July 10, 2024

In the Marquesas Islands of French Polynesia, the anchorages in Raroia had been good holding and we had been able to find pretty clear sandy patches. However, during our research before departing Mexico, we had learned that many boats in French Polynesia (especially in the Tuamotus Archipelago) chose to use a technique called “floating their chain” to help avoid issues with anchor chains getting wrapped around coral bommies. An anchor chain hung up or wrapped around coral can result, not only in the destruction of delicate coral but also in, at best, inconvenient hassles to free the chain and, at worst, dangerous situations for the unfortunate boat and crew.

Upon first hearing the term floating the anchor chain, our response had been, “Huh?”

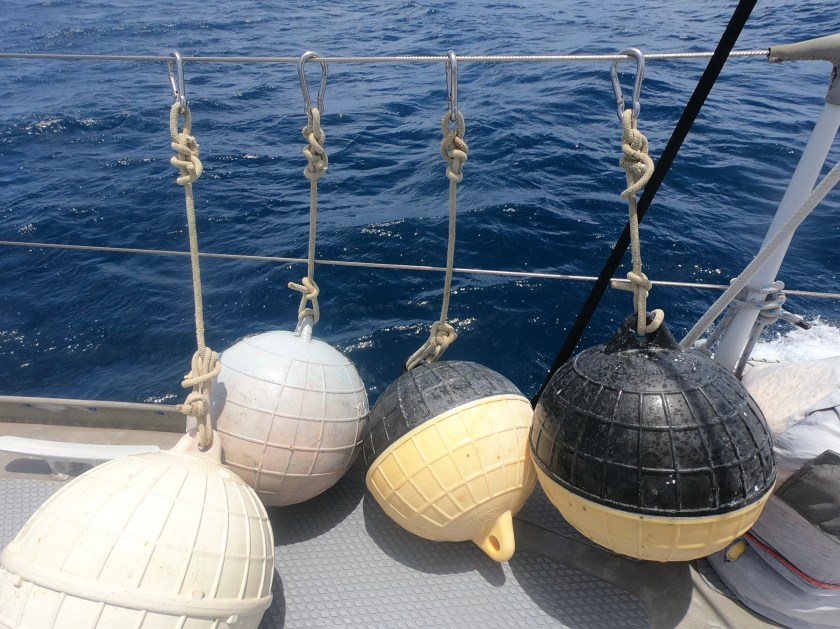

We had further researched the concept and technique and, in Raroia, had actually purchased three hard plastic floats for ten dollars each from a local guy who was the caretaker at an abandoned pearl farm we visited in our dinghy near the Kon Tiki anchorage.

The plastic floats are abundant in French Polynesia – not only being used in the pearl farm industry, but also by fisherman for nets, as markers for navigation or moorings, and even as yard decorations in the villages and towns. We had heard that the savvy or frugal sailor could simply wander the leeward beaches after a good blow and stumble across them regularly. We did obtain two additional floats this way, but ultimately found the caretaker at the abandoned pearl farm to be a much more simple and reliable source.

