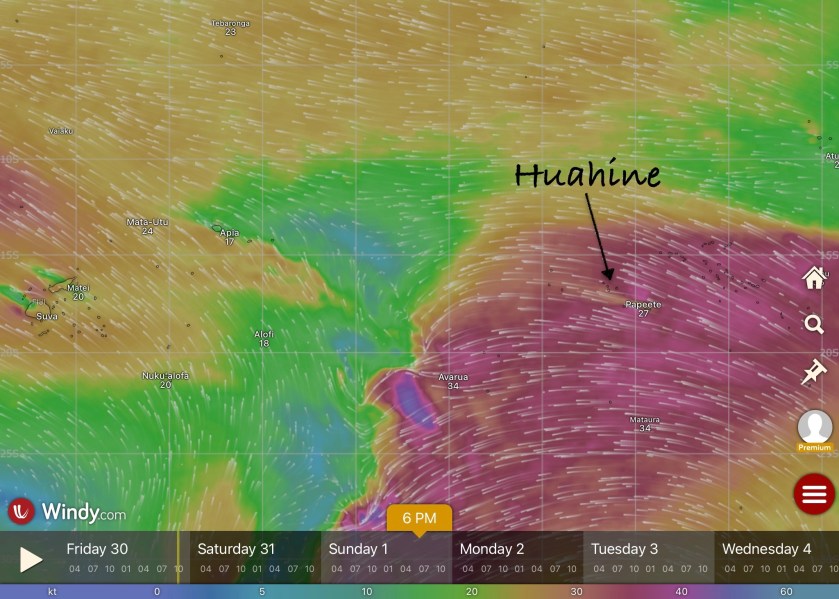

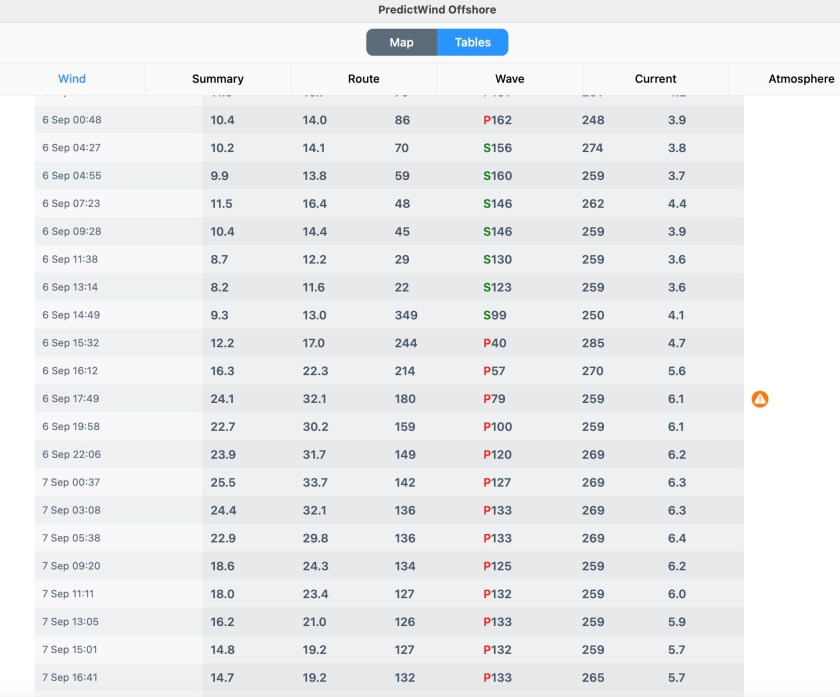

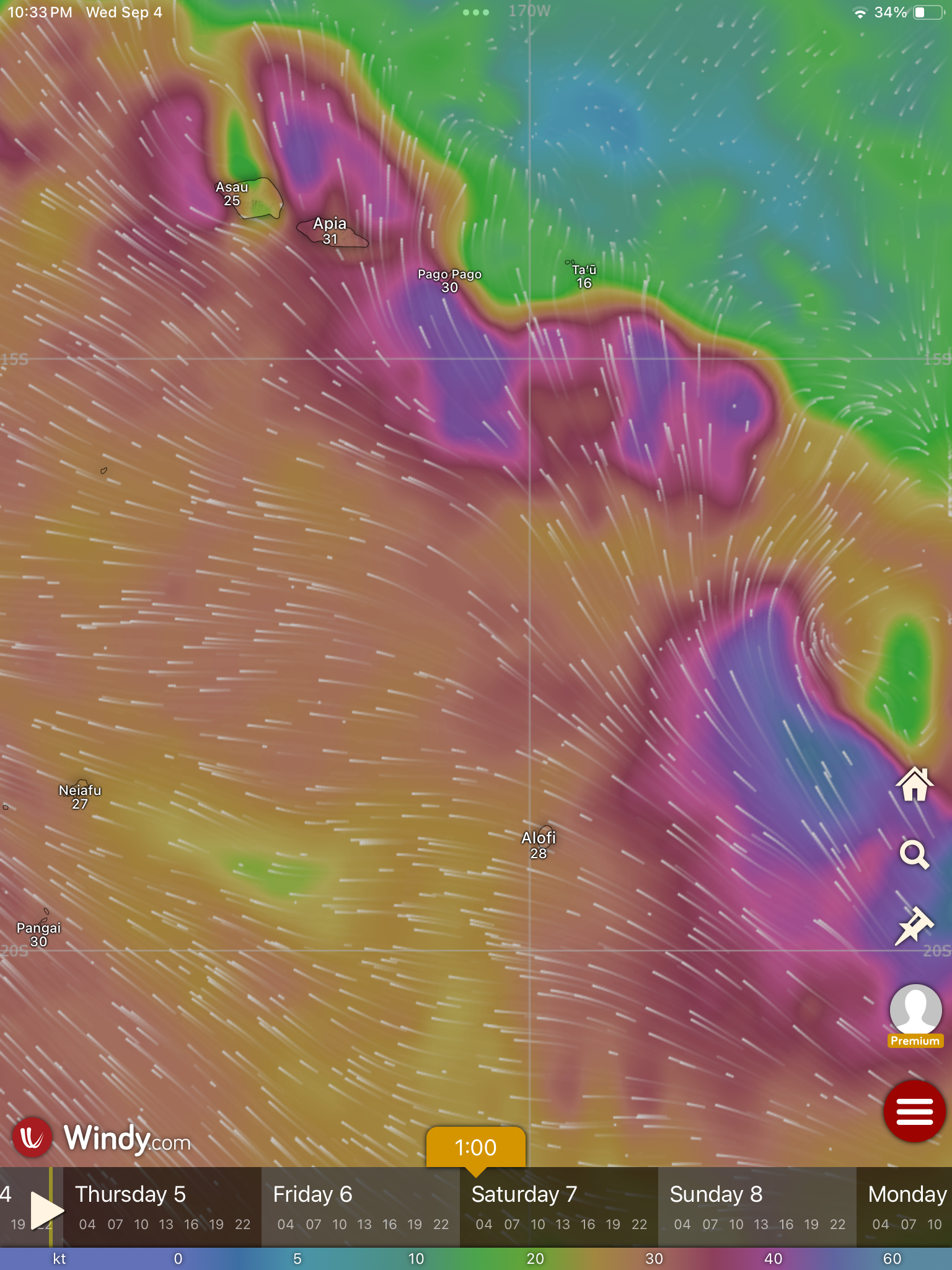

However, weather was not being very cooperative with our best laid plans to leave within three days time. We had been watching the weather forecast models already for quite some time. There was currently a massive zone of absolutely zero wind between us and Tonga, which was where we were trying to get to, and it didn’t look like there was any chance of it filling in before our deadline to be out of the country. By massive zone, I mean over a thousand miles – a distance that would take us over a week to motor through and would consume nearly the entire capacity of our two hundred gallon diesel tank…almost twice the amount we had used since departing Mexico four months ago.

There were other boats that had already decided they were headed for Bora-Bora or Maupiti. They planned on just trying to hide out until the winds finally picked up.

