May 27 – June 11, 2024

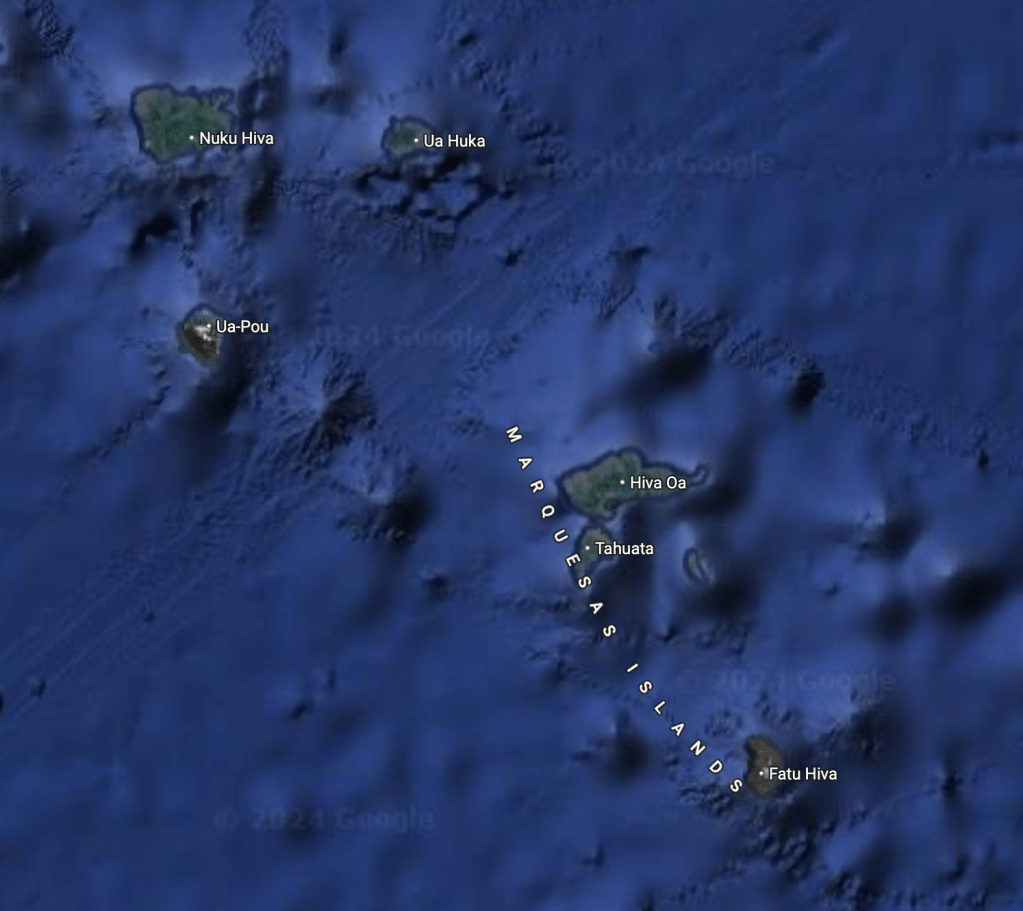

After more than twenty nine days sailing across the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, Exit had successfully carried us three thousand one hundred twenty six nautical miles. Our point of arrival at French Polynesia was Nuku Hiva, in the Marquesas Islands.

Scattered over an area of 1,200 miles in the South Pacific Ocean, the 121 islands and atolls (give or take some smaller islands included with their larger neighbors or that are little more than rocks sticking out of the water) that form the country of French Polynesia are divided into five different island groups – the Marquesas Islands, the Tuamotus Archipelago, the Society Islands, the Gambier Islands, and the Austral Islands.

The Society Islands (by far the most recognizable group which include Tahiti, Bora-Bora and Moorea) – subdivided into the Windward Islands with four high islands and one atoll and the Leeward Islands with five high islands and four atolls – represent almost half of the country’s total land mass and are home to nearly ninety percent of the country’s 300,000 or so citizens.

By comparison, the twelve high islands which make up the Marquesas Islands, almost the same number as the Society Islands group, are only about two-thirds as large and have a population of only about 9,500 people.

The Tuamotu Archipelago, an impressive 3,100 smaller islands or islets grouped into 80 atolls, whose population of 16,000 people is much higher than the Marquesas, has only about two-thirds of the Marquesas land mass, and many of the atolls are uninhabited and inaccessible.

