June 14 – August 5, 2024

Raroia, Fakarava, and Tahanea – The Tuamotus, French Polynesia

We had good light and nearly flat seas.

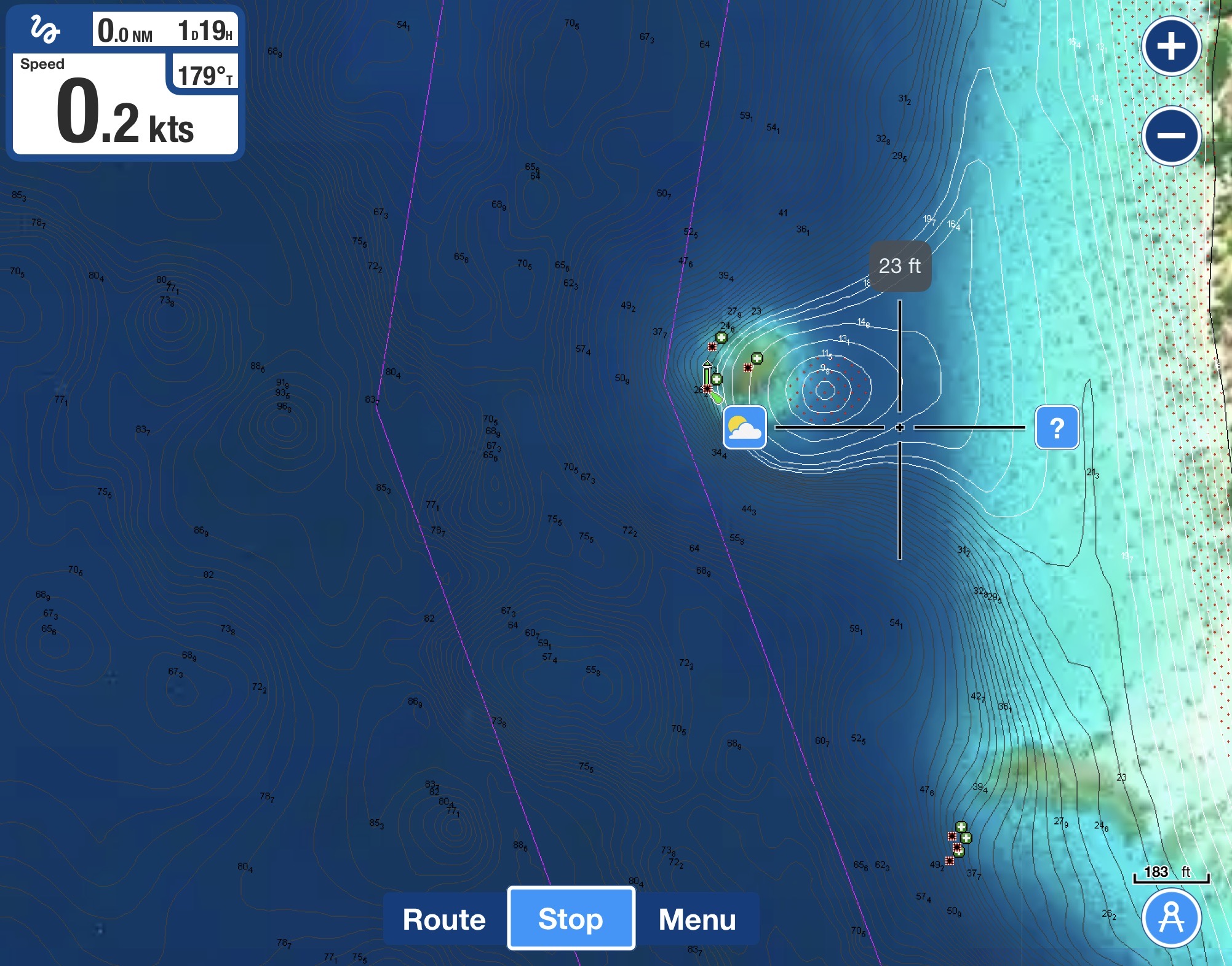

The pass into Raroia ranges from fifty to ten feet deep so we had plenty of depth to work with. And the pass is, by no means, narrow. At about a thousand feet wide, we had plenty of space to maneuver. However, with the oval shaped inner lagoon twenty miles long and about five miles across, the volume of water passing in and out of the atoll during tidal cycles could be huge. And with very few places for this water exchange to occur, this meant that currents inside the passes could be staggering.

At some atolls with narrow passes, combinations of strong currents and contrary winds could turn flat seas into six foot standing waves and create currents strong enough to prevent a sailboat engine from even being able to make forward progress.

The fair sea conditions we found ourselves in approaching Raroia bode well for our arrival. The wide pass helped to alleviate the nervousness of our first atoll pass entry. Even so, we found quickly how the conditions inside the pass could be quite different from those on either side.

