November 25 – 29, 2024

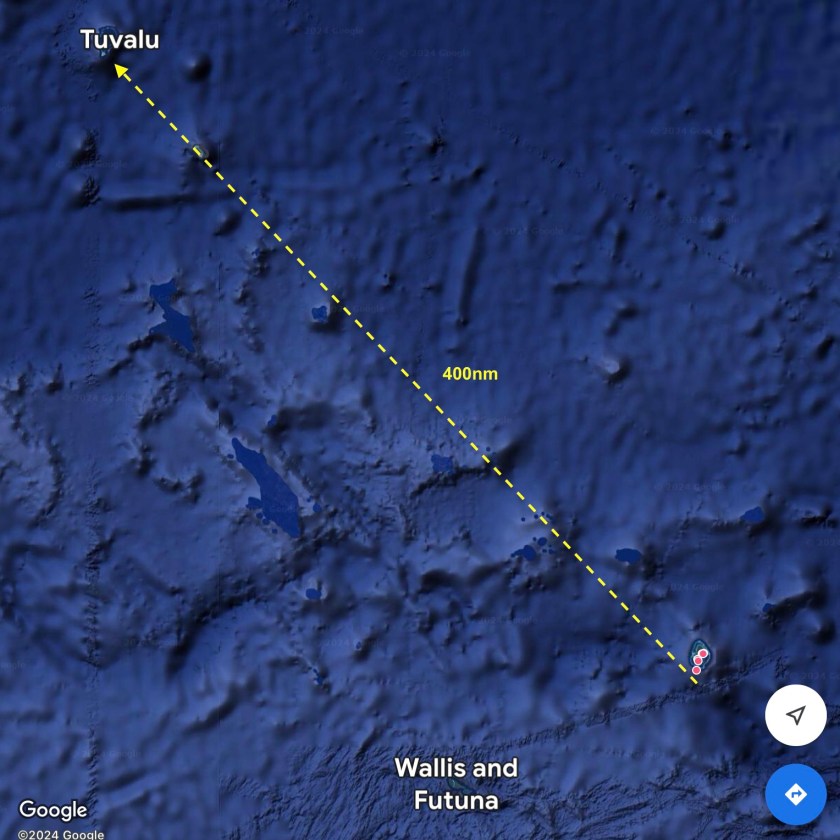

Three to four days was what we anticipated the four hundred nautical mile passage to Tuvalu would take us. The forecast wasn’t great, nine to twelve knot winds from the east, but it seemed about as good as we could hope for given what we had been seeing for the previous weeks.

In actuality, it ended up being more like four to six knots…and from the south. So much for accurate forecasts. It took almost nine hours before we were finally able to shut off the Perkins, and even then we had to be satisfied with merely crawling along at a snail’s pace, not much faster than if we were swimming alongside the boat. Oh well.

A 1:00am squall that finally brought fifteen knot winds also made for a rough night, but finally we were making good progress hauling ass at between six and seven and a half knots.