The Austral Islands, with five high islands and one atoll, have about half as many people as the Tuamotus living on about one-fifth of the space.

Similar to the Austral Islands, the Gambier Islands have six high islands and one atoll. With less than 1600 inhabitants it, by far, has the lowest population; however, comprised of less than seventeen square miles of land it also has the second highest population density of the entire country.

Of the 121 islands and atolls that make up French Polynesia as a whole, only about seventy five are inhabited; and, of those even fewer have anchorages accessible or safe enough for Exit.

Still this left dozens and dozens of islands we had to choose from at which to spend the ninety days we had been allotted on our standard visa.

Nuku Hiva and Tahuata – The Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia

Our clearing in process for French Polynesia had actually started before we departed Mexico. Even though we had decided against the more difficult six month visa, our ninety day visa was still complicated with lots and lots of paperwork. In fact, for only the second time since we had started entering countries by sailboat, we opted to hire an agent which cost only about $30. It took a lot of the grief out of the whole process and minimized any chance of mistakes.

After going ashore and completing our official clearing in procedures with our agent and island officials, we had a wander around. Having just completed thirty days at sea, there was no doubt that the ground around us seemed to be in motion; it would take quite some time before the sensation would completely subside. Not land sickness…there was no nausea; just a feeling that the solid land we were standing on wasn’t completely solid. The tipsiness of a phantom ocean motion.

We decided that a bit of food prepared by someone else and a few Hinano Tahiti beers sounded like a great idea. We joked that maybe a few drinks would even help us to walk straight again!

It was already a forgone conclusion that the cost of things would be significant higher in French Polynesia. Of course, this was understandable. After all, we were thousands of miles from anything other than another island. In anticipation, we had stocked our lockers to the brim in Mexico, not just in preparation for the month at sea, but also to try to minimize both our impact on the local inventories as well as our bank account.

Everything we could think of that was packable for long term storage. Canned and packaged meat for me, dried beans, canned veggies and fruit, coffee, canned and boxed beverages, dozens of bags of chips, peanuts, cookies, various treats… and alcohol. Lots and lots of alcohol. We had departed Mexico with only about a case of beer; but we also had more than fifty bottles of wine, one and a half gallons of Jack Daniels, gallons of Kraken rum, gallons of gin, gallons of vodka, gallons of tequila.

After a month of sailing across the Pacific non-stop, thankfully, we had depleted very little of the alcohol stores. But some of the fresh vegetables, almost all of the fresh fruit, eggs, bread, and a number of other things were getting down to a pretty grim level.

Consequently, despite provisioning as though the Apocalypse was arriving (as we always do), we ended up experienced a rather stunning case of sticker shock as we actually began to make purchases…a loaf of bread $8; a six-pack of beer $21; any fresh fruit or veggies (what could be found) quickly racked up at least $10 per bag; and some commodities had caps on how much you were allowed to purchase (no more than two dozen eggs, for example). Yikes!

Another striking distinction from what we had become accustomed to in Mexico, was the overwhelming abundance of green. There was no doubt we had made a drastic transition in landscape.

For two years, we had become used to the browns, reds, pale yellows, and grays, characteristic of the Sea of Cortez, which represented a harsh and unforgiving climate almost completely devoid of moisture. Drought riddled parched earth, scrub brush, low-lying twisted bushes and yellowed grass. Green was a color reserved mostly for the hardy cactus – gnarled, scarred and weathered, armored with menacing needles and spikes instead of leaves.

Now, we could actually smell the dank and pungent odor of wet dirt. The endless shades of green that comprised the foliage covering the island were a complete contrast to Mexico. Rain was obviously no longer an event counted on fingers in a year; it was daily way of life.

Within a few days after our arrival, we felt fairly rested up and had re-stocked some of our depleted provisions. It was time to do some exploring.

