April 28 – May 15, 2024

May 15. Thirty minutes before midnight.

In an hour and a half it will be exactly eighteen days since we raised anchor at our last anchorage fifty miles north of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. We are about to surpass one thousand nine hundred nautical miles traveled on this passage, more than twice the time and distance of any voyage we have undertaken on S/V Exit to date. Though we are almost two-thirds of the way to French Polynesia, we still have over a thousand miles of open ocean and probably at least another ten days before we will see land.

By midnight, we will have reached the latitude line of one degree north, placing us only sixty nautical miles above the Equator.

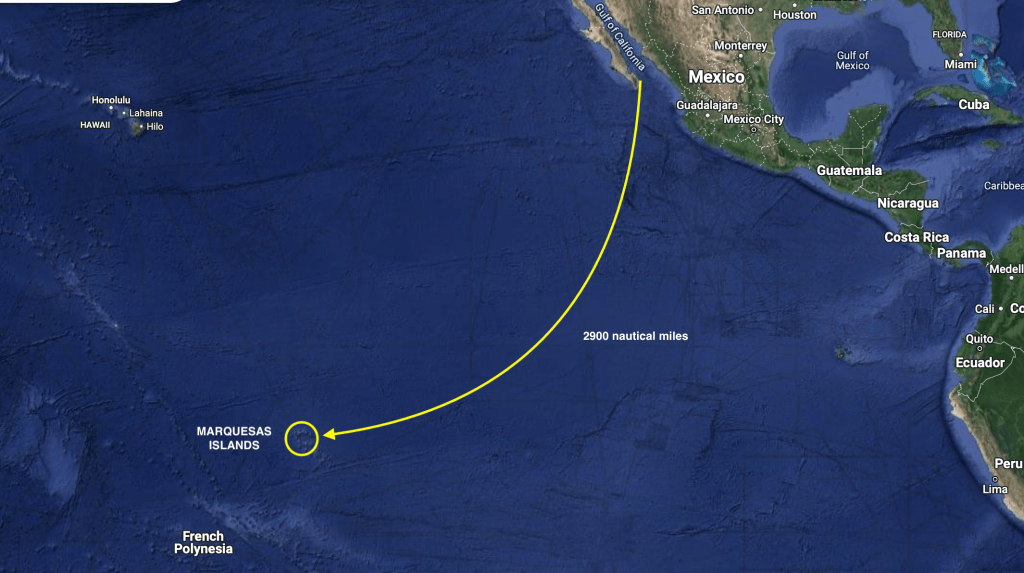

The nearly three thousand nautical miles of Pacific Ocean between Mexico and the tiny French Polynesian island of Nuku Hiva, which we anticipate to be a three to four week passage aboard our forty seven foot aluminum sailboat, has itself always seemed like a daunting distance.

Factoring in all of the steps leading up to our actual departure, all the events that took place before leaving Mexico, as well as the experiences of the past eighteen days at sea make everything all the more surreal.

While the semantics of thirty degrees of latitude to the south and thirty degrees of longitude to the west may not sound significant, every degree of progress has had to be earned.

The endless preparations required had slowly evolved, bringing us from the pure chaos of facing seemingly impossible odds, given the overall mammoth scale of everything before us, into digestible tasks and small degrees of compartmental success. Eventually, as it became harder to think of things that still needed doing than things that had been already checked off the list, we knew we were close.

The hardest part became not in determining when all tasks had been completed – it’s a boat for fuck sake – but, rather, when we’d finished what needed to be completed.

Strength and safety…no compromise, no excuses. Convenience, luxury, and cosmetics…maybe open to discussion. These are the details that can bankrupt budgets as well as prevent boats from ever even getting back in the water. The endless loop of never ending boatyard projects and/or mistaken priorities.

Having successfully navigated our way through the mine field of Exit’s arduous haul out in Puerto Peñasco, just 40 miles south of the Arizona border, which had optimistically been discussed as an expected sixty or ninety day job but, in reality, stretched out for nearly six months, finally allowed us to relinquish our temporary status as dirt dwellers and sand people (the first words spoken to us as Exit, swinging on the travel lift, was brought into the boat yard’s sand blasting lot was, ‘welcome to Baghdad’). It felt amazing be back in the water.