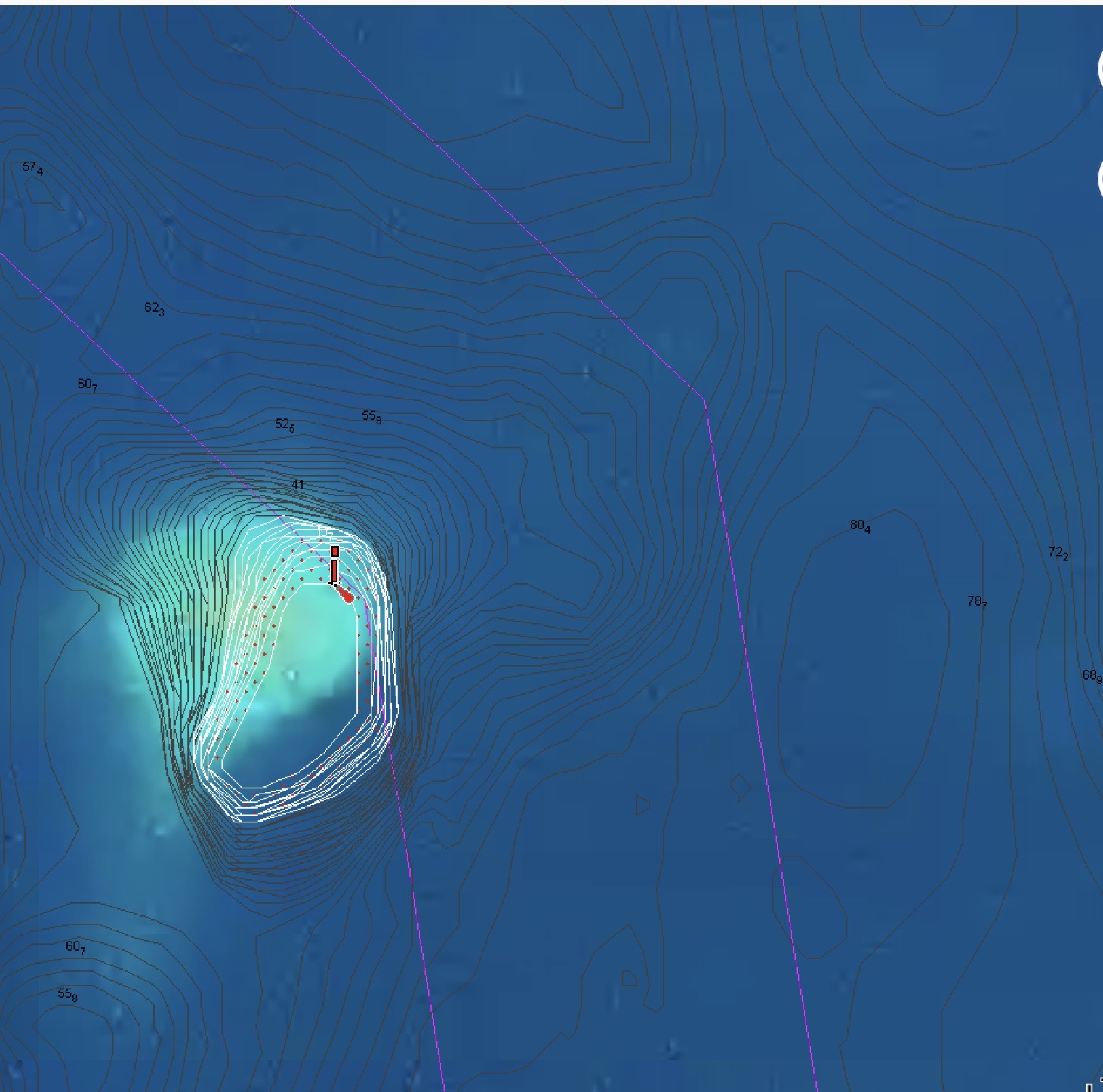

Once through the pass, the lagoon immediately settled back to a serene calm. We decided to thread our way through the six mile stretch of coral shoals and bommies to the other side of the atoll to anchor instead of anchoring just off the town which had even more obstacles to avoid and reports of poor holding.

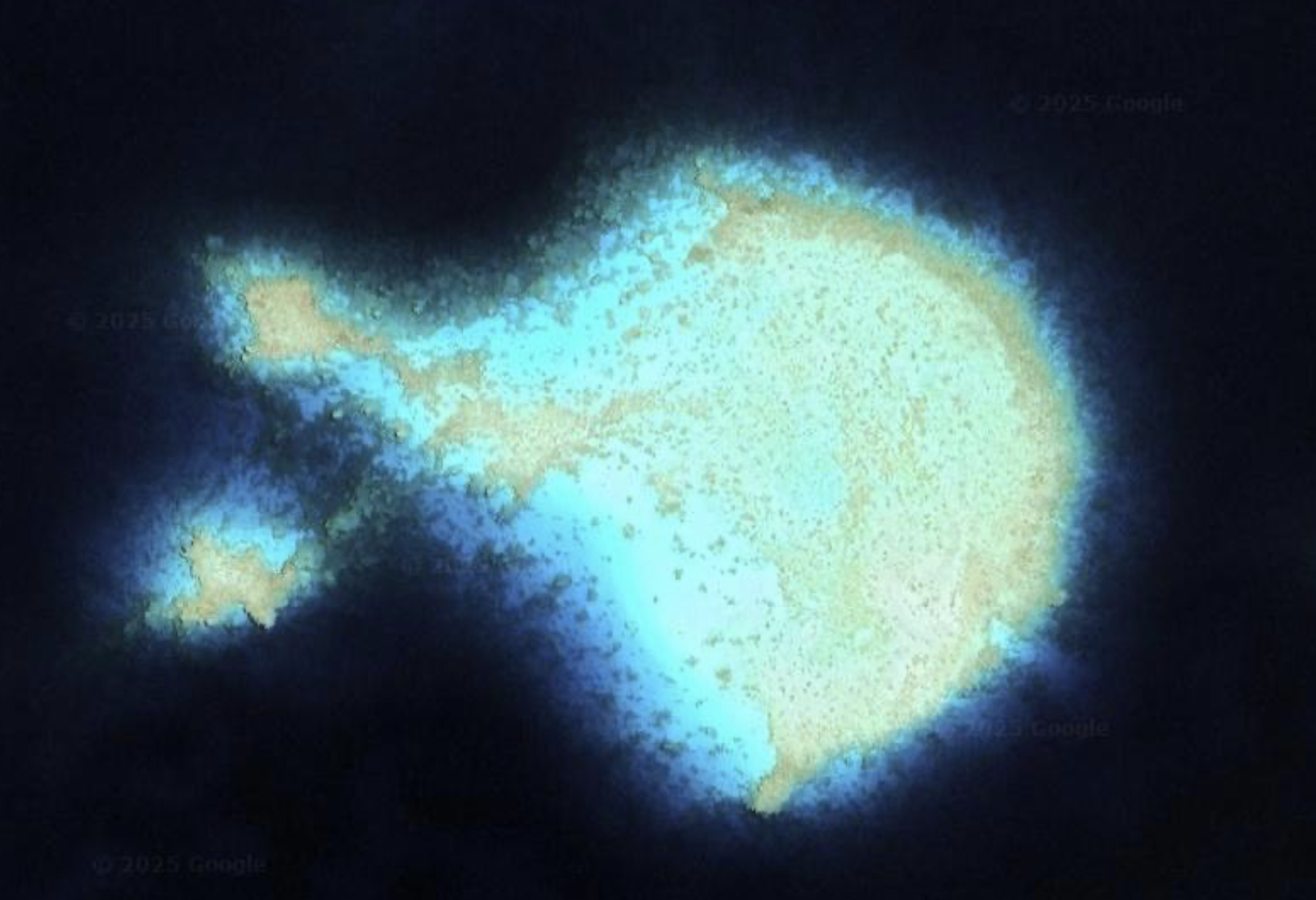

On Google Maps, it looked more like a satellite photo of clusters of galaxies and stars in outer space than a lagoon in the Pacific Ocean. A closer look revealed the field of lights to actually be shallows of rock, coral and sand that would best be avoided if one wanted to remain floating.