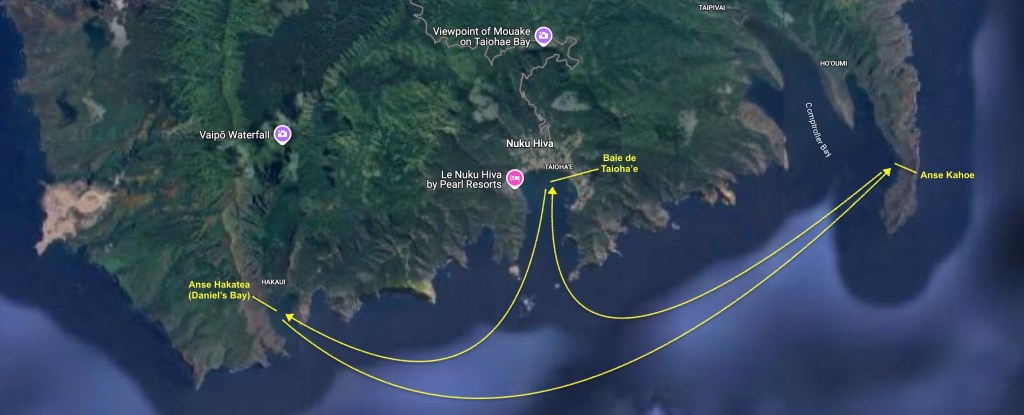

We left Baie de Taioha’e and sailed six mile west to an anchorage called Anse Hakatea (or Daniel’s Bay).

A few days later we sailed ten miles east, past Baie de Taioha’e, and dropped anchor at Anse Kahoe. Then back to Baie de Taioha’e, followed by another return to Daniel’s Bay.

The Marquesas Islands are the first French Polynesian island group one encounters when sailing from Mexico and so, after such an epic distance, it was an obvious place to begin our exploration of the country. There was no doubt, the landscape was breathtaking and the people seemed incredibly friendly. However, we had a lot of area to cover within the duration of our limited ninety day visa. Consequently, after a week bouncing between the three different anchorages on the south side of Nuku Hiva we concluded that it was time to move on.

The distance between Nuku Hiva and Hiva Oa (the other main island in the Marquesas group) was about eighty-five nautical miles; a bit more than a day sail for us, but an easy overnight passage.

Hiva Oa is probably the most popular place to clear in, but we didn’t like the prospects of its anchorage nearly as much so we had chosen Nuku Hiva to clear in to the country. Having already accomplished that, combined with the knowledge that there would probably be a lot of sailboats just hanging out in Hiva Oa, we concluded that we preferred the smaller island of Tahuata as our destination. It was right next to Hiva Oa, making it essentially the same distance.

We picked up anchor just before noon on June 7 and, after a very relaxing mostly downwind overnight sail that ranged between twelve and twenty knots, we arrived at Tahuata just after sunrise. A short time later we were enjoying breakfast beers at anchor in Baie Hanamoenoa.

After two days, which included a very quiet and uneventful birthday for me, we moved to Baie Hanatefau, five miles to the south.

Baie Hanatefau provided not only a postcard perfect backdrop to anchor in, but also a very protected bay with absolutely flat surface conditions.

This allowed us to address our wind indicator sensor atop the mast, which had been out of commission for a month. Having it die midway between Mexico and French Polynesia had been, to say the least, less than ideal. We had ended up sailing sixteen hundred miles without it, which had reduced the accuracy of our data interpretation for sure.

Not that it wasn’t possible to still observe what direction the wind was coming from using the old school optical sensors we had been born with, as well as having some rough sense of wind speed by combining what we were seeing on our weather forecasts with the real-time data verification of the likewise old school technology of the licked finger in the air sensor.

Still, it was nice to have a better indication of wind than: not enough, just right, or too fucking much. And even nicer to have it clearly and conveniently available on a display in both the cockpit and at the nav table.

Hence, another trip up the mast. Fortunately, this time in perfect conditions – at anchor in flat water with enough clouds to prevent the sun from cooking me yet not enough to unleash a torrent of rain and/or lightning.

We were relieved to learn, as is often the case, our wind sensor failure was the result of nothing more than a bad connection. Inconvenient, no doubt; but not catastrophic. Sometimes, it just gets lonely up there all alone, I reckon, and wants some attention.

Amazingly, we had fared very well with all our equipment considering the more than three thousand miles of exposure to all the elements and stresses the Pacific Ocean had subjected Exit to. Outside of the wind sensor, we had only temporarily lost our autopilot Jeeves (also probably an intermittent connection gremlin), had our genoa furling line destroyed in a squall (which had already been sorted), as well as two blocks on our preventer line (which prevents the boom from experiencing an uncontrolled gybe) having failed. But both blocks were rusted and exploded simply due to wear and tear, so we kind of had that coming anyway.

These had already been replaced by massive solid aluminum blocks we found in our spares locker which appeared rather bulletproof – it seemed to me that the boom would fail before these things would.

Getting the wind sensor at the top of the mast figured out meant we were back to 100%…or as close as you could ever ask for on a boat.