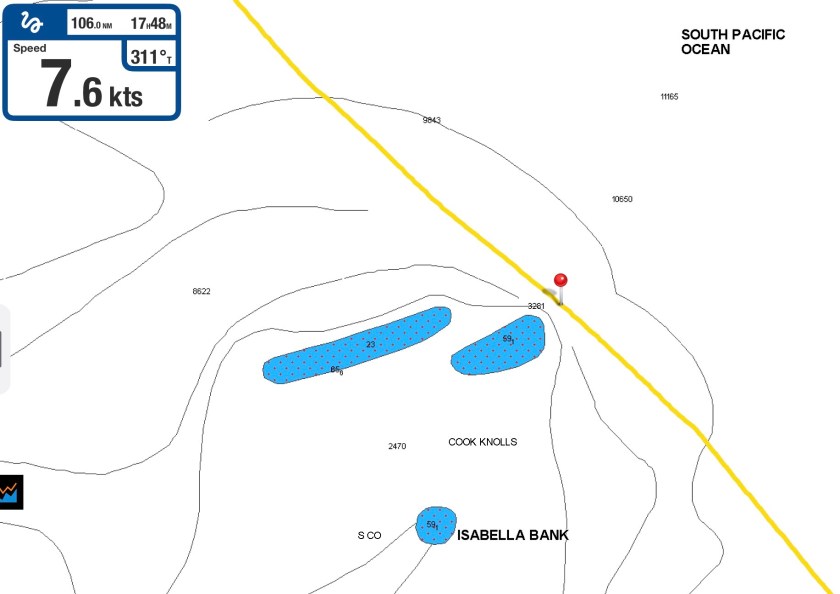

By sunrise we were passing by Isabella Bank – a massive underwater mountain whose base rests at a depth 12,000 feet. Less than two nautical miles to port of our location, it comes within sixty feet of the surface; just ten miles further west it is less than twenty five feet under water. Unbelievable.

Passing over areas like this only happens every so often.

I always envision them as holding some exotic dive secret that just begs to be discovered, like the sea mounts at Malapascua in the Philippines – one of the few places on Earth that deep-sea dwelling Thresher sharks consistently congregate at depths scuba divers can visit. Cleaning stations, mating grounds, navigational references…who knows? But it’s these underwater mountaintops, pinnacles, and sea mounts that seem to attract pelagic marine life and action.

Which is why, every time I see them on our charts, I hope circumstances allow us to stop, at least briefly.

Sometimes they turn out to be areas that create exceptionally volatile and rough surface conditions which prevent even getting in the water to take a look. Other times they prove to be a magnet for fishing boats navigating erratically as they string out nets, long lines and other implements of death – a place best avoided entirely. Sometimes it turns out they don’t even seem to exist…we actually do pass over the top and manage to jump in the water only to find nothing but blue water underneath us. Possibly real, but certainly not where the chart indicates. Or we never find out because we pass by in the dead of night.

As is often the case, multiple contributing factors would dictate whether or not we decided to stop and have a look. In this instance, we reached the Isabella Bank area just after sunrise, and Kris was still enjoying her hard earned sleep time after a rolling night of squalls and rough seas. If we were going to stop, it would only happen if I woke up Kris. Also, after struggling with uncooperative winds the day before, we were finally scooting along at seven and a half knots, an admirable speed for us. Diverting course to reach the nearby area indicated on our charts, dousing the sails, stopping Exit, and digging out our snorkeling equipment would entirely kill the momentum we had finally built up.

With a twinge of disappointment, I quickly realized that whatever secrets King Neptune potentially had hidden away under the surface were not going to be revealed to us today.

As Exit continued zipping along with full sails, our depth display never registered anything but “—“, indicating there was over five hundred feet of water beneath us though, in reality, it was probably closer to five thousand feet.

In short order, Isabelle Bank was behind us and any secrets it held remained intact.

Our first two days largely ended up being an experiment in sailing adjustments.

Sometimes settling to be content with only the solent sail deployed and a book in hand. Other times trying to harness more power from the wind by putting out both the solent and genoa, either wing and wing or trying to get them to work together in tandem stacked on one side.

The winds ranged between four and seventeen knots, the swell was on our beam, and the true wind direction wandered in almost a ninety degree arc over time. It seemed like we were continuously making endless adjustments to try to keep the sail filled.