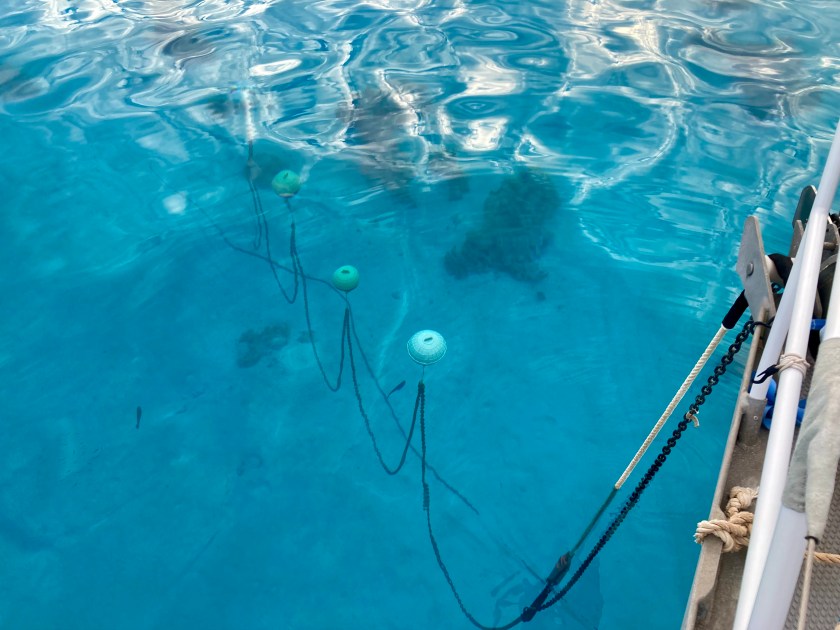

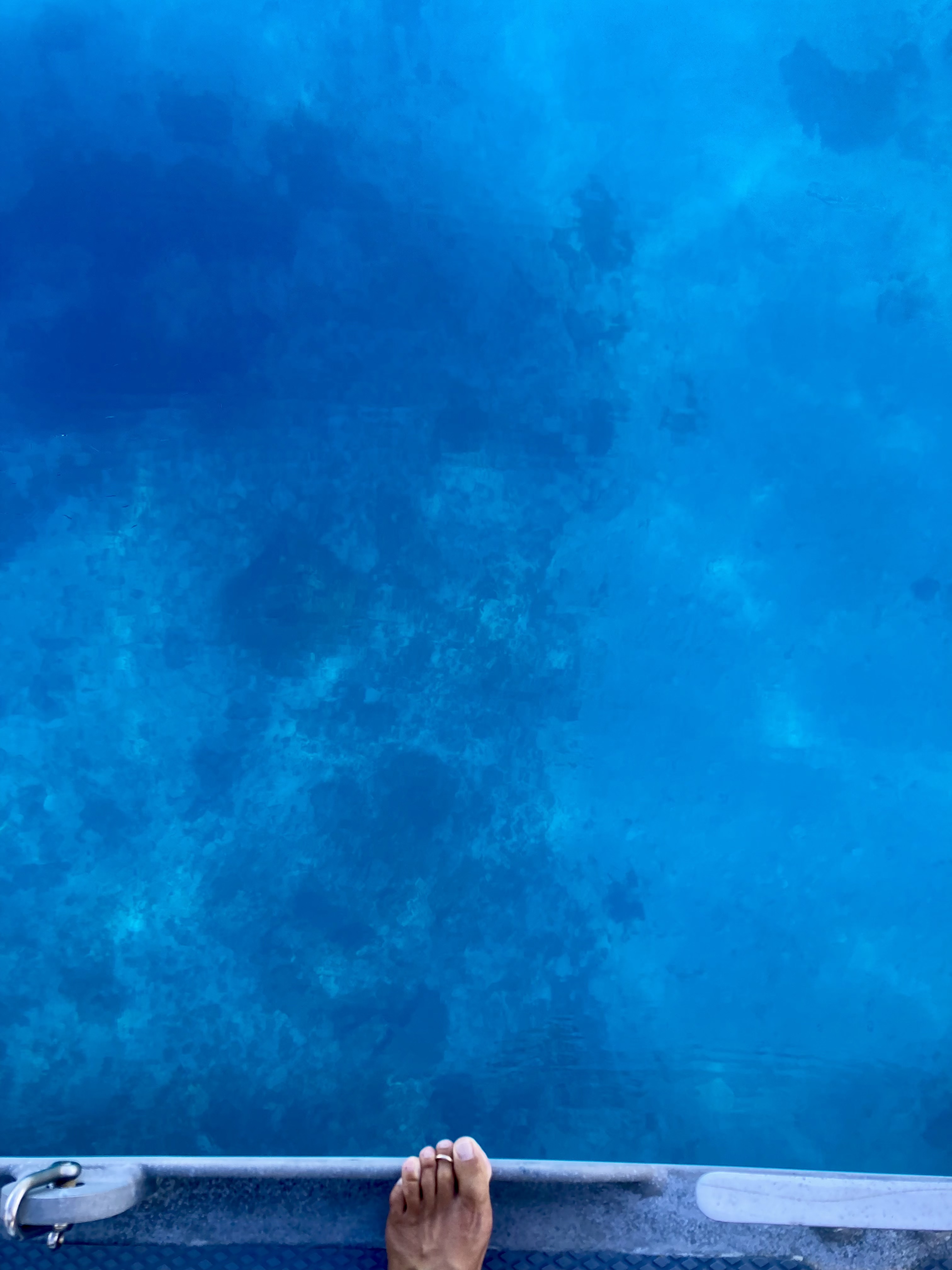

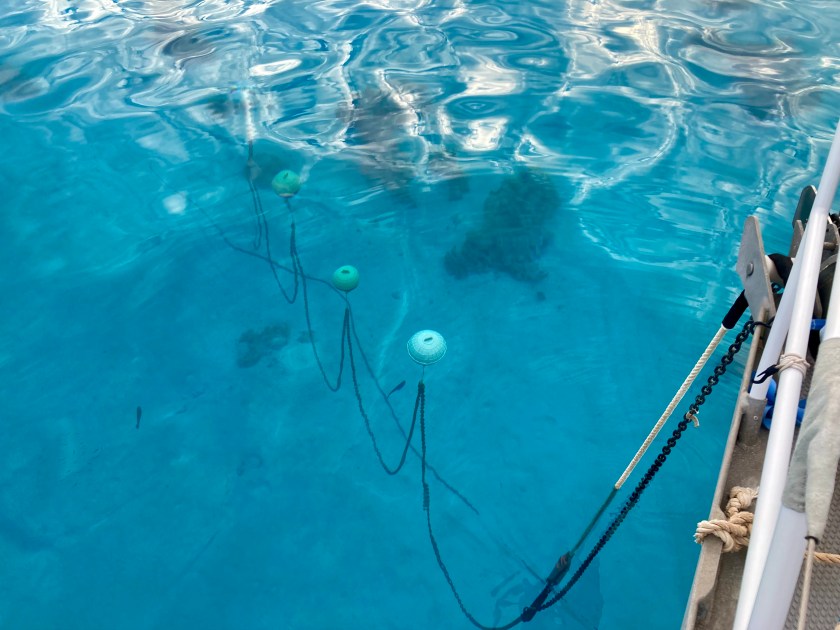

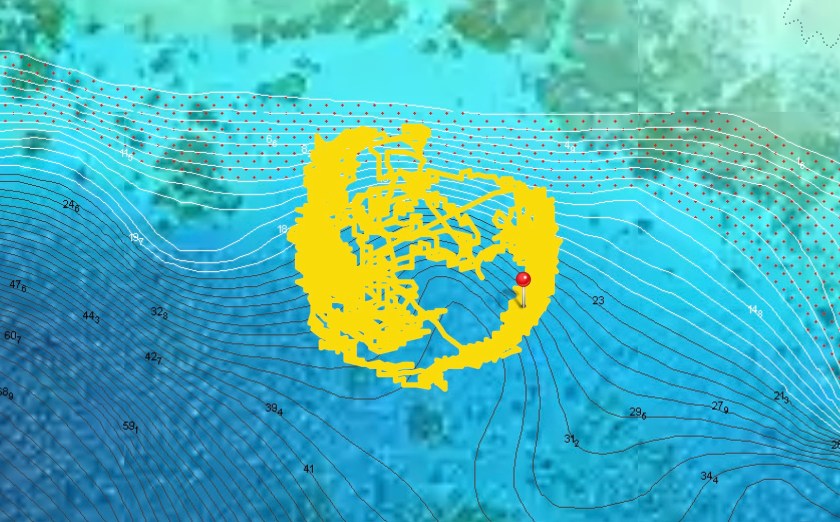

Once we had arrived at the anchorage inside Tahanea’s lagoon, looking over Exit’s toe rail into the crystal clear water, it immediately became very self-evident why this chain floating technique was needed.

We were going to have to sort our shit out. And as is often the case aboard a boat, that shit needed sorting sooner rather than later.

Simply deploying our anchor chain as we always had, would be the easy way out, but obviously here it would very likely lead to major issues.

It took a bit of time and a few tries to sort out all the logistics and variables. But very quickly we were sold on the technique. We would later conclude, even though we constantly heard other sailors asking about where they could get rid of their floats upon leaving the Tuamotus, that keeping the floats was a prudent idea and we found ourselves using the technique constantly even after departing French Polynesia.

As with any decision or strategy, all but the most foolish or naive understand that everything is a compromise of some kind. Advantages or benefits are always going to be accompanied by disadvantages or limitations.