Cautiously, with someone occasionally at the bow acting as lookout, we picked our way through the navigational minefield until we reached the other side. With our chart plotter indicating exactly 420 miles had passed under our hull since departing Tahuata, we finally set anchor.

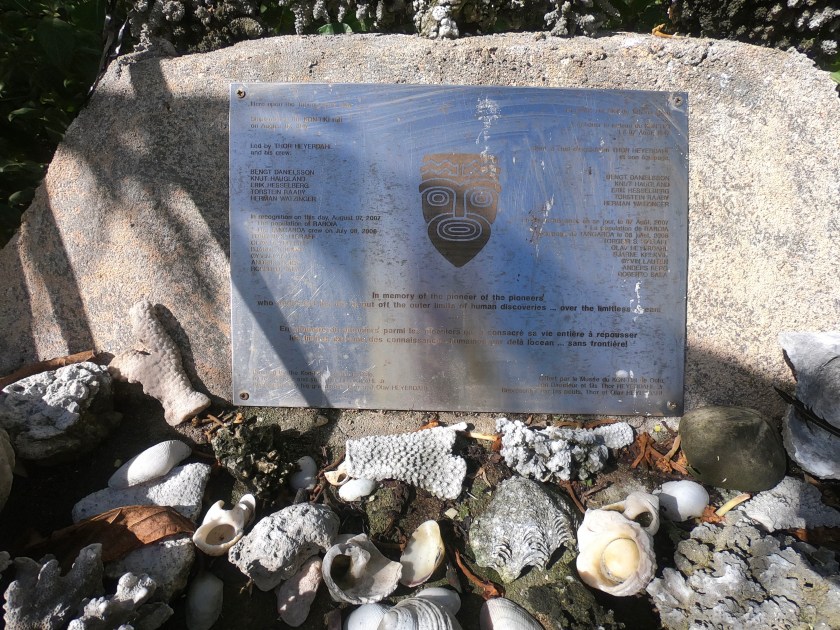

The anchorage we were at was named Kon Tiki. It wasn’t simply an obscure and distant reference to the famous Kon Tiki expedition.

The tiny island currently in front of Exit was the exact location Thor Heyerdahl and his crew came ashore in 1947 after their balsa wood raft Kon Tiki beached having just struck the outer reef of Raroia, 4340 miles from Peru where they had set off from 101 days earlier. At the time, Raroia was uninhabited; Heyerdahl’s party had to wait alone on the island for days until they were rescued by villagers from a nearby island.

Fortunately, we had arrived at the island from the other direction, having had the advantage of accurate electronic charts, engine power, and a more functional sailing vessel. Instead of lying exhausted in the sand, traumatized by having nearly been drowned and crushed on a reef, we were able to enjoy ice cold anchor-beers in our cockpit.

Even better, a short time later, one of the local inhabitants came up alongside us in his small boat and indicated that he had fresh fish prepared three different ways available for us to purchase that was extra from a gathering that was about to commence. Sweeeeeet!

The following day we ventured onto the tiny island for a look around.

Sure enough, there was the Kon Tiki plaque which had been placed to commemorate Heyerdahl’s epic expedition. Even if contemporary opinion questioned the scientific validity and racial underpinnings of the crew’s adventure as quite controversial, we could certainly appreciate their accomplishment, having just travelled nearly the same trajectory. We thought we were slow moving…fortunately we had fared better than the 1.5 knots they averaged during their voyage.

In one of the tide pools we stumbled across what appeared to be a hermit crab orgy…

Subsequent days were spent doing daily boat tasks and projects interspersed with moments of rest and relaxation which included snorkeling, dinghy excursions, swimming off the transom, and trips to the nearby motus.

A ground level view from the outer edge of the atoll looking back towards the lagoon and then out into the open ocean:

Kris was finally able to get her SUP back up on deck (it had been deflated and stored belowdecks for the crossing from Mexico) and go out for regular paddles again. During one of these SUP explorations she happened across a moment of pure magic…a manta ray! It had been years since our last manta sighting and to say she was absolutely fucking stoked would be a hardy understatement.

When we finally launched the drone, Space Exit gave us the best visual perspective we had seen so far. The view comparing Exit at anchor inside the atoll with its gin clear water and amazing colors, the untamed Pacific Ocean outside, and the slim strip of rugged tropical paradise separating the two was spectacular.

A brief glimpse of a lone blacktop reef shark patrolling the lagoon was a bonus…

We spent about three weeks at anchor in Raroia splitting our time between the Kon Tiki anchorage and one at the north end of the atoll.

One day while we were out and about in the dinghy we happened across a dozen or so people. Half of them were people from other sailboats anchored nearby; the other half were local inhabitants who had motored up in their small boat from the village ten miles to the south, just beyond the pass we had entered when we first arrived at Raroia, for a relaxing day at the beach. The locals had brought food, drinks, and a couple of ukuleles. We spent the afternoon eating, drinking and getting to know each other. I even had the opportunity to play along when one of the guys offered up his ukulele to me for a while.

During this time we also made arrangements to have the captain come back by a few days later to take six of us out for a dive in the pass. There was no dive shop. No guide. We had to bring all our own gear and sort out the logistics ourselves. He was a local who had lived on Raroia his whole life – an experienced fisherman and boatman.