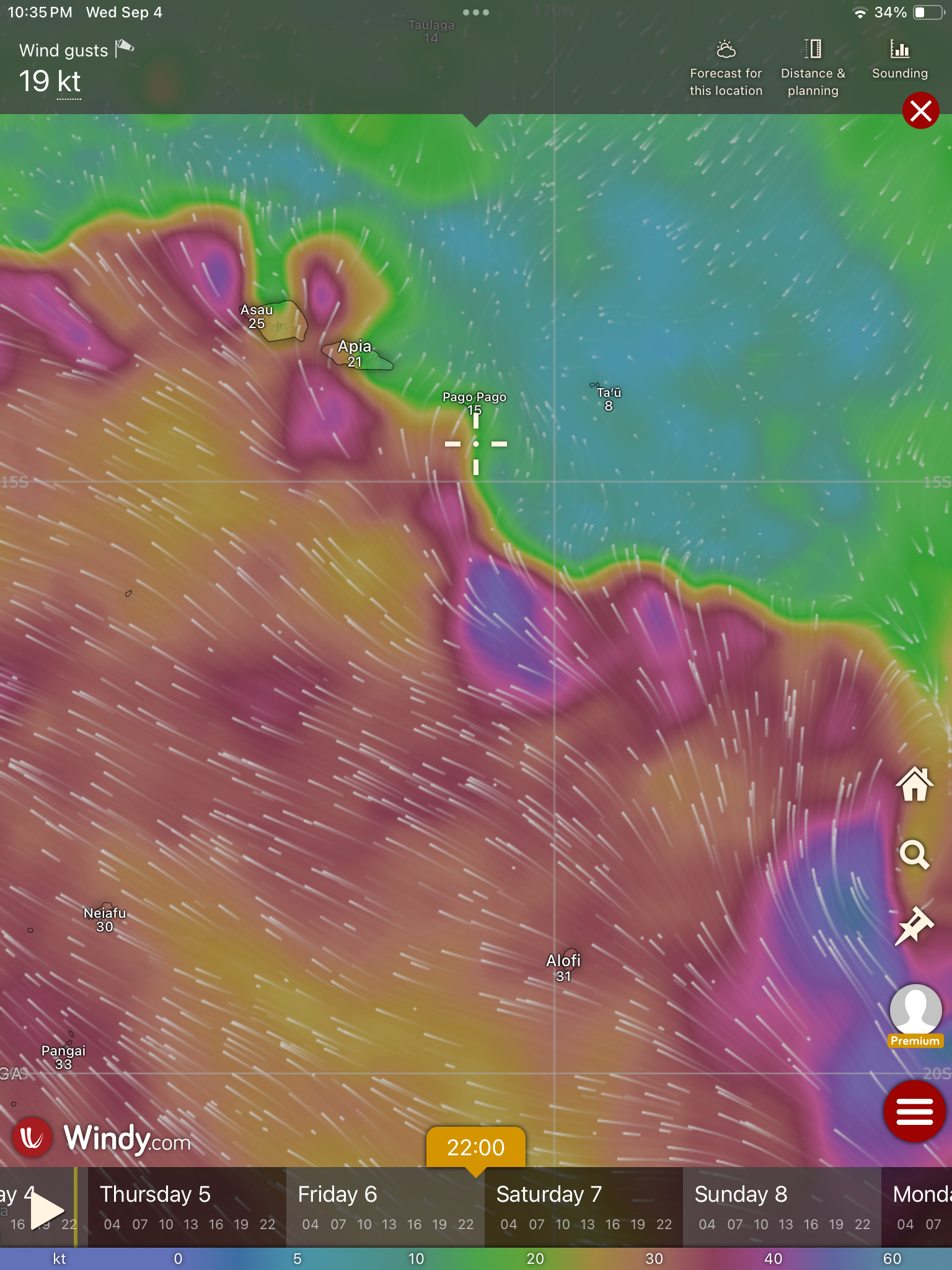

An additional problem was the longer term projected forecast. By the evening of September 1, stronger winds that were currently arcing to the south, just under the present dead zone that represented our needed trajectory, were expected to not just fill in to the north, but actually kick up to pretty damn obnoxious levels. These could be winds reaching the thirties with seas building up to ten feet or higher…something we were not prepared to sail through.

If we didn’t leave soon, we wouldn’t for quite some time…

We hatched a plan that seemed far more prudent than what amounted to the general consensus and groupthink among many of the other sailboats. It would mean we would be completely on our own, without the comfort or backup of nearby buddy boats, but we had never favored that strategy anyway.