Many boats don’t even consider the damage they can cause, not only by dropping their anchor right on top of something, but also by their chain dragging across the bottom while at anchor. Even in unobstructed patches of sand, there are endless numbers of marine creatures that can be disrupted and unseen ecosystems that can be decimated. In the case of hard coral, which may only grow at a rate of centimeters per year, an anchor chain that wraps around or sweeps across the top of a bommie can kill marine life that may take years to recover. Soft coral, sponges and other more delicate organisms may be wiped out completely. And with the destruction of these structures, comes the displacement of anything else which may be living there.

Even if you choose to completely disregard the potential damage to marine life, there remains a real risk to your ground tackle or the boat itself. Chain rubbing on rock and coral is bound to incur damage, not only to the galvanized outer layer, but also to the metal itself. Nylon rode can be chafed completely through in a manner of hours.

Getting wrapped around or caught on something at the bottom can be even worse. Even high tension half inch chain can snap if a boat finds itself on a short scope after becoming wrapped around coral bommies, rocks, or other obstructions in storm conditions which may bring high winds and/or building seas. And even if the chain doesn’t break, a damaged or destroyed bow roller or bow sprit, or a windless that rips clean off the deck can leave you in an equally big world of hurt.

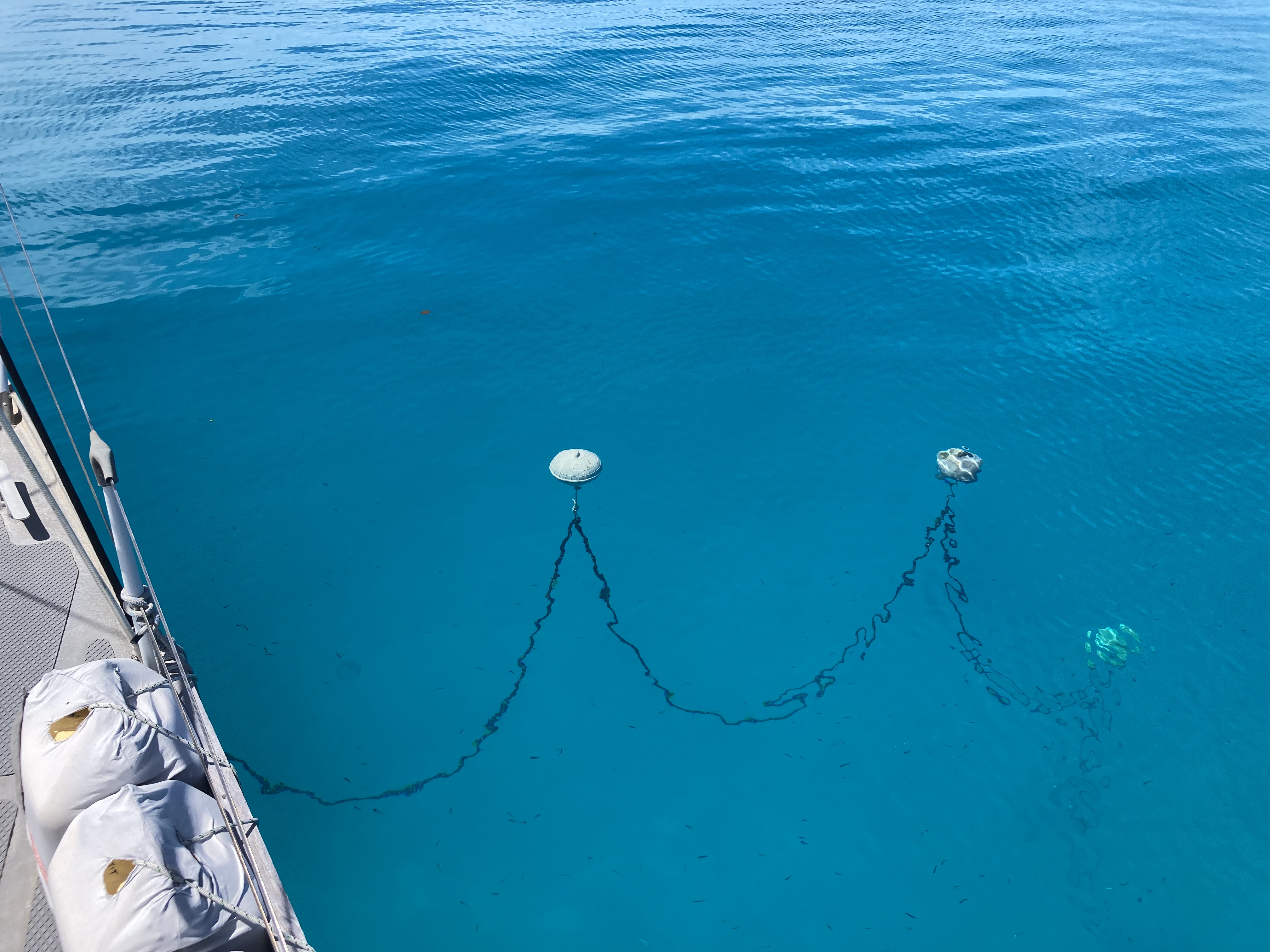

The strategy of floating the anchor chain is to get as much chain off the bottom of the sea floor as possible.

Others try soft inflatable fenders, but hard plastic floats seem much easier and more consistent to work with. The buoyancy of inflatable fenders will change depending upon the depth they are at. Consequently, others who tried to use inflatable fenders complained that either the fenders were just sitting on the bottom (not doing much at all) or they constantly had to adjust how much chain was between each fender depending upon the depth the fender ended up at. If the fenders are large enough, I suppose they could just be floated at the surface and the length of the line attached to the float could be adjusted, but that seems like much more of a hassle.