Within minutes of entering the water, just as we started descending, we came face to face with one of the three species of sharks we have always said would make us nervous encountering…a ten to twelve foot tiger shark! The first we had ever seen. None of the other divers even saw it. It had turned away and disappeared beyond our range visibility before the two inexperienced divers had even dropped below the surface, but we had sure as hell seen it.

Moments later we found ourselves an area at the side of the pass that opened up like a bit of a horseshoe, alongside a wall, where quite strong currents were picking up. Dozens of grey reef sharks were circling around. The inexperienced divers had already drifted off with the current towards the inside of the lagoon before we had even reached the bottom but seemed not to be stressed or panicking so we continued on with the other two divers. We managed to locate a spot that we could maintain our position and remained there for quite some time, enjoying the large gathering of sharks.

Even with a random drop in the pass, the dive was incredible. We had seen our first tiger shark and came up at the end with huge smiles plastered across our faces.

However, everything comes at a price. Apparently King Neptune required a sacrificial offering in exchange for his generosity. We were on a small local boat build for transporting people and fishing, not diving, and we had to wrestle a bit to get ourselves and our gear back inside the boat. Once everyone was inside and we started to head out, we realized the one thing we were missing was our GoPro in its underwater housing that we had taken on the dive. The wrist lanyard had obviously slipped off at the surface as we struggled to get our equipment off and into the boat. Shit. It was gone.

Unfortunately, it would not be in the cards for us to acquire a replacement until we reached Tonga. Definitely, a real bummer…but we had seen a tiger shark!

During another one of our dinghy excursions to a beach I had a deja vu moment back to Pulau when Kris took an entertaining video of me attempting to open a coconut. Though I had not grown that much more adept at the task during the past fifteen years, I was eventually able to harvest the luscious coconut water while managing to keep all ten of my fingers intact. Fortunately for Kris, I refrained from the fake Australian accent this time around.

On our final day at anchor inside the atoll of Raroia we were treated to a full rainbow, even though the squall that had generated it had passed around us… the beauty of seeing a rainbow while avoiding getting wet.

The following day we departed Raroia bound for the atoll of Tahanea, some one hundred thirty nautical miles to the southwest. Makemo is the more popular destination for many sailboats, which may have helped prompt our decision.

Another overnight sail.

We expected winds in the upper teens. However, the twenty-four knot winds we were actually seeing as we picked up anchor, as well as a discrepancy in what we expected to be slack tide with no currents in the pass, led to one hell of a very messy start. As we bucked and rolled through the channel riding atop a four knot current (at least it wasn’t against us), we wondered if we had mis-calculated by a day or two.

We never saw less than nineteen knots of wind and it picked up as high as twenty-seven knots that evening with big eight foot waves. Sloppy…but doable. In the end, we endured what could be described as a quite sporty passage. But at least we were able to sail for twenty three of the twenty six hours. To our chagrin, our autopilot Jeeves once again decided to take part of the night off…at 1:30am of course. This was becoming a rather annoying habit.

We arrived at Tahanea just after noon and were digging anchor beers out of the freezer by early afternoon.

Over the course of a few days, we took the dinghy out for a reconnaissance and exploration in both passes.

The currents were too strong and conditions around the passes just not predictable and calm enough for us to consider an unassisted dive while leaving the dinghy unattended but snorkeling with the dinghy floating alongside us on a painter line seemed very doable.

Though disappointed to not be able to dive, we still maintained confidence that it would be worthwhile even snorkeling. We were soon very glad we had come to that conclusion. During our first snorkel in the left pass, we saw yet another tiger shark! At least ten feet long, it was just about the same size as the on we had seen on Raroia. However, without being underwater with our dive gear on (giving us more more of the appearance and feeling of being just another large predator), wearing only a mask, snorkel and fins at the surface left us feeling much more exposed and intimidated…more like prey rather than more like equal observers. Still, after a short time it gracefully glided off out of view. Holy shit… two atolls, two tiger sharks. We also saw big grey reef sharks and even bigger silver tip sharks swimming below us near the entrance of the pass over the next couple of snorkels. Amazing!

Again and again we find ourselves witnesses to breathtaking sunsets which simply cannot be adequately described nor captured by photos or video. Sometimes they manage to achieve even one degree beyond unimaginable.

Other days manage to be stunning for very different reasons. The holy shit moment of balancing an attempt to capture an incoming squall with the common sense of getting the boat buttoned down and prepared for the oncoming onslaught, even if short-lived can be quite entertaining. A common occurrence during these moments involves an exasperated Kris calling out, “What the fuck? Will you put that stupid camera away and come help me out?”

Making friends on the beach at the end of our stay at Tahanea:

After only one week in Tahanea, Exit set out for Fakarava. Not because we weren’t enjoying ourselves. Rather, because we had to keep reminding ourselves to not get stalled to the point we would end up regretting having run out of time before we had even arrived at the Society Islands.

The overnight seventy-two nautical mile passage from Tahanea to Fakarava was uneventful.

Despite having left late in the afternoon, by the following morning at 4:20am, we found ourselves only two miles offshore from the channel entrance at Fakarava, and ended up having to tack back and forth a safe distance away awaiting the rising sun.

We were glad we had not tried to enter the atoll in the dark. The channel didn’t offer a lot of room and was not a straight shot. Once through, we had to navigate around a marker that signaled a reef which split the channel in two and then thoroughly search through the anchorage area to find a clear enough spot to drop anchor. There were coral bommies everywhere.

Fortunately, we had grown comfortable with the technique of floating our anchor chain, and managed to get settled in a spot that wasn’t right next to other boats.

We had learned that Fakarava had a dive site in the south pass called The Wall of Sharks. In fact, Exit had passed directly over it on our way into the atoll. And while unaccompanied dives were something we had no problem with, we realized that diving the actual passes in the atolls created a whole different set of challenges, difficulties, and risks. This pass was not wide, had much more boat traffic, no ideal place to leave the dinghy, and potential for serious currents outside of slack tides. We concluded this was one of those times to simply anti up and pay to dive with an established dive shop.

We didn’t regret that decision.