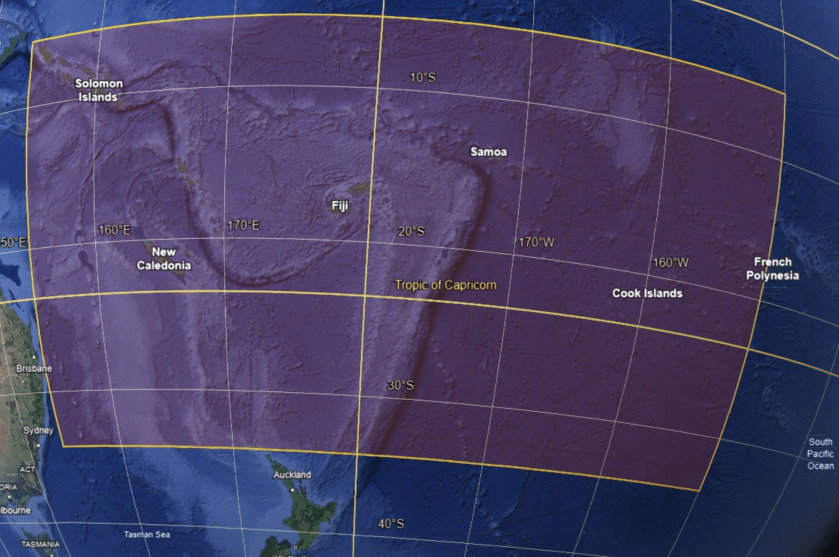

As we were preparing for our second night underway, about thirty hours and one hundred seventy nautical miles into our passage, we passed the magic number of Latitude 10°S.

Nothing obvious appeared to change; no dramatic shift occurred. However, both our insurance company and, just as importantly, history were of the opinion that we had just crossed an invisible line that meant our risk of encountering a cyclone had decreased dramatically. It hadn’t disappeared entirely, but close.

North of 10°S before December 1st. An arbitrary location by an arbitrary deadline that had loomed in the back of our minds for months like the black clouds on a temporal horizon. We had finally made it out of the dreaded cyclone box.

We both could breathe a bit easier…it was only November 26. We were actually ahead of schedule.

Still, erratic wind direction and wind speeds continued to plague us for the next thirty six hours. Our progress was good – in three days we had managed to make good on about 360nm – however, so far we had also added about eighteen hours of run time to our Perkins diesel engine.

As the sun rose. preparing to usher in the beginning of our fourth day at sea, we passed another significant milestone…crossing Longitude 180°.

180°…the International Date Line, the meridian opposite the prime meridian which together create the circle that divides the Earth into Eastern and Western Hemispheres.

Our Longitude West instantly became Longitude East.

Oddly enough, we had already been a day ahead of those occupying the Eastern Hemisphere for weeks. Tonga, though east of 180°, chose to artificially shift the International Date Line to run east of their international borders, effectively placing themselves on the same calendar day as the Western Hemisphere (and those that they have more day to day interactions with).

So, despite not experiencing a shift in the date, nor having the pomp and circumstance of an official mariner’s achievement – unlike our Equatorial crossing which resulted in our ascension from lowly Pollywogs to Shellbacks, crossing the International Date Line apparently carries no recognized maritime distinction – it still seemed rather significant to us.

Despite our progress, with almost ninety nautical miles remaining, it became apparent that we would not make it to Tuvalu until after sundown. It was also apparent that, at our current pace, we would arrive before the following day’s sunrise, an equally unappealing option.

Even motorsailing for twelve hours straight, it was still highly unlikely that we would beat the sunset. Thus, a twenty-four hour slow sail became our new strategy – a pace slow enough to assure we would have the light of a new day to guide us through the winding pass.

Just before midnight, three and a half days into our passage, we began to see a glow on the horizon…the lights of the atoll Funafuti. We were almost at the doorstep of Tuvalu.

Six hours later, the dark silhouette of Funafuti lay directly in front of us, barely left of the new day’s sun, which had just cleared the horizon line.

Amazingly, as we approached the channel, a pod of pilot whales as well as a pod of dolphins swam past us! It appeared Tuvalu took the responsibility of welcoming new guests quite seriously.

Though the mile and a half long channel looked rather intimidating on our Navionics charts, it was over a hundred thirty feet deep in places and more than four hundred feet wide.

After about fifteen minutes of high alert navigating, we found ourselves inside the main lagoon. Safe harbor North of Latitude 10°S.

It remained to be seen whether we would be able to ride out the entire five month cyclone season here…but that was a detail to be addressed at a later time.

We had arrived at Tuvalu, the least visited country on the planet.