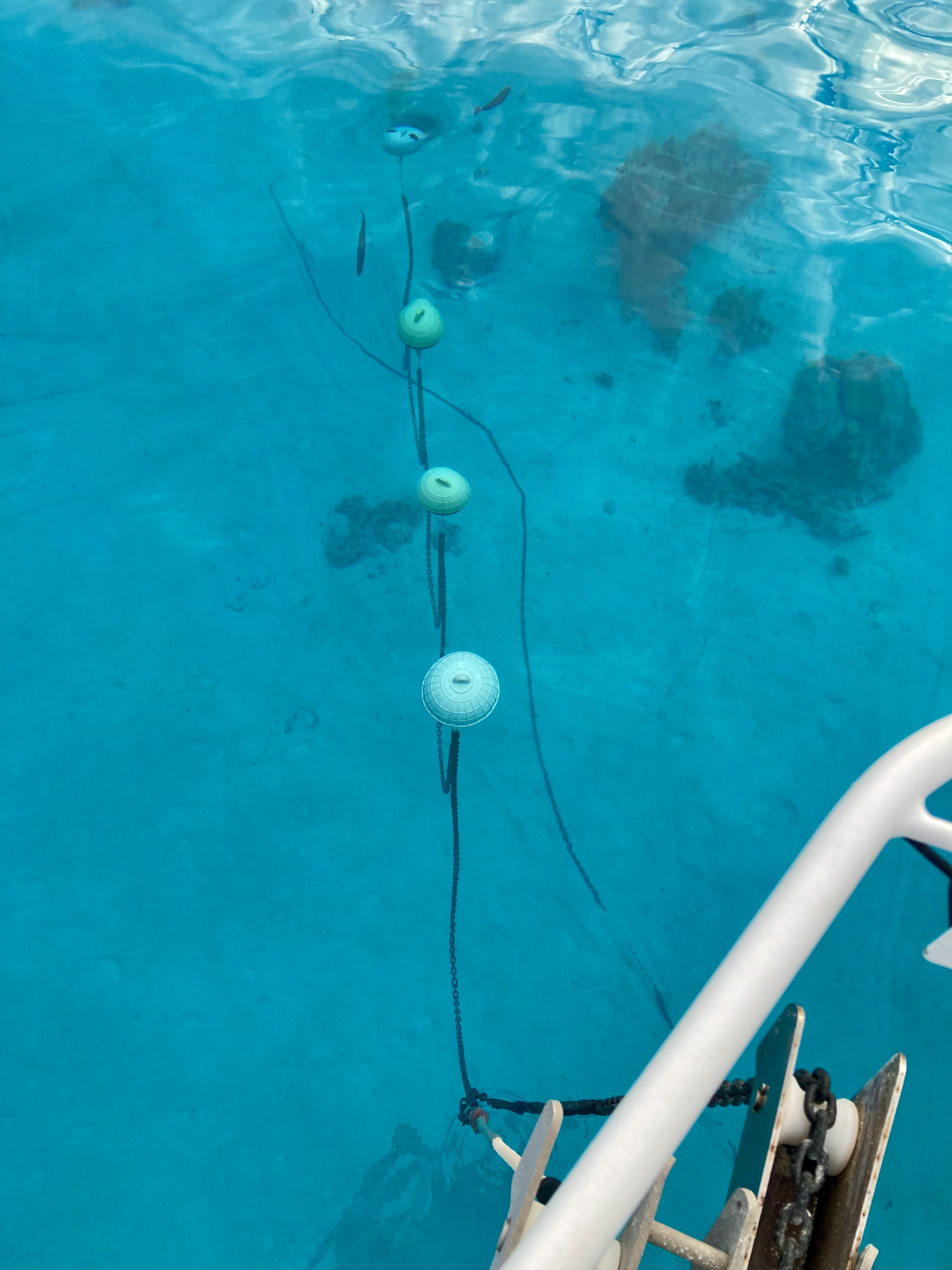

We had a foot or two of 3/8″ nylon line with one end tied to the hard plastic float and the other end attached to a shackle that clipped directly to one of the links of the chain. Cheap clips corrode and wear quickly and the springs don’t function for very long at all. However, we found a bit more investment in a good quality stainless steel clip provided a durable connection that was very convenient and easy to clip and un-clip to the chain.

To float the chain, as with any anchor spot, our strategy is to first to try to locate a bit of sand with good holding to set the anchor. In a perfect world, it would be completely clear of obstructions 360° around the spot the anchor was being dropped for a diameter twice the depth of the water. For example, if we were anchoring in twenty five feet of water, we want a clean sandy patch a minimum of fifty feet across. This would give us at least 2:1 scope of clear space as a starting point.

However, we find a 2:1 scope generally is not adequate for us to get a good initial anchor set. Oftentimes, the anchor drags and slides across the bottom without digging in. If the open area is bigger, great. If not, we try to orient Exit into the wind while aligning ourselves on a clear path as we approach the spot at which we actually drop anchor. Even if there are some coral bommies, rocks, or obstructions in the area, once we drop anchor and start drifting backwards with the wind or reversing engine, the chain will usually temporarily orient itself along the clear path we have just established.

This allows us to pay out enough chain to get a good set; more like a 3:1 or 4:1 scope. We can now set our ground tackle just like we would if we weren’t going to float the chain. We have a short snubber attached to the samson post at our bow that we clip/unclip on the chain as needed to absorb any shock loads until after everything is set; then we finally attach the regular snubber in the end. Once we have backed down at 2000rpm and are happy with the anchor set, we pull the chain back up again until we are somewhere around a 2:1 scope.

Now the first float can be attached. Then a bit of chain can be let out and the process repeated.

Obviously, the size of hard plastic float as well as size and type of anchor chain has an effect on float placement. We found with our 3/8″ G4 chain and the floats we acquired (about 13″ diameter), we were able to get the floats and chain oriented at a good depth with about 20-30 feet between each float.

If there is no wind the first float should be sitting at least five or so feet off the bottom. In twenty five feet of water, we would attach the first float at around 50-60 feet of chain; the second at around 80 feet; the third around 100 feet; the fourth at about 120 feet; and the 10-15 foot snubber at around 140 feet which would give us a final scope of 6:1.

Depending on the depth and the intended final scope, more or fewer floats can be used in conjunction with more or less distance between each float. In some conditions we found with 150′ of chain out, three floats actually worked better with a bit more chain hanging between each float and the floats sitting a bit deeper in the water.

The biggest concern we initially had was whether floating the chain would compromise our holding capability based upon the fact that there would not be as much chain on the bottom. Earlier, our mindset had often been the more chain on the bottom the better. While generally true, this doesn’t reflect potential damage that may be inflicted or limitations based upon surrounding obstructions in the area.