The French divemaster Miti, her friend Helen, and another visiting diver with a massive camera were all incredibly friendly and very capable divers. The dive boat would drop us off out towards the outer entrance of the channel, and we would drift with the current back to the dive shop, located at the inside edge of the channel. Easy enough; plus we got to extend our dive at the end as long as our air would hold out.

The underwater landscape was breathtaking – stunning coral structures alongside the entire length of the pass we were diving. Hard coral – branching, brain, plate – soft coral, sponges, anemone. The amount of marine life was ridiculous. Hundreds of species of reef fish – more than we had seen anywhere in years – groupers, snappers, parrot fish, puffers, trumpetfish, needlefish, surgeonfish, triggerfish, trevally, anemone fish, damsels, stingrays, so many colorful anthias and other small coral dwellers, massive Napoleon Wrasse…and, of course, sharks.

So many sharks.

Often times dive sites are named for things that used to be present at one time in the long ago past. Or for something that, if you are really lucky and do enough dives at the same spot, you just might see. Or for nothing more than wishful thinking or marketing.

The Wall of Sharks was not one of these – no ifs, ands, or buts; it truly lived up to its name. Sharks and sharks and more sharks. True, we had seen bigger aggregations of sharks in a few places. Schools of hundreds, if not thousands, of hammerhead sharks – but only in the most remote corners of the Galápagos Islands. Congregating sharks in Palau and on the Great Barrier Reef of Australia- but only because they had been artificially attracted by food.

Here in Fakarava, it was different. These sharks were just hanging out in the pass. Naturally attracted to the area by consistent food and currents. And a lack of fishing boats. The visibility was amazing. The water was a comfortable 81℉ seventy feet underwater, more like 84℉ at the surface.

We could have dived the same area dozens of times without getting bored…or cold. A far cry from Mexico, where it seemed unbearable even just cleaning the bottom of the boat wearing two layers of wetsuits.

Unfortunately, our Go-Pro fiasco in Raroia, meant we had no way to document the experience. Still, sometimes diving without a camera allows you to really enjoy the experience even more – none of the distractions associated with bringing and using a camera underwater…relying on old school memory rather than digital storage. Great for the dive itself; not so much for the blog.

We enjoyed our first day’s diving with the dive shop so much, we did a few more after that. This included a fantastic dawn dive. The real challenge there was getting our dinghy to the dive shop in the pre-dawn darkness and currents. Once in the water, it was incredible – a night dive that transformed as the sun slowly rose during the course of the dive. The guy with the huge camera had a gigantic light attached which provided much better view of the area than our small torches. Dozens and dozens and dozens of grey reef and white tip sharks, still completely in their night hunting mode, patrolled around us continuously, circling in and out of the perimeter of our underwater lights. As light from the rising sun above us slowly penetrated the depths, we could make out more and more details of the surrounding area. Eventually, by the second half of the dive, the light illuminated the whole pass and the vast population of marine life transitioned back to its regular daytime activities. An unbelievable experience.

The divemaster’s familiarity with us after a couple of dives allowed Miti to grant us a lot of extra freedom to dive our own profiles. On one dive, there were a number of rather inexperienced divers in the group and she sent us on our way to essentially dive the whole time on our own. Phenomenal time!

Considering how little land makes up the actual land mass of an atoll, its actual size can be quite misleading, as was certainly the case with Fakarava.

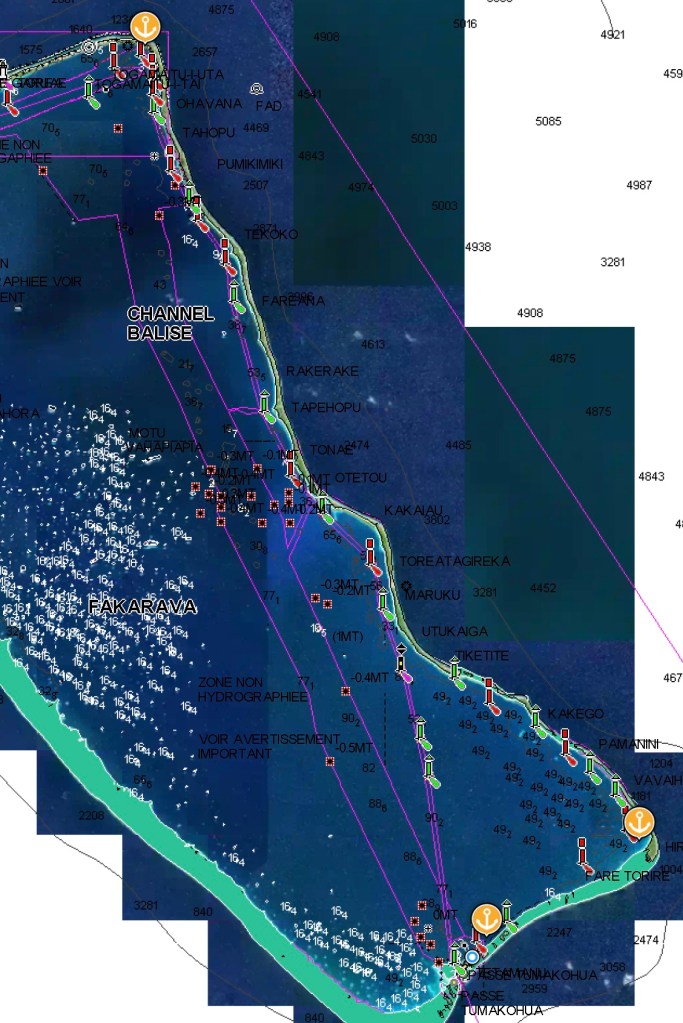

After diving, we decided to move from the southern pass area (known locally as Tumakohua) up to the northern side as the forecast indicated we could start seeing winds from the north. It took us most of the day to traverse the thirty five nautical miles from the south end to the north end, even motoring.