Exactly one month after splashing Exit in Puerto Peñasco, we found ourselves enjoying a bottle of wine on the beach in one of the bays of Espiritu Santo.

Ironically, it was the same beach on which we had enjoyed a reunion with our old sailing friend Craig from S/V Russula (nearly fifteen months prior. However, he had successfully gotten out of Mexico last season, already crossed the Pacific Ocean, and was currently in New Zealand.

We, on the other hand, had not. But we were now sooooooo close.

Our eminent return to La Paz would provide the opportunity for us to complete our final provisioning preparations needed for our own crossing of the Pacific Ocean.

As every space inside Exit’s lockers became stuffed with supplies and provisions, forecasts were studied looking for weather windows, and plans materialized regarding the logistics of getting to the tip of the Baja peninsula, which also would be a multi-step process.

Stopping just outside La Paz for a final bottom cleaning. Exit’s bottom , that is…

…then fifty miles around the northern point to Punta Arena de La Ventana. This seemed like a particularly fitting closing of the circle as it was the first anchorage we arrived at after departing the Mexico mainland at La Cruz nearly two years earlier…

…one hundred miles more to Frailes – nothing more than an anchorage that would place us less than fifty miles away from Cabo San Lucas and the tip of the Baja peninsula…

…deep breath.

A lot of steps just to reach the starting gate.

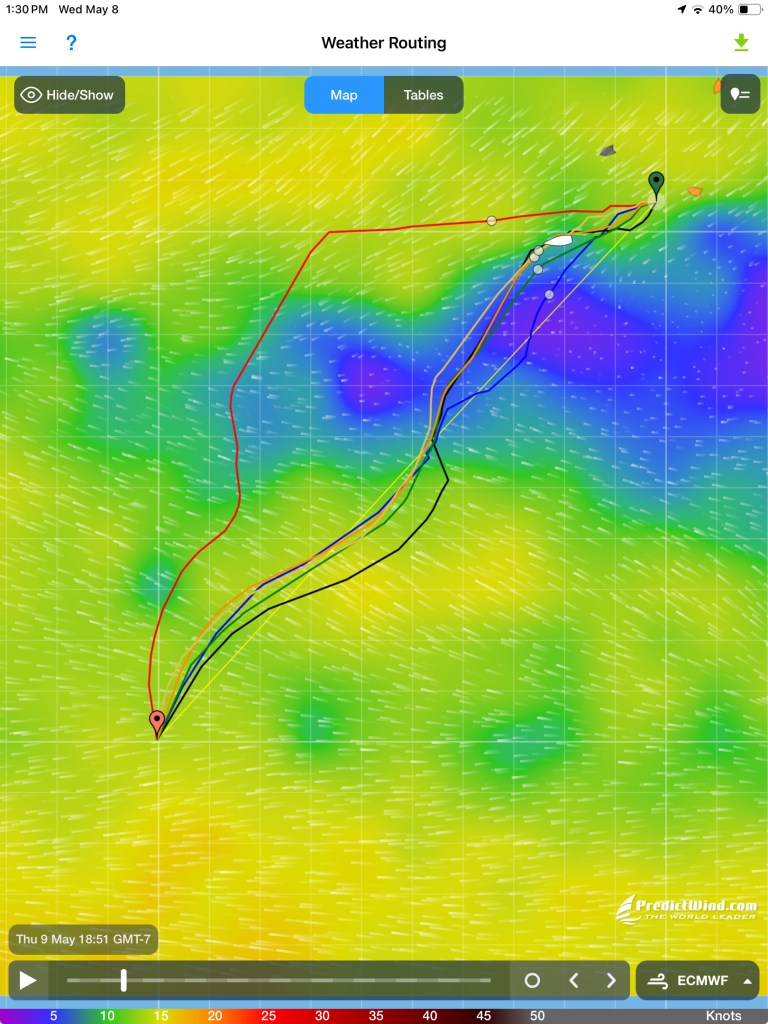

We needed a weeks worth of favorable indications offshore before committing to a start. Why a week? Because that’s about as far into the future as the forecasts would be realistically helpful. Beyond that would be a guess.