We found the cantilever effect of floating the chain seemed to be about the same as if there was twenty knots of wind. If there was any real breeze with the floats in place, there would be very little chain on the bottom at all, so we weren’t getting really any added holding from the weight of the chain. Without much breeze at all, there would always be that first 2:1 scope of chain on the bottom. As long as we were well set in good holding, we felt comfortable. If the anchor wasn’t set well enough that it would drag in 20-25 knot winds without the floats, we considered that a recipe for disaster anyway.

With very few exceptions this configuration helped immensely to avoid dragging over the top of or getting wrapped around coral. As Exit swung around, the suspended chain passed right over the top of any obstructions below it. There were numerous instances we watched other boats having to reset or move to an entirely new location with any changes in wind direction. Just as often we watched boats dealing with the misery of trying to raise anchor, only to realize they were hung up on something, oftentimes in the worst of conditions.

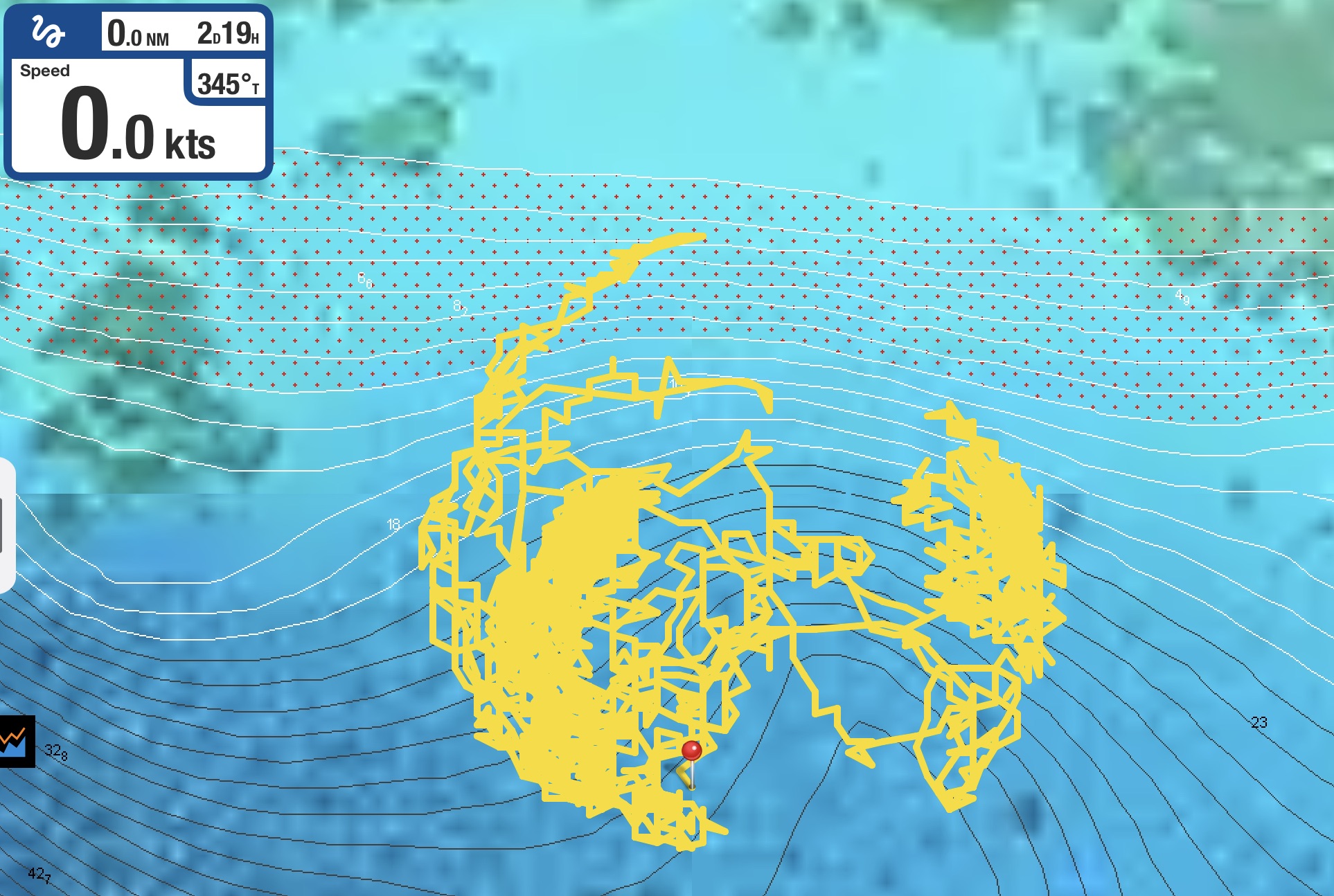

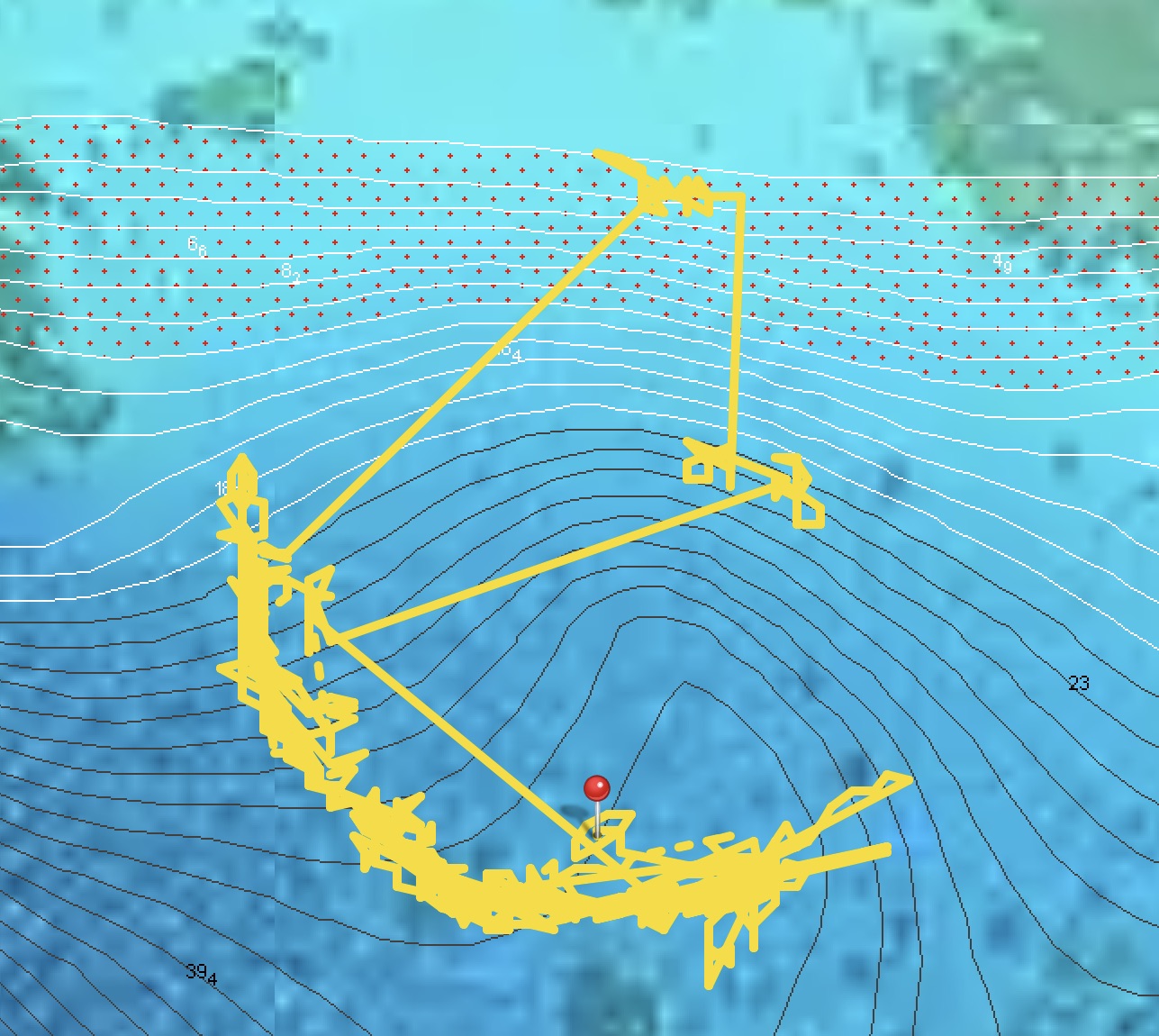

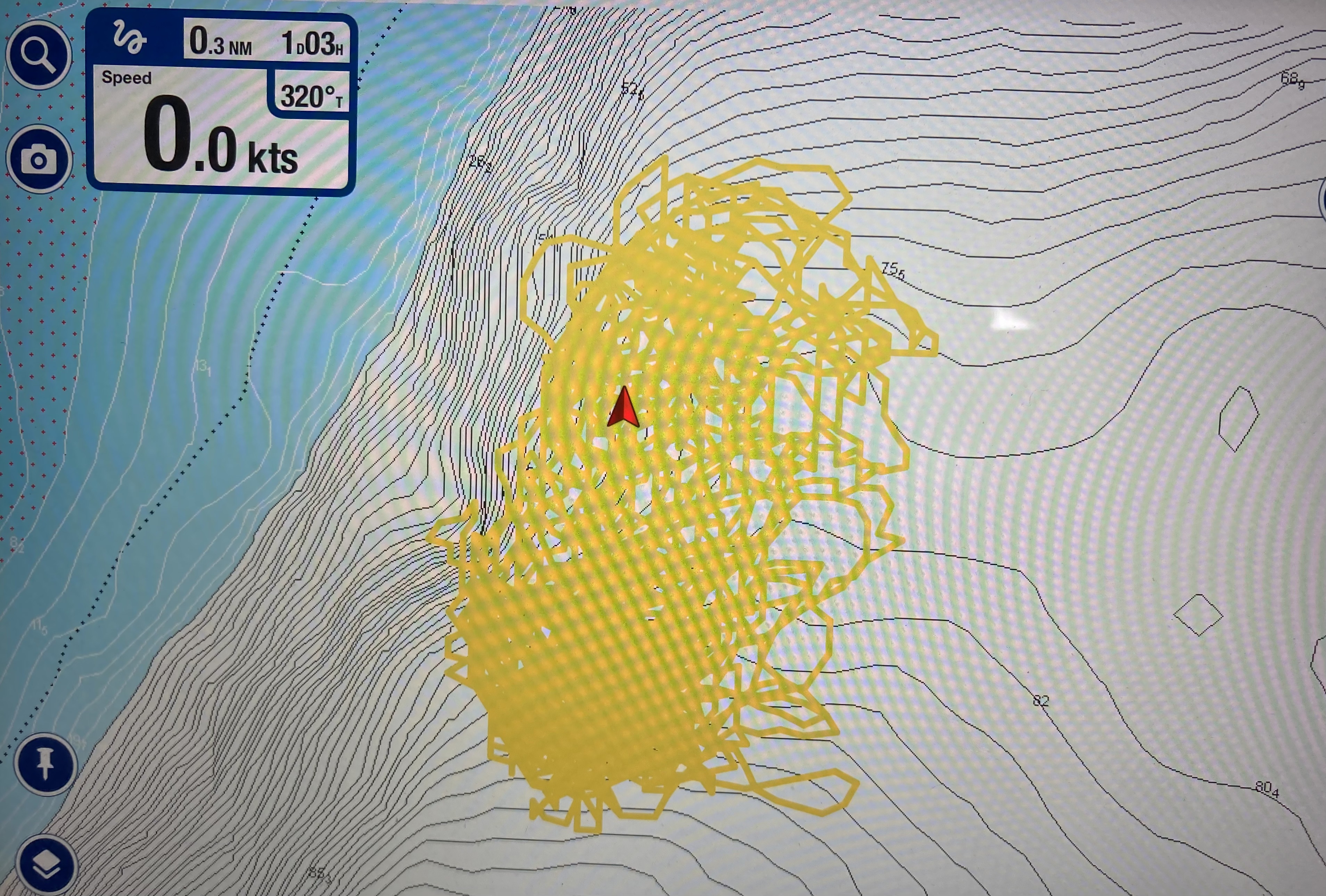

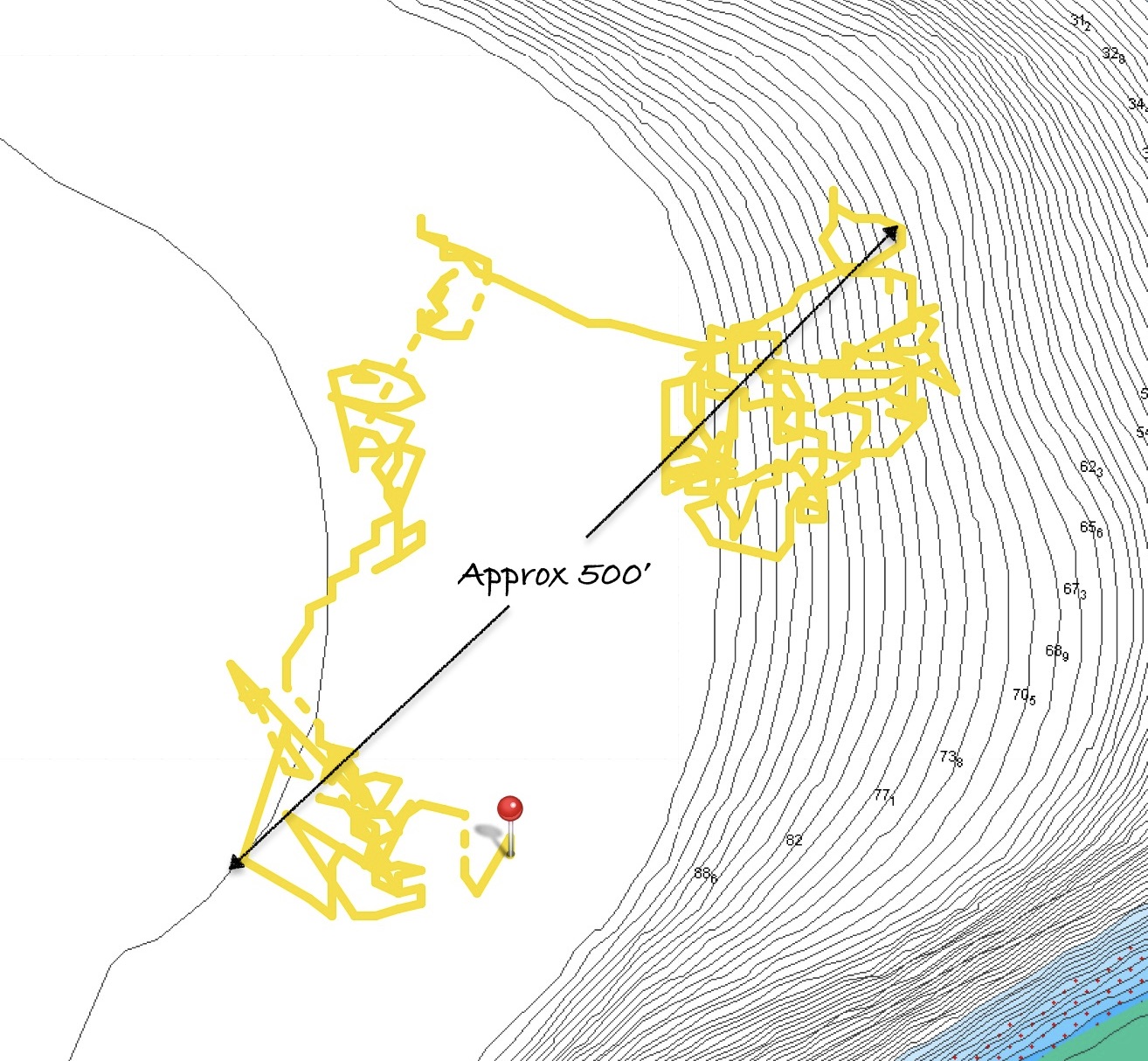

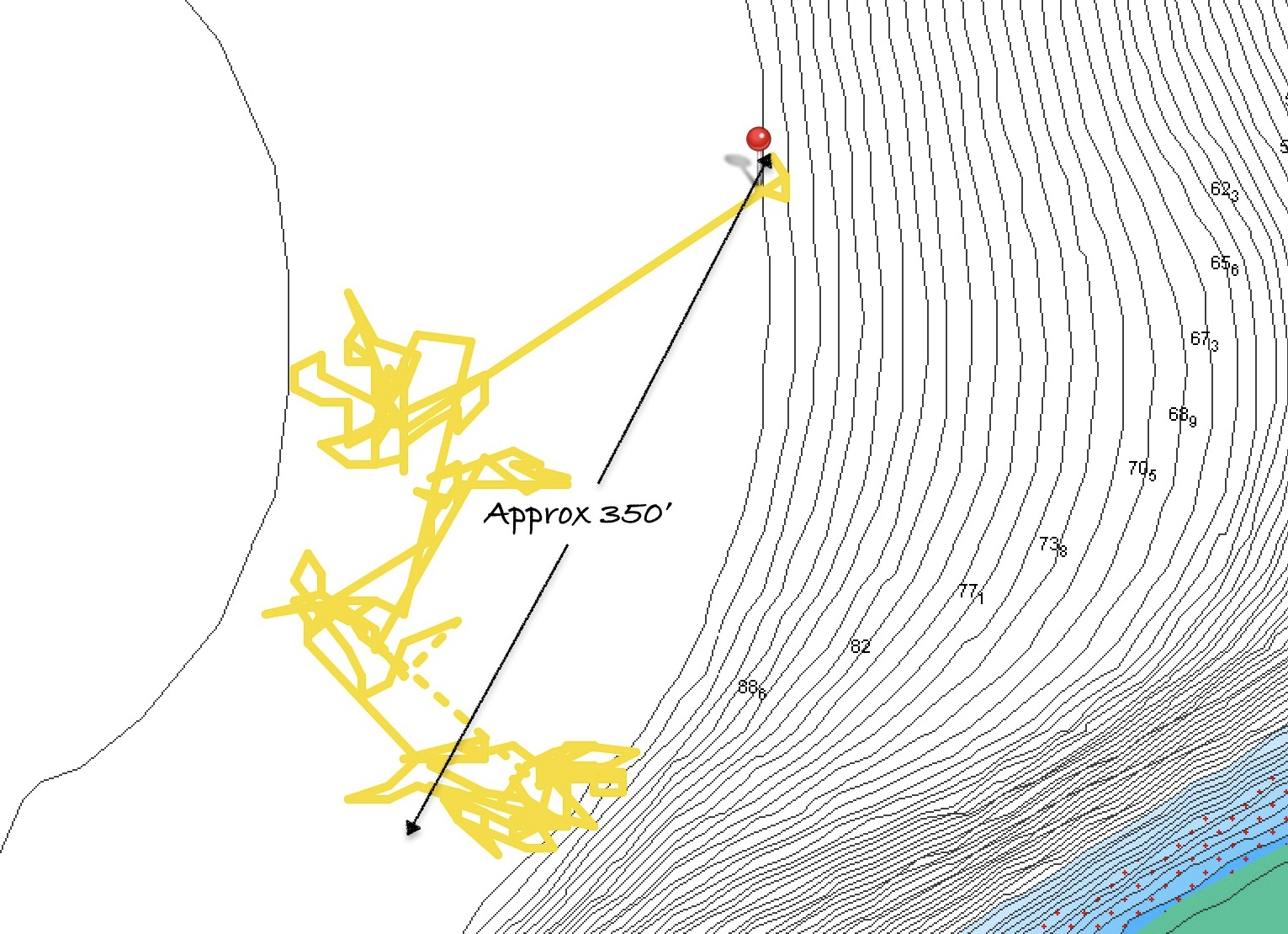

Without any doubt, having the chain floating off the bottom meant that Exit moved around more than if the chain was sitting on the bottom. A LOT more. In fact, many times we would find the anchor track circling completely around the anchor point over the course of a couple of days, especially given the influence of changes in wind direction, squalls, and current changes. Still, as long as we had that 2:1 scope of clear sand around the anchor, we could circle the anchor with a hundred feet of chain passing over the top of dozens and dozens of coral structures without a single problem.