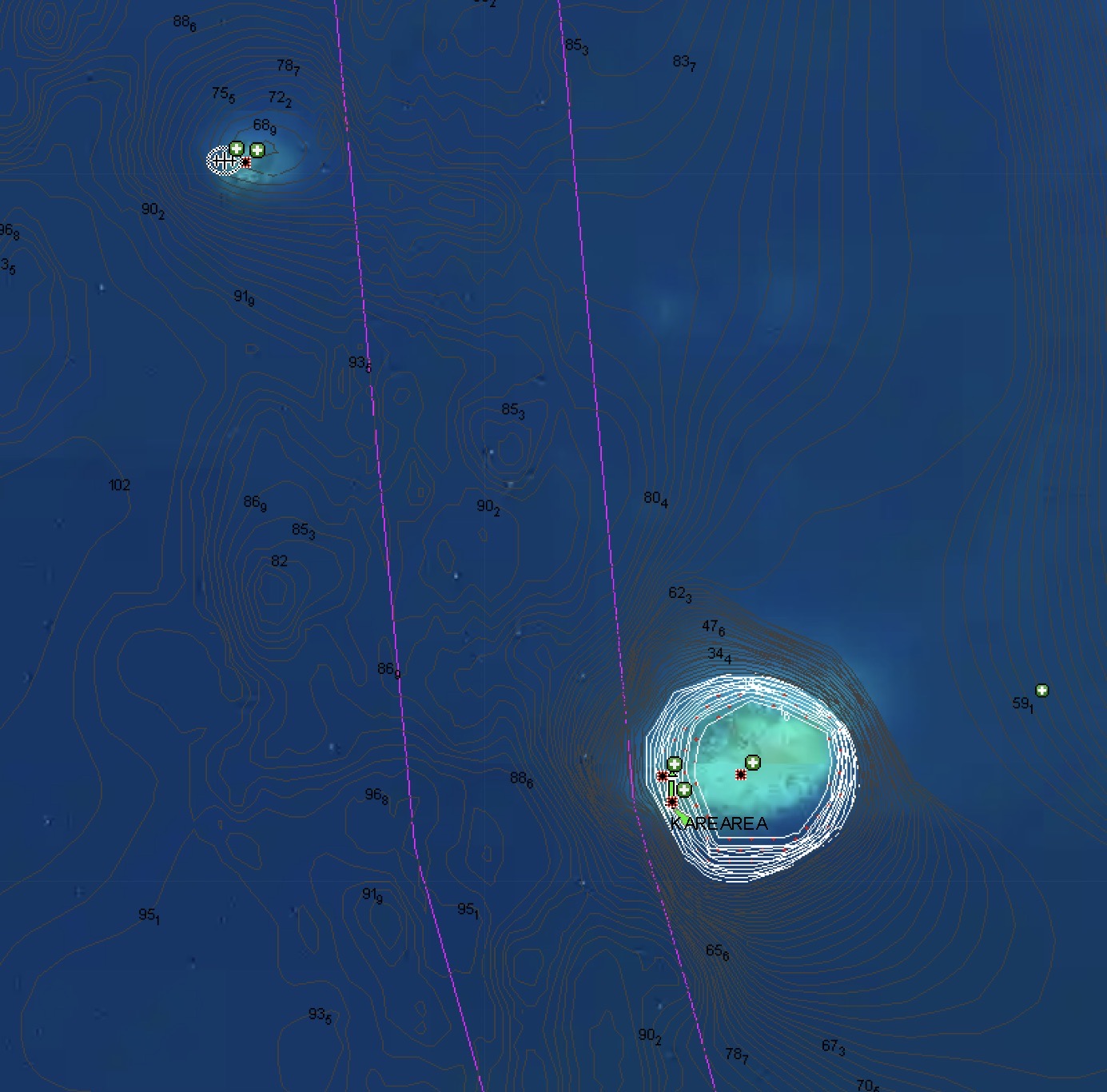

Our electronic Navionics charts provided a very specific and accurate channel complete with green and red markers to follow the entire distance. Furthermore, we are able to superimpose Google maps satellite photos over the top.

Still, despite the fact that some of the markers actually did exist and Google maps did do an excellent job of revealing the mine field of shoals, reefs, and rocks we needed to avoid (some visible jutting out of the water, but many submerged just under the surface), it was nonetheless mentally exhausting and stressful having to thread our way inside a mere six hundred foot wide track for the entire thirty five mile journey.

Furthermore, it was truly mind numbing to consider having to do that without the technology we had at our disposal.

It reminded us of navigating the ICW (Intracoastal Waterway) along the east coast of the U.S. years before. Though far longer, 3000 miles as opposed to 30 miles, at least a large number of the ICW hazards are nothing more than shoals and shallows. Much better to get stuck in the mud than sink after striking a seventy foot tall rock.

Fortunately, we made it to the north end without incident or drama.

Unfortunately, we didn’t have the opportunity to try diving the North Pass (which was reported to be not as stunning as the dives we had in the South Pass), but we did have a chance to visit the village of Rotoava while we were up in the northeast corner of the atoll.

After only a couple of days, including a ridiculously lumpy night with un-forecasted winds from the south, when the forecasts actually threatened south winds, we opted to head back south for better shelter and more diving.

Of course, gremlins and voodoo of the mechanical and electrical variety seem to come part and parcel with sailboat ownership. Even more so, the pendulum seems to swing even harder after exceptionally cool experiences like our dives in the pass.

Consequently, we shouldn’t have been surprised when, during the next big blow that passed through, we found ourselves having to sort out an impeller from our Perkins raw water system that appeared to have literally exploded while using the engine to charge our batteries at anchor during the relentless high winds, swell, and rain.

Mechanical headaches, stress, and unanswered troubleshooting questions that lead to periods of an out of commission engine in bad weather conditions while we are on a lee shore do not make for enjoyable situations…but such is life on a boat.

On the other hand, physics and the laws of Neptune dictate that the successful resolution of those obnoxious moments in time allow the pendulum to swing back in the other direction.

A more relaxing evening back at Tumakohua:

And a July sunset at Hirifa nearby in the southwest corner of Fakarava:

Of course, it all depended on what day you were talking about. Three days later the same spot at Hirifa presented quite a different scene.