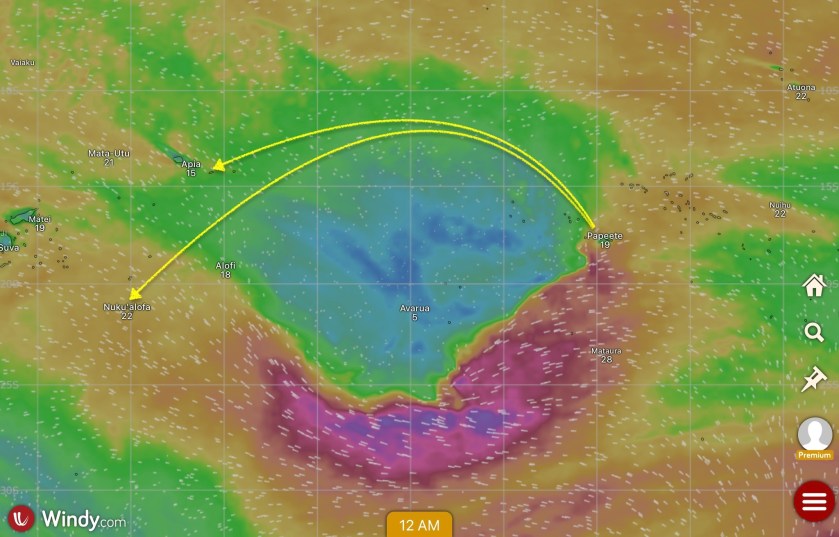

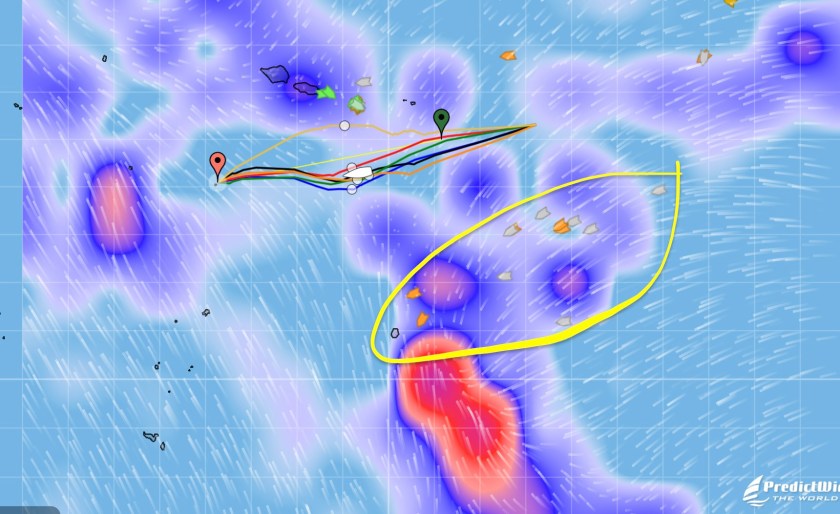

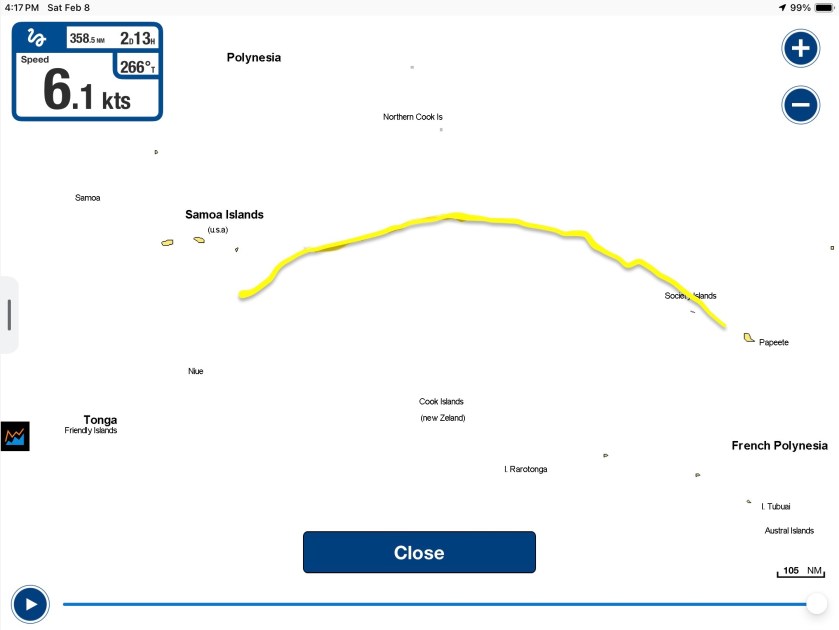

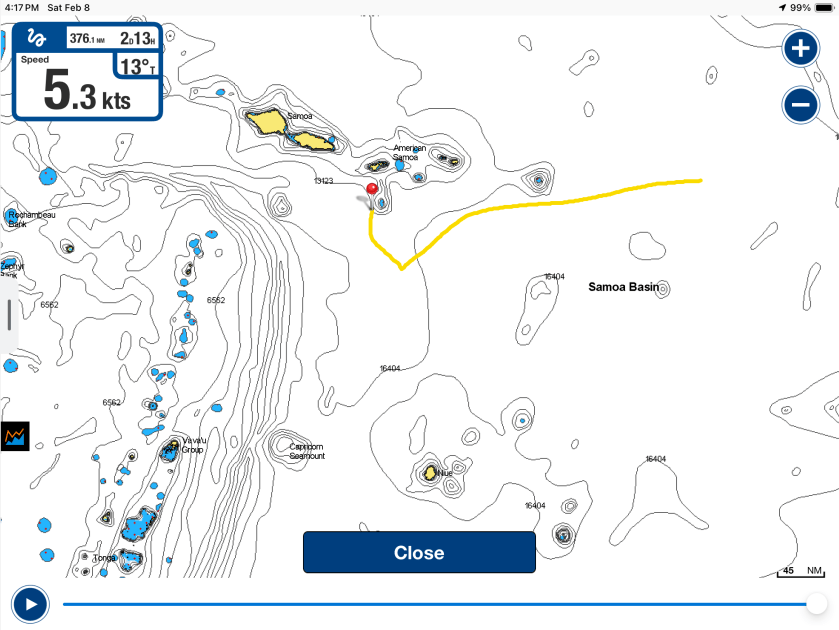

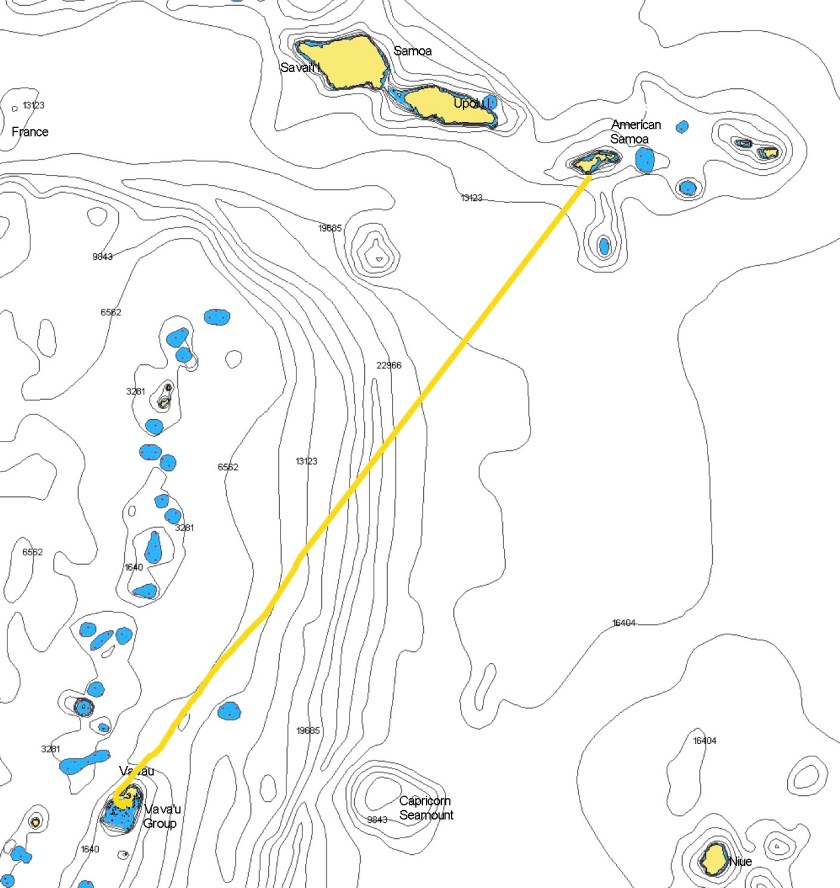

Instead of attempting a straight shot involving potentially motoring for the better part of a week, or hiding in Bora-Bora or Maupiti hoping we wouldn’t get caught, we decided to head north. We calculated a broad arc in that direction, skirting along the edge of the dead zone would add potentially three hundred extra miles (maybe three days) to the projected thirteen hundred nautical mile, eleven day passage to Tonga, but should allow us the ability to sail instead of motor.

If the winds filled back in, we could cut back on a straighter course, possibly even stopping at Alofi on the tiny remote island of Niue (about two hundred miles short of Tonga) – an idea that intrigued us greatly. If things went completely to shit with that plan, American Samoa would be the bailout option at around eleven hundred miles, or nine days.

We set out on our own path, and for two days we enjoyed brilliant sailing conditions. Thirteen to eighteen knots in comfortable seas on a broad reach. Then the winds dropped to less than ten knots and we found ourselves motoring for half of the next forty-eight hours.