We’d been studying weather along that route for months. And Kris had accessed a wealth of information from forums and chat groups.

We needed to make our way closer to the tip of the Baja peninsula to be ready for the big leap, while simultaneously being mindful of avoiding the pitfalls of both impatience and indecision.

The longer we delay, hesitating with the indecision of awaiting a “perfect” weather window, the more we consume aboard. We could go a year without running out of canned food; but our fruits and veggies are on a ticking clock.

Conversely, impatience can quickly turn into fuel consumption…something we are now immensely aware of and somewhat nervous regarding. The two hundred thirty gallons of diesel we carry give us about a twelve hundred mile range solely under engine power, which should be more than adequate, as long as we’re not motoring half of the distance to French Polynesia. The more we can sail, the more we save fuel. Duh.

Eventually, the call was made and our official clearing out of Mexico was completed. A bottle of wine and fondue dinner at Vi’dah commemorated our final evening in La Paz, and the following morning at sunrise, Exit pulled up anchor and headed down the channel.

In a powerful moment of irony, we get a final glimpse of a dozen or more crushed boats, washed up and still stretched along the shoreline, victims of a late hurricane last year that hit while we were hauled out in Puerto Peñasco. In the end, it turned out we had been in each La Paz and Peñasco while the other was being hit harder by the outer bands of a hurricane. Sheer luck. The destroyed sailboat on the beach closest to where we had been anchored was, even more ironically, named Almost Free.

Exit, on the other hand, was finally free.

That evening we enjoyed a stunning sunset in the bay of Caleta Lobos…the precise location we had sat awaiting Hurricane Hillary almost exactly eight months earlier. So much had happened since then; it seemed like a dream now.

Once out of La Paz, we instantly switch to depletion mode. Everything we had stocked up on was now being chipped away at. We had gone through a rigorous process of asking item by item: How much can we fit? How much can we afford?How badly is it needed? How hard will it be to get?

These questions and decisions would be second guessed many times, both before and after our departure.

Initially, it felt like a stumble coming out of the starting gate. Damned if it wasn’t exactly what we’d come to expect, but it seemed we just couldn’t get a break on wind direction and intensity as we tried to make our way towards Cabo.

Despite our best efforts and some moments of great sailing, it became apparent that getting past Cabo without any sacrificed diesel was not likely going to be in the cards. Continuing to wait for more favorable sailing conditions with small bits of forward progress would probably just result in us getting completely stalled by a soon to arrive and much more definitive southern wind.

Looking beyond a genuine intent to be more green, we acknowledged that our reluctance to fire up the diesel before we even really got going was maybe more of a symbolic concern for bad omens than concern for actually running out of fuel. Better to bite the bullet, fire up the warp drive, and break free of this seeming gravitational black hole.

At 1:00am on April 28th we picked up anchor at Frailes under only a sliver of moon, and set sail for French Polynesia.

By 10:00am, the blow to our psyche of having had to run the engine for the previous six hours was offset, mostly, by the soothing silence that followed when we shut down the old Perkins. It would have been even more reassuring and soothing had we known at that moment that it would be ten full days before we would need to call upon the diesel again for propulsion assistance. Sailing good.

By noon we had passed by Cabo San Lucas and cleared the tip of the Baja peninsula. To see land, you had to look back. Outside of the Socorro Islands, which lie four hundred nautical miles in front of us, there would be nothing but ocean on the horizon for almost three thousand miles during the next month.

It would be a lie to say there was not an instant where a tingle of doubt quietly murmured deep inside…a what the fuck are we doing moment.

On a different boat…at a different time of year…with a different person…that feeling may have lingered.

But in another instant, the trepidation was gone. I couldn’t have a better partner. We couldn’t have a better boat. We had planned well and done our homework. I felt more like a fortunate adventurer than a misguided fool. It just took a moment to recognize that.