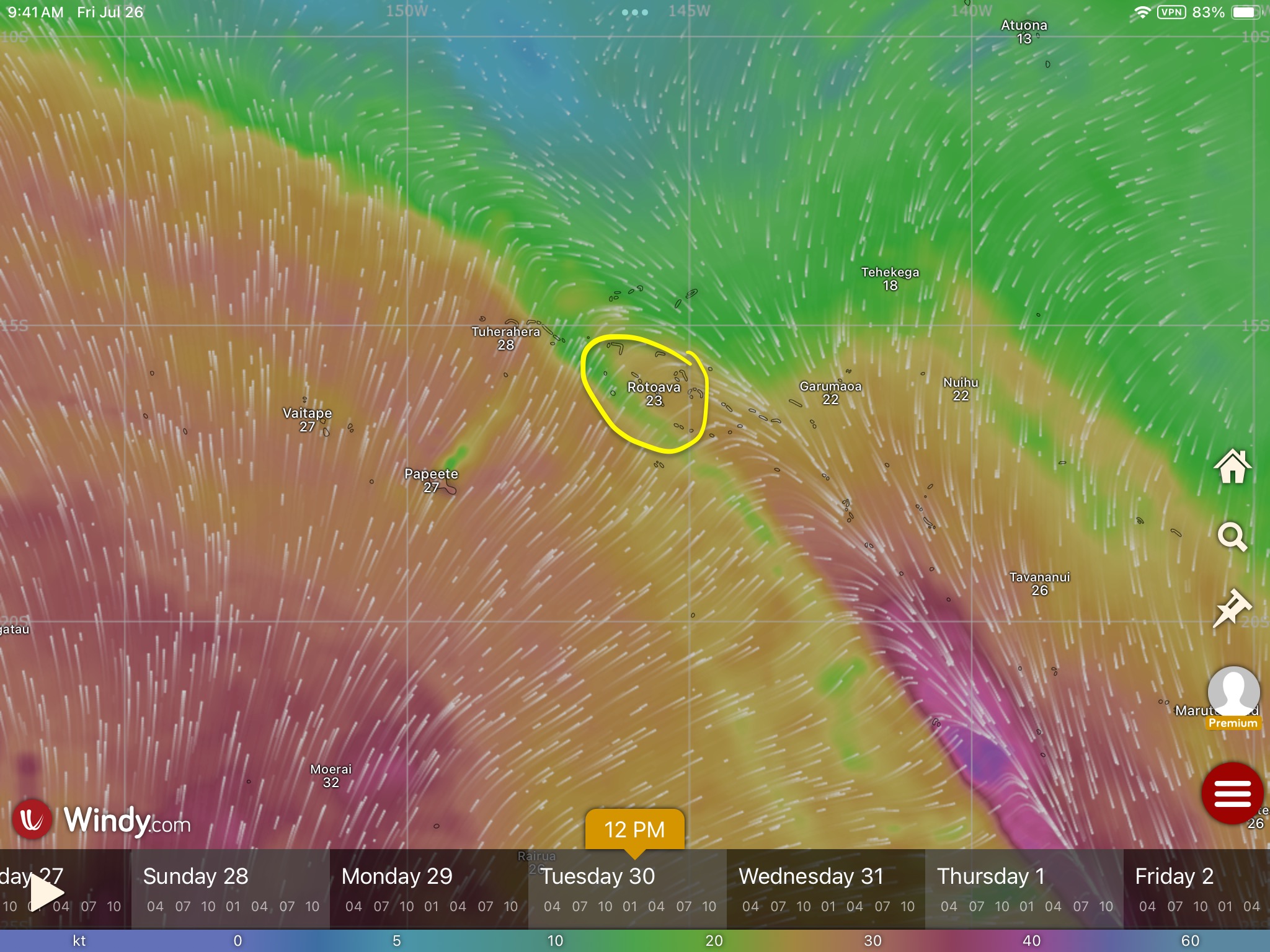

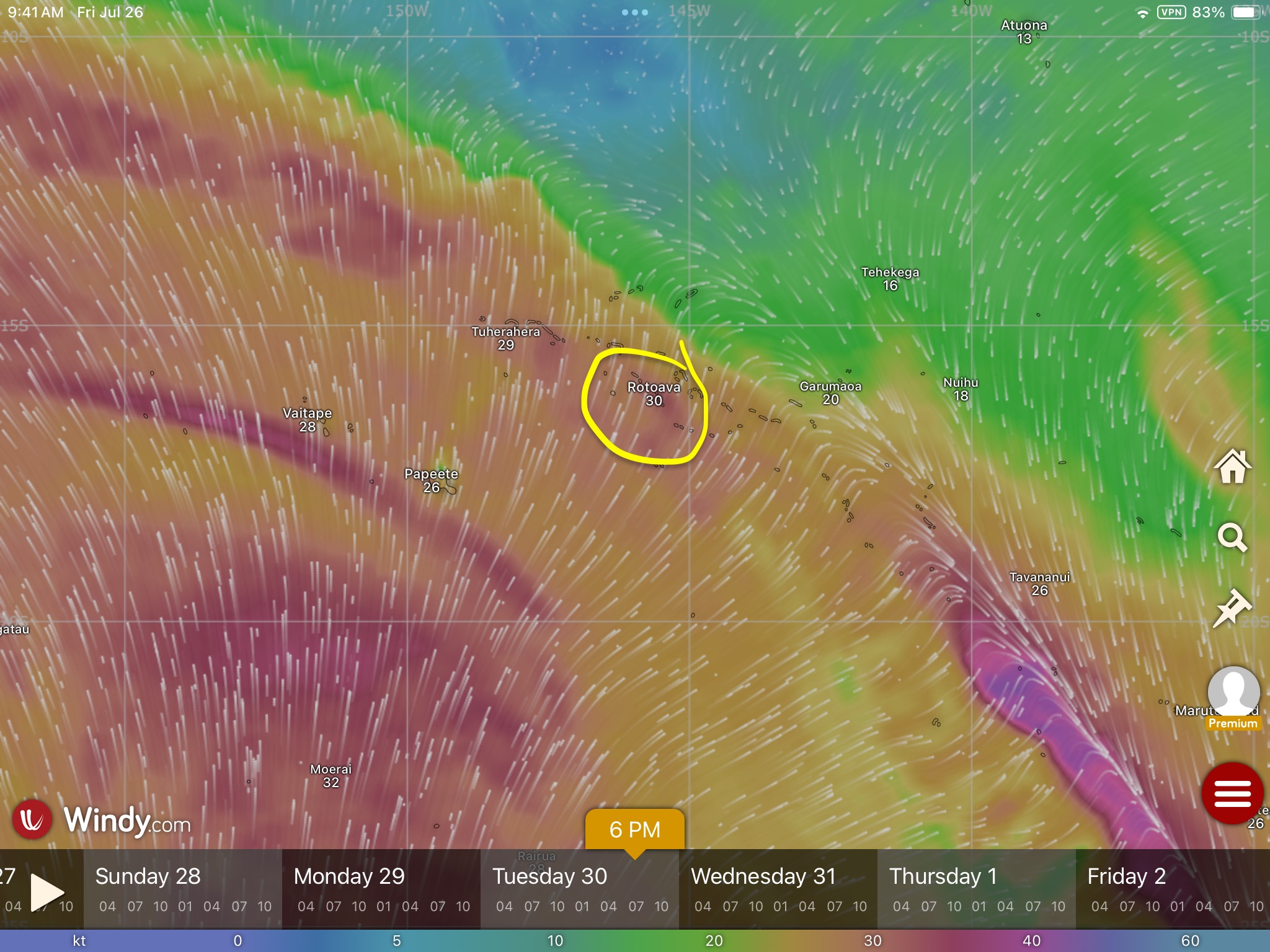

The forecasts had been looking ominous for a number of days. It appeared as though Fakarava was about to be caught right in the middle of the meeting point of two opposing fronts – one coming from the northeast and another quite nasty one from the southwest. It wasn’t that one would prevail – the forecasts predicted they would merge into an ugly mess and the whole thing would press on to the southeast.

The real concern was the squeeze that the convergence was going to cause at our location. We knew we could expect a shit-ton of rain and violent squalls that could kick up winds anywhere in the upper twenties or thirties…maybe higher if we were really unlucky. The big question we couldn’t know until it happened was exactly where the wind would be coming from, when and how it would shift, and how severe would it be on either end. The forecasts gave us an indication, but weather events like these can be quite volatile and unpredictable…the exact shift was anyone’s guess.

At some point, a windward shore was likely to become a leeward shore either way. The best we could do was go with our gut feeling, pick the anchorage with the best holding, be prepared and stay aware.

When it came, it was not pleasant; but not as bad as stories we had heard from other sailors who had experienced similar situations.

Sometimes, when the wind shifts one hundred eighty degrees now putting you on a lee shore, picks up to more than twenty knots, and begins to throw a thoroughly uncomfortable one to three foot fetch that has built up over the entire thirty mile length of the atoll’s lagoon at you, the only thing left to do is pick up anchor, head to the opposite side of the atoll, and await the return of that lazy sunset you were enjoying not that long ago…

…especially when that move puts you back on the doorstep of a village with a restaurant that has scrumptious food, great local Polynesian music, and savory French desserts!

It’s so easy to lose track of time from day to day. And then, before you know it, you realize, “Holy crap, we’ve been here in French Polynesia for two months. We are already down to only thirty days left before we have to be out of the country.”

And just like that, the reality sets in. We’ve only been in Fakarava for less than three weeks but, once again, it’s time to move on. We have two hundred fifty miles to sail in order to reach the Society Islands – not that far, but also, no trivial coastal sail.

So far our trajectory had taken us from the Marquesas Islands to the Tuamotus Archipelago…nearly a thousand nautical miles through French Polynesia. The last group of islands we intended on visiting here were the Society Islands, which included the country’s most globally well-known locations of Tahiti, Moorea, and Bora-Bora. Destinations that evoke not only classic Polynesian images, but represent the actual definition of tropical South Pacific paradise in the mind’s eye of many travelers all over the planet.