Once we got underway, the forecast models began to revise. The upside looked promising – though still covering a vast area of ocean, the zero wind area looked like it might shrink somewhat, potentially permitting us to avoid having to push as high northward as we originally anticipated. However, the downside looked slightly ominous – winds on the south side of the dead zone were probably going to be strengthening much more than originally forecasted. Niue would more than likely be too rough to stop at.

By our fifth day underway the winds had consistently returned. Nothing less than low teens and nothing more than low twenties. The skies were clear and we were smiling. It seemed our strategy had been a solid choice and we were making excellent progress.

We were growing a bit concerned with shifts in the forecast models that were still over five days away – far enough ahead to likely change again but close enough that we would still be underway.

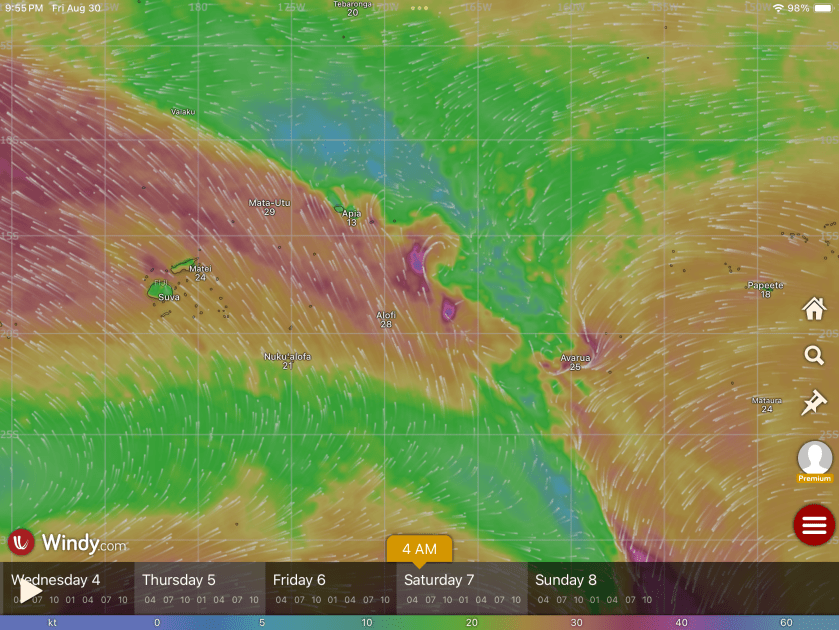

The projections were now looking at a major disturbance beginning to materialize stretching from Tonga all the way up to Samoa and nearly two hundred miles east of Niue.

We had all but removed Niue from the potential list of potential targets; it looked like it was going to be a mess. Instead, the tiny island of Suwarrow (technically part of the Cook Islands), east and slightly north of American Samoa, had now become our bailout option in case the original fallback option of American Samoa became untenable. It looked like the shit could hit the fan even as far north as Samoa. This was one of those times when our ability to connect to Starlink and get weather updates while more than five hundred miles from the nearest land in the middle of the Pacific Ocean was worth every penny we had to fork out to a prick like Elon Musk.

By sunset on day six, you wouldn’t have guessed what winds were in store for the near future. They had dropped back down to below ten knots and we would see as low as five. We had managed to sail for one hundred ten of the past hundred fifty hours underway – not perfect but our “northern arc strategy” had largely been paying off. Still, it became excruciating having to run the engine for a number of eight to fifteen hour stretches.

On day seven we scrapped our improvised tentative stop at Surarrow. We had made good on about seven hundred thirty miles and actually came within less than thirty miles of the island. The forecast was still ambiguous as to whether things were really going to get nasty and we had American Samoa 450nm ahead of us that we would pass in about three days. If we were able to press on to Tonga we had closer to 700nm ahead of us, meaning we had just passed the halfway point.

Meanwhile, we had been hearing reports from the armada of twelve or so sailboats three to four hundred miles to the south of us. This was the group that had hidden out in Bora Bora or Maupiti and made a run for Niue just ahead of the front that we had tried to get well north of. They were now being pummeled by brutal winds and high seas, still trying to make it to Niue before conditions deteriorated enough to make entering the pass into the atoll impossible, forcing them to continue all the way to Tonga. From the AIS positions that we were seeing on our PredictWind weather updates, it looked to us like very few of those boats would make that window.

That afternoon we celebrated having surpassed 22,000 nautical miles travelled aboard Exit. It was a welcome momentary distraction from worrying about weather forecasts. We were glad to have taken our own path and followed our own instincts.

Two days later we had to laugh. We were now making around one hundred fifty miles a day, averaging almost six and a half knots of speed – which for us is screaming along. Entering day nine of our passage, we had traveled more than one thousand nautical miles and were still yet to lock in a destination. Currently we were splitting the difference between Tonga and American Samoa, pointing right between the two of them. It was messy as hell all around us with seven to ten foot seas and winds averaging in the low twenties, but we were hauling ass on a broad reach, sailing in waters that would reach over 16,000 feet deep as we prepared to pass over the the Samoa Basin. Having to make almost no sail adjustments whatsoever, we were content to keep going.