By sunrise the following morning, any sign of land behind us had disappeared completely.

Over freshly brewed cups of instant coffee that morning, we toasted having surpassed seventeen thousand nautical miles traveled aboard Exit since we purchased and moved aboard her in 2017. The milestone was actually reached during the middle of the night. However, on passage, with twenty four hour watches, nighttime shift changes tend to be more of a quick changing of the guard than a social to-do.

Our initial waypoint we had set was Clarion Island four hundred nautical miles to the southwest of Cabo. In the case of too little or too much wind, we could stop off there briefly. Part of the Socorro Islands, Clarion is uninhabited except for a friendly Mexican military outpost and occasional liveaboard dive boats. If we had good wind, we likely would not want to interrupt the momentum.

As it turned out, we didn’t have good wind. Initially it had been around ten to twelve knots but that had begun to fall off. Still, even with only a six to ten knot breeze, conditions were exceptionally calm and sailing slowly without needing to run the engine was certainly good enough momentum to keep going.

As we approached Clarion Island in the middle of the night on day four, it was an easy decision to make. There seemed very little appeal in waiting seven hours for first light before entering an unfamiliar anchorage; and even though winds were currently light it looked like there would be no improvement for days. Better to keep pressing on with forward progress.

A short time later, when we had to alter course to avoid coming within a mile of a passing cargo ship, we didn’t think too much of it. We were only hundred or so miles off shore and we had been underway for less than two days. When it happened again a week later I certainly raised an eyebrow. More than a thousand miles from anything. Plus, the second time it was just after midnight…a bit freaky. No drama; just occasional reminders to fucking pay attention.

As it would turn out, that six hundred foot cargo ship would be the last occupied vessel we would encounter in the northern hemisphere. However, even stranger was the unoccupied vessel we encountered five days later.

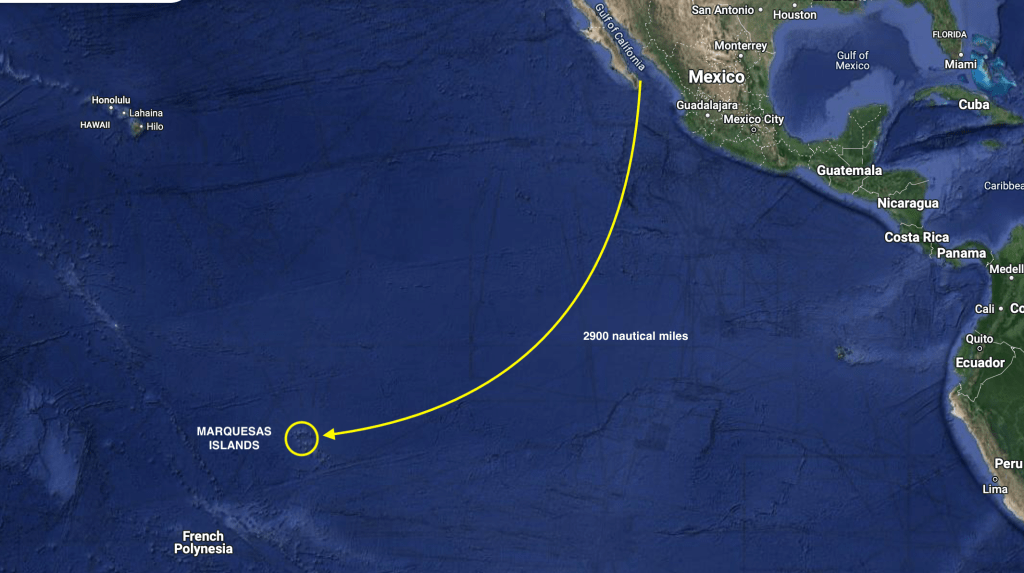

On our twelfth day underway, when a red speck appeared on the horizon, we grabbed the binoculars. It became apparent that it wasn’t a boat, but it seemed to have a sail deployed. We adjusted our own sails and came about, immediately setting a new course to investigate. As we neared, we were a bit stunned to make out what appeared to be a kayak or a SUP with a sail…? A thousand miles seemed more than a bit far out for someone to drift…? Maybe a crazy solo circumnavigating paddler…? WTF? Continuing our approach, we could slowly make out more and more details. It was a SUP-like platform that didn’t appear to have any type of hull or structure below the water; the bright red sail seemed to be attached to some kind of substantial wind vane autopilot. We tracked alongside it and had to laugh when we found a cadre of sea birds had laid claim and taken possession of what was identified on the sail as “Saildrone”.