We knew Rangaroa, in the Tuamotus, had a reputation as one of the best drift dives in the world for seeing sharks in the pass. After Fakarava, we didn’t doubt that a bit. It was near the top of our list for places we wanted to get to in French Polynesia; however, we were simply running out of time on our visa.

In hindsight, we could have shaved a bit of time off some of our previous stops and just barely slipped it in – but it already seemed like we were rushing. We already were coming to grips with the likelihood that we may not be able to fit Bora-Bora into the limited time we had remaining. We were also facing the realization that if weather didn’t cooperate, we could easily get stuck in Rangaroa awaiting a reasonable weather window for the passage to the Society Islands or, worse yet, be tempted to make poor decisions as we felt the pressure of time squeezing harder and harder.

The weather we had been experiencing in the Pacific was volatile and inconsistent enough that we felt it was inevitable, if we banked on trying to fit in too much, we would come to regret it.

Moorea had been magical for us twenty years earlier, both for diving and in general, and we were in agreement that it was absolutely our top priority. We hoped it would deliver again, dispelling any potential regrets or second guessing we might be saddled with later.

Some boats were headed for Rangaroa; others were headed for the civilization and provisioning oasis of Tahiti.

For Exit, we had decided the heart-shaped island of Moorea was the destination we were making for. About two hundred sixty nautical miles away…the Predict Wind weather router on our iPad estimated two days, two hours.

Even with sloppy conditions, and a temporary holiday declared by not one but both our autopilots Jeeves and Schumacher (Schumacher obviously felt quite guilty and returned rather quickly…Jeeves gave us the finger for the entire passage) we made good time.

After thirty four hours underway we had been sailing almost the entire time, having shut off the engine just one hour after lifting anchor in Fakarava. As the sun set off our starboard bow, we could barely make out the islands of Tahiti and Moorea, staring to come into view on the horizon. We enjoyed a rare toast while on passage to celebrate the twenty-one thousand nautical miles we had just surpassed since leaving Mexico exactly one hundred days ago.

We set anchor in Cooks Bay, Moorea after forty-seven hours thirty minutes…a full two and a half hours ahead of our Predict Wind estimate. In 2003, we had first visited Moorea, by plane. It had been magical. Now, twenty-one years later, we had returned the traditional Polynesian way…by sailboat.

Exit had made it to the Society Islands.