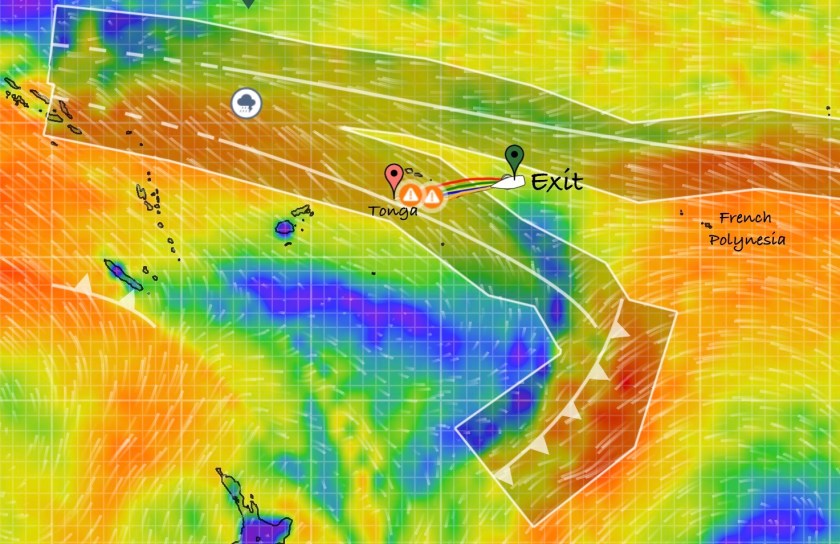

The following morning we realized we had travelled five thousand six hundred nautical miles since departing Mexico. Today we would pass twelve hundred miles on this passage and had made a definitive turn southward from American Samoa. Our sights were set on Tonga. The shifting weather forecasts were so schizophrenic they were making us dizzy, but we thought we had a narrow passage that would avoid the worst looking stuff that was threatening forty or so knot gusts. We had about 350nm to reach central Tonga; north Tonga was about one hundred miles closer.

Over the course of the next twelve to eighteen hours things would change drastically.

By midnight we were already more than one hundred nautical miles south of American Samoa. We had started experiencing squalls with wind gusts punching up to thirty knots.

That wasn’t pleasant at all.

But what began to grow scary very quickly was the rapidly changing forecast models which indicated a much worse deterioration of conditions and strengthening winds than we had previously seen indicated at all, up to this point.

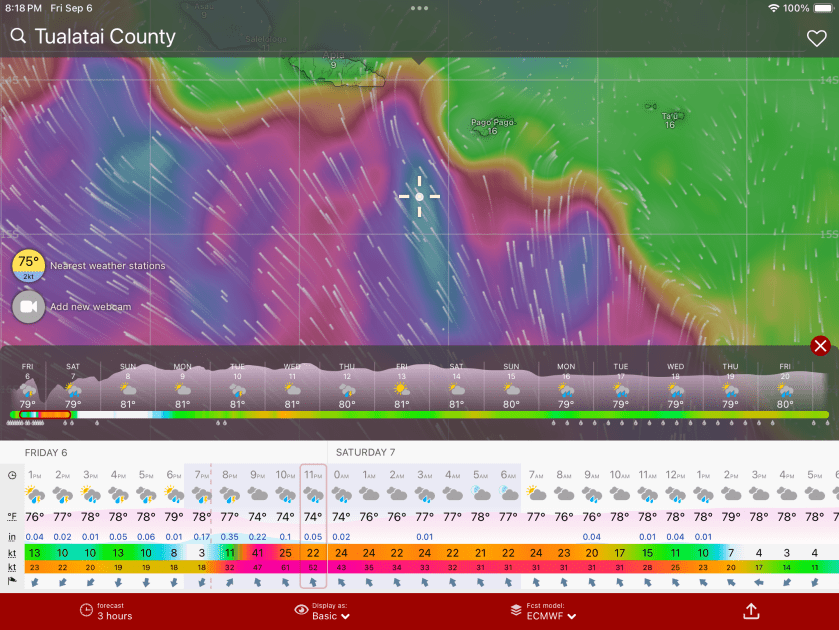

When we briefly turned on Starlink at midnight we were shocked by the newest updated forecasts we had just downloaded.

The edge of the front had hardened up substantially and it no longer looked like a brief time period with gusts of thirty and some areas possibly reaching a bit higher. We were now seeing projections of much larger area that would be affected by longer lasting and much more substantial winds.

Now, in less than twenty-four hours, directly in the path of our current trajectory, we could expect to experience sustained winds into the forties with gusts ranging from the forties all the way up as high as the sixties for half the night! The models indicated fourteen foot seas could be anticipated!

Shit.

We immediately decided to abort, do an about face, and make a run for American Samoa. At about one hundred fifteen nautical miles away, we weren’t confident, even if we motor-sailed the entire way, that we would arrive in the harbor of Pago Pago before 9pm, when the shit was projected to hit the fan, much less getting there before dark.

Still, we had no choice.

Between midnight and dawn we tried to make as much progress towards American Samoa as we could; however we had to run with the wind and waves as squalls passed. Outside of the squalls, winds between eleven and fifteen knots from behind us limited our speed but we had to maintain pretty conservative sail configurations considering the number of squalls that were materializing around us and their intensity. By sunrise, we were motor-sailing to try to eke out every knot of speed we could squeeze.

At noon, we were less than fifty miles from Pago Pago and at 4:20pm the log noted we were twenty three nautical miles from the harbor. This meant we would arrive after eight…no chance of making it in before dark.

At least conditions had settled drastically as we approached the island. We knew this was deceiving; but it would certainly be in our favor to help us get into the harbor and try and find a safe place before all hell potentially broke loose.

Our no entering an unfamiliar anchorage after dark rule was sound practice but in this case we were going to have to say fuck it. There was no way we were going to risk sitting out for the entire night in potential fourteen foot seas with wind gusts possibly reaching fifty or sixty knots, and once things became untenable it would be even worse trying to get in.

We decided, especially if the current conditions maintained during our arrival, we could creep in slowly, hoping the lights of Pago Pago might help us to decipher things, and we would be taking the lesser risk. The maelstrom that was chasing us down from behind was now forecasted to hit American Samoa at 10:00pm. We estimated this would give us at least an hour to get our anchor set but certainly not more than two.