Which also meant we were good to go for a longer passage than day sailing or overnight island hopping.

Though we had been in the Marquesas for less than two weeks, we wanted to make sure we had plenty of time for what lie ahead. We had made a fairly firm decision to omit both the Austral Islands and the Gambier Islands groups from our itinerary. Had we arrived earlier with six month visas we may have approached things differently. However, after much research and discussion, we felt confident that the Tuamotus Archipelago and Society Islands would ultimately be where we wanted to concentrate our time. These, we felt, would be the places offering the most enjoyment and adventure.

At just over four hundred nautical miles distance, we expected it to take us three to four days to reach the Tuamotus Archipelago.

And so, with forecasted east winds in the twelve to eighteen knot range and fair weather expected, we set sail for the tiny atoll of Raroia.

Of course, we were learning quickly that forecasts in the middle of the Pacific were at least as inconsistent as we had come to know in the Sea of Cortez.

When we finally got our easterly winds, eighteen hours after departing Tahuata, they punched us with twenty four knot gusts. For a time, we saw more waves and spray make their way onto our dodger than ever before.

Just after sunrise on our second day, we experienced what appeared to be a union strike. Jeeves, the autopilot, and the wind indicator at the top of the mast (yes, the one we had just got working again) both decided to walk off the job. It was just going to be one of those passages.

While our displays were down, our only crew member “Slo-T.H.”, seen in the previous photo resting in front of the displays, maintained a constant watch. For over 10,000 nautical miles – ever since Kris found the carved wooden sloth floating at the surface while paddling her SUP near the Bocas del Toro mangroves in Panama during Covid, Slo-T.H. has maintained a 24/7 vigil in that location.

The following afternoon we sailed between the Disappointment Islands. Apparently the natives encountered there some two hundred fifty years ago by John Byron, the British explorer who named the islands, were quite hostile to the idea of being conquered, colonized, or generally molested – hence the name. Not surprising, as far as I’m concerned. We didn’t find the islands disappointing at all. But we didn’t try to invade the few hundred residents, either. Just passed right on by.

Ironically, we later learned, a sailboat that made the same passage a month or so after we did, had a quite different experience, and definitely concluded the Disappointment Islands to be aptly named. It turns out, if you don’t zoom in and magnify electronic charts far enough, you lose some degree of detail. In fact, some landmarks fail to even register on the screen – a detail which, for us, has resulted in our painstaking practice, without exception, of zooming in closely along the entire route of any plotted course we are on.

As it so happens, this other sailboat may have failed to note that digital chart quirk…apparently failed to note the existence of the Disappointment Island…and obviously failed to sail around them, opting instead to sail right into them. Ouch. We never found out whether the boat eventually got off the rocks or was lost entirely. Regardless of the circumstances, avoidable or not, an undisputedly tragic situation not to be wished upon even one’s worst enemies. There but for the grace of Neptune goes Exit.

Conversely, for us the passage had been as good as we could have hoped for. Despite the electronics setback with Jeeves and the mast wind indicator, which turned out to be a short lived union strike that was resolved by somehow placating the Gods of Electrical Voodoo, we had made excellent time. Overnight, as we approached completion of our third day underway, we actually had to slow our approach for the final thirty miles so as to avoid arriving at Raroia before sunrise. Another one of our conservative and sometimes inconvenient strategies to avoid running into things – don’t enter unfamiliar anchorages or passes, and don’t navigate through risky waters at night.

Occasionally you have to avoid all of the above at the same time.

The Tuamotus Archipelago is made up of atolls – peaks of inactive volcanoes which over time have eroded to sea level, filled with water, and eventually become enclosed lagoons surrounded by fringing reefs and/or narrow bands land. The land surrounding the lagoon, comprised of volcanic rock, sand, and dead coral may only be tens of meters wide and sections cab be completely submerged during high tides. Typically there is some sort of folliage – palm or various species of trees, bushes and tangled ground cover.

Though the land making up the atolls can be minuscule, the overall area that the atolls occupy can be quite large; hence, the volume of water inside the atoll lagoon is massive.

The atolls themselves range in size, shape, and depth; but most have some sorts of breaks in the reefs which may or may not permit vessels of various sizes to enter. Most have shallow bommies, shoals and small islets scattered inside which offer varying degrees of navigational risk. Many are inhabited.

With the light of a new day we were treated to the experience of sailing towards a rainbow.

Shortly afterwards we were introduced to our first atoll in the Tuamotus…Raroia.

To be continued…