The only time this wandering about becomes problematic for us is if there are obstructions within close proximity of the anchor. We found a handful of times, that the extra movement and drifting allowed by the floats could cause us to drift closer to these obstructions without the chain clearing over the top of them. In these cases, the weight of the chain on the bottom actually keeps us in place and out of the way of obstructions that we may pass across if the chain is being floated. As long as we are sitting clear of the obstruction, this is one situation where not having the floats out makes more sense.

Exit tends to hunt around a lot at anchor anyway, possibly because of our centerboard configuration, especially in gusting winds. When this was happening, we found a lot of the shock loading that we could experience as the boat reached its limit in one direction and turned back the other way was drastically reduced when our chain was floated. It acted as a bit of a snubber for the whole length of deployed chain, softening the loading or making it seem a bit spongier. This was truly an unanticipated benefit.

When the winds completely died, there were a few things we needed to be cognizant of. Without a breeze or currents pulling the boat at all, the floats may end up sitting on the surface, or just below. It some instances this can result in the floats actually banging against the side of the hull…minor, but an annoyance to say the least, especially at three o’clock in the morning. More serious can be the risk of floats being struck by passing boats. If the floats are actually on the surface, they can usually be seen; but submerged barely below, they can be almost impossible to notice before its too late, especially if the water is a bit choppy or a boat is passing close by and moving fast.

A problem we encountered a couple of times was having the chain, snubber, or floats becoming entangled with each other. If the boat drifts around a bit and the floats all congregate next to one another, the slack hanging down can get wrapped around one of the floats. Again, only an annoying inconvenience if it is noticed while there is still slack in everything.