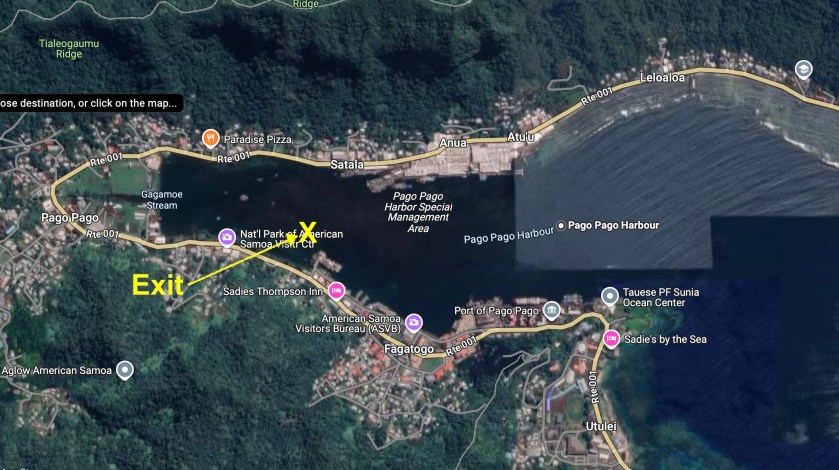

Pago Pago’s harbor opened out to the south; unfortunately, the direction the winds would be coming from. However, we knew that the anchorage itself was in the very back corner of the bay, which was tucked around a ninety degree corner to the west. Of course, it was impossible to know what we would find once inside the harbor and exactly where we would end up anchored, nor how the winds would funnel through.

Not ideal, but we felt it was undoubtedly our best option.

Though absolutely nerve-wracking and incredibly stressful, our entrance into Pago Pago Harbor was as smooth and uneventful as we could have hoped for. Lights from ashore both illuminated the bay to a certain degree but also made it very difficult to discern what it was we were seeing in front of us. A number of huge barges secured to massive industrial moorings with multiple derelict boats rafted up to them were nearly all but invisible to us, even with me at the bow with a handheld spotlight.

Regardless, after motoring amongst the barges and the handful of other sailboats at anchor, we managed to locate a spot that seemed to provide adequate room around us. We dropped anchor and got the snubber set just as the clock shown 10:00pm.

After ten and a half days at sea and one thousand three hundred sixty six miles, we had reached our detour stop of American Samoa.

That night, when the winds began to pick up around midnight, the land mass we were now surrounded by did indeed offer us immense amounts of protection from the wind. The orientation of the harbor also ended up sheltering us from any waves and, indeed, most of the swell.

We had made the right choice.

In hindsight, we were a bit irritated at ourselves for not having made the call earlier to divert to American Samoa. It would have been much easier. But, hey…in the end, boom. It had only taken us two hundred twenty five hours and over twelve hundred nautical miles, but we had finally made a decision.

A couple of days later, we would learn from a sailboat that had to be towed in by the Pago Pago police patrol boat, just how bad things were on the open ocean that night. They had lost all engine power and were forced to sail through everything, too far away to make it into the harbor until after things had settled down. They experienced fifteen foot waves and upwards of fifty knot winds. The two short-term crew members said they actually began to fear for their lives and now were hoping the captain couldn’t sort out the engine issues in Pago Pago so they would have an excuse to find another way off the island.

We had definitely made the right choice, even if a bit late.

It turned out our biggest mistake was the precise location we chose to drop anchor the night we had arrived at Pago Pago. Not that we had a lot of options in the dark, nor specific local knowledge to guide us (aside from the general understanding that the bottom of the bay was potentially littered with a lot of shit and debris). As we started to raise anchor so we could move to the government dock to clear in, we quickly found the chain hung up on something. There was no indication on the charts, but there was no doubt whatsoever we were seriously wrapped around something. We tried everything we could think of – moving forward and backwards, letting out chain and bringing it in, different angles, over and over again. Nothing. We were getting close to reaching the frustration threshold of having to don scuba gear to jump in the near zero visibility water and try to sort things out fifty feet below. Finally, well after an hour of frustration and desperation, we somehow managed to free ourselves. Whew.

We were told a short time later that the massive barge that had been on our port side, which at the time we set anchor appeared to be plenty of distance away from us, once had a seventy foot sailboat rafted up on its starboard side just prior the last cyclone that had hit American Samoa. By the time that cyclone had passed, the sailboat was gone. It had broken free of the barge and immediately sank. Currently, it lay on its side in over fifty feet of water with its over hundred foot mast pointing straight towards where we were anchored.

We had most certainly gotten tangled up on its mast and or rigging. Major pain in the ass, no doubt. Close to a disaster.

But, now that we were here and cleared in and anchored in a slightly different location, we figured we might as well spend a bit of time enjoying things.

A number of times we found ourselves the recipients of the extra large hospitality and friendly nature of the extra large Samoan people. A few times, working our WSU Cougar Alumni status into conversations seemed to gain us even more traction – the historical list of Samoan Cougar football players is extensive, indeed. Confessing that I had watched the “Throwin’ Samoan” Jack Thompson quarterback for WSU all the way back in the 70’s when I was only ten years old got me instant cred with a guy who said he’d actually played high school football with NFL powerhouse linebacker Frankie Luvu. He shouted out “Go Cougs!” as he walked away, after offering to do anything he could to help us out while we were visiting.

One of the bonuses of a new country is being introduced to its local beer. Of course, with the local beer Vailima, the Samoans boast not only extra big cans but also extra big alcohol content. Woohoo!

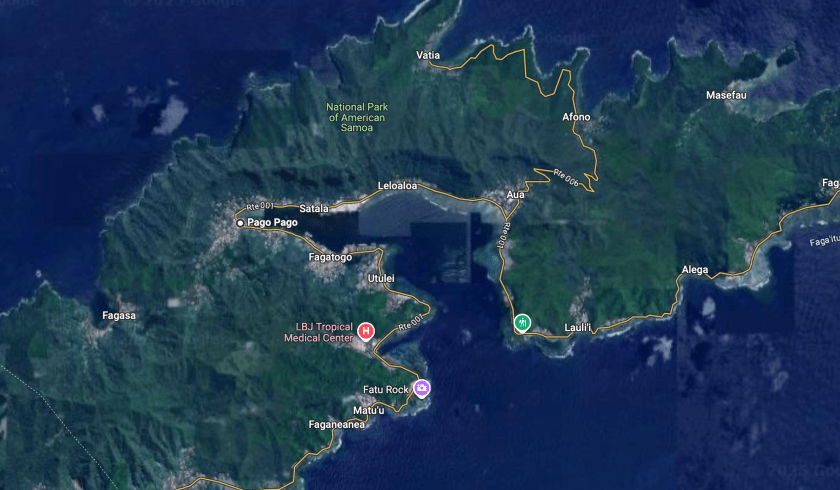

We spent ten days in American Samoa. If you could ignore the imposing presence and especially imposing smell of the massive Starkist tuna cannery right along the nearby shoreline (a nearly impossible task when it was directly upwind), the scenery was rather breathtaking.

There was no way we weren’t taking advantage of the incredible provisioning options which Pago Pago offered. An actual Costco in the middle of the Pacific Ocean? Are you shitting me? But, of course…the American contribution to American Samoa.

We also opted for yet another car rental. Damn…between Mexico, Moorea, and Pago Pago, aside from our visits back to Washington state, we had driven more in 2024 than we had for the previous ten years combined.

In the end, we had thoroughly enjoyed our unexpected detour to American Samoa. But after ten days, ironically enough this was almost the exact same amount of time it took us to get here, it was time to pick up anchor and complete our passage to Tonga.

Prior to departing, we had been forewarned by a salty Kiwi who had spent years delivering charter boats between Tonga and New Zealand that the 300nm two to three day passage from American Samoa to Tonga could be bouncy and unpredictable.

Great.

After our meandering, indecisive, and dramatic last journey, that was just exactly what we didn’t need, thank you very much.

Nonetheless, we remained optimistic. As we picked up anchor and motored toward the opening of Pago Pago Harbor, a bright blue sky filled with puffy, white clouds floating above an equally bright blue and perfectly calm sea state seemed to reflect that optimism.

Likewise, Kris’ calm state and smile also seemed to reflect that optimism.

As we cleared past the outer the edge of the harbor, the water’s depth under Exit plummeted almost instantly to 10,000 feet. Within a mere additional two miles, that depth had doubled to 20,000 feet.

In fact, during the next two days 20,000 feet would be the average ocean depth under us as we crossed the Tonga Trench. Though we didn’t actually pass over Horizon Deep, which at 35,702 feet is the deepest point in the Southern Hemisphere (and second deepest on our planet after Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench), the incredible indigo blue water surrounding Exit hinted at what seemed like infinity stretching out underneath us.

The first night sucked. Big winds that approached thirty knots; big waves eight to ten feet tall; big rain – water everywhere inside and outside the cockpit. More than once, we began to start questioning our choices. Exit’s log entry reads simply: What a fucking mess…not found anywhere in the brochure.

Just after midnight, a brief reprieve in the rain treated me to an amazing phenomenon I had never before seen. Against the overcast blackness of the night, a light blue haze began to materialize into a definitive arc that rose from the dark seas, bending upward and then returning to the currently invisible horizon line. As is often the case with nighttime lights underway, I spent a few confused seconds processing what I was looking at before smiling and saying out loud to myself – I was the only person in the cockpit during my turn at the night watch – “Holy shit, a midnight rainbow.” I later learned of the term nightbow.

Day two was about five knots calmer in wind. Sporty, to say the least. But we were hauling ass, averaging a speed of between six and seven knots.

The second night was what sailing is all about. No rain with no winds over twenty knots. We were zooming steadily along at between five and seven knots.

By 10:00am, the morning after our second night, we could see Tonga clearly on the horizon…land ho!

Ninety minutes later, it seemed fitting as we passed over a canyon 23,000 feet deep to make a toast to our own achievement of having just surpassed 23,000 nautical miles traveled aboard S/V Exit in just over seven years. That included 6121nm since departing Mexico less than five months ago. Cheers!

We had been sailing non-stop without needing the engine for propulsion since two hours into the passage. Over three hundred nautical miles without having to adjust our heading by more than ten degrees. Nearly a straight line. You can’t ask for more. Well…you can, but now you’re being greedy dick.

By that afternoon we were inside the protection of the Vava’u island group. A mother whale and its baby had even briefly greeted us as we passed by.

With an hour to spare before sunset, we found ourselves toasting each other for the second time in one day. This time, anchor beers just off Mala Island.

Amazingly, we had averaged nearly one hundred sixty nautical miles for two consecutive twenty four hour periods. We had only surpassed one hundred sixty miles in twenty four hours once, that was four and a half years ago when Covid 19 was chasing us like a Hellhound on our trail, all the way from Grand Cayman to Bocas del Toro, Panama, just before the world shut down.

We had just sailed three hundred fifty seven nautical miles in under fifty six hours. That too, was a record for us.

We had made it to the Kingdom of Tonga.