But a couple of times we had a squall blow through or the wind picked up before this was noticed. Once we ended up with the snubber tensioned up around a middle float with fifty feet of chain and another float still slack between the tangled float and the boat; another time two of the floats were tangled together. Fortunately, even the 3/8″ nylon line we had attaching the floats to the chain was strong enough to hold. We were able to sort things out before the line parted and we lost a float or had bigger problems emerge. Still, it was literally a massive ball-ache to deal with.

Still, much more often than not, we were glad to be floating the chain. Later, once in Tonga and once in American Samoa, we experienced the two worst case of anchor chain fouling we had ever dealt with in over seven years. One was in over fifty feet of water; one was in nearly a hundred feet. In both instances, we were not floating the chain.

We experienced many instances where boats nearby found themselves hopelessly wrapped around coral bommies, even having to eventually dive their chains to free them. Numerous times we watched frustrated boat captains motoring around an anchorage looking for adequate open space to anchor. Even more often we saw boats make two, three, four, even five repeated attempts to anchor in limited space. Sadly, more commonly than anything else, we saw boats drop anchor without the slightest concern whatsoever for what was underneath them; completely oblivious to the damage they were obviously causing.

In sustained winds of thirty knots gusting into the upper thirties, both during harrowing squalls that jumped from four to thirty-four knots in one puff as well as consistent blows that lasted for multiple days, sometimes with winds funneling down from highlands or through valleys causing erratic shifts in wind direction, the floats never caused our Rocna 33kg anchor to drag.

We successfully used the floats anchoring at depths ranging from twenty to a hundred feet.

Removing floats in response to changing conditions was certainly much easier than having to lift the chain to put on floats we later deemed necessary. The floats can be removed quite quickly even by free diving down to them. On the other hand, the floats definitely can’t be pulled down to attach to the chain underwater, even with scuba gear.

Some time later, after departing French Polynesia, while anchored in a hundred feet of water without any way to see what was on the bottom, on multiple occasions we managed to successfully use the four floats with our entire 350′ of chain we have aboard out. We estimated there was never more than one hundred feet of chain on the bottom. It appeared to us that, even with our anchor track drifting across a diameter of 300-500 feet, we never hung up on anything. Each time, the anchor chain came up without an issue.

Out of fifty different times anchoring in probably forty different locations, we found floating the chain beneficial in all but a handful of instances. We only had two situations in which we had deployed the chain floats where we subsequently decided we needed to remove them.

After understanding the limitations of floating the chain and a few of its quirks, we have become absolutely enthusiastic advocates for the technique. Its advantages outweigh the disadvantages in almost every case.

As temporary visitors to an area, we have an absolute obligation to do everything possible to minimize the impact we create and reduce risk of damage whenever feasible. As sailors, sea gypsies, and offshore residents, it is imperative that we embrace our role of ocean stewardship and make every effort to protect the marine life around us. It is a minimal courtesy we can extend to our neighbors and fellow marine inhabitants.