A subsequent reaching out put us in touch with a very surprised and genuinely appreciative tech at the Saildrone company, who excitedly informed us that the units are contracted and deployed for various oceanic and weather research data gathering tasks but that they never hear back from contacts in the field. Pretty cool…but, come to think of it, yet another of the occasional reminders about fucking paying attention. Sunk by a coxless pair of boobies…hmmmmmm. Not going there…

The earlier reference to birds appearing to have laid claim and taken possession of the Saildrone may seem a bit comedic and/or dramatic…but I shit you not; some of these boobies are not benevolent beings.

First off, in our own defense, we are devoted conservationists and absolute animal advocates. No latent bird issues. We once had a blue-footed booby, a truly regal creature, aboard Exit without incident. Toured the decks, stayed the evening. Lovely chap.

But these boobies are different. Rude. Disrespectful. They fight over who gets to sit at the top of the mast and end up breaking stuff. They shit all over the deck, hatches, sails, solar panels, and isenglass windows. This went on for days. It was brutal. Exit’s log notes on May 4: “Today the Garbanzo Battle was waged and lost on the deck of S/V Exit. They have taken the mast. I fear we may be losing the Great Booby War of the Pacific.” After woefully unsuccessful attempts to dislodge them from the mast with more traditional methods like: yelling and screaming at them, pounding on the shrouds, shaking the back stay, whipping and flicking halyards at them, even running a plastic garbage bag up the flag halyard next to them to try to startle them (a ridiculously inadequate strategy), I brought out my slingshot and proceeded to start eating olives and firing the pits at the top of the mast…fact is, in fifteen knots of wind on a pitching deck I got sick of eating olives without ever making contact. No better luck with dried garbanzo beans either. I gave up before trying to harvest the little glass balls out of liquor bottle pour spouts (great ammunition but that’s a lot of drinkin’ for one bullet —- fifteen shots of liquor per shot of ammunition, literally).

On a side note, Exit undoubtably needs to address its battle readiness, both in the area of ammunition and operational accuracy.

Fortunately, the boobies inexplicably left after a few days. Even more fortunate was the likelihood of rain ahead. It was going to require a deluge or three to clean these decks.

Thankfully, within a couple of days, that rain did arrive and the booby shit which had left a disgusting white-gray-brown-yellow coat of paint on Exit’s mast, sails, and deck was finally unceremoniously cleansed.

But be careful of what you ask for.

At anchor, the rain can be inconvenient and even annoying. But underway, it can become relentless and unmerciful. In the middle of the Pacific Ocean, more than thousand miles from anything, it can be more than a little bit intimidating.

Fortunately, this was not a violent squall. The rain beat down for a bit, but we were not pummeled by vicious winds or terrifying lightning strikes. Exit received the thorough shower she needed but not much more than that…this time.

With no more boobies to deal with, I could now return to my daily task of cleaning dead flying fish off the deck without fear of being shit on. Flying fish that inadvertently land on deck and fail to flop back into the water accumulate each night. Occasionally they land near the cockpit and can be offered a helping hand. Others aren’t so lucky. Nothing startles you to full awareness during night watch quite like the loud, wet glop! of a flopping fish on the cockpit’s isenglass window a couple of feet away from your face. Well…ya, actually. Standing up in the cockpit to make a sail adjustment and literally getting slapped on the ass by a flying fish that’s just collided with your butt…that splattering shplop! makes you jump even more. I did get that one back in the water; however, he may have eventually died of embarrassment telling the tale of almost suffocating in a face full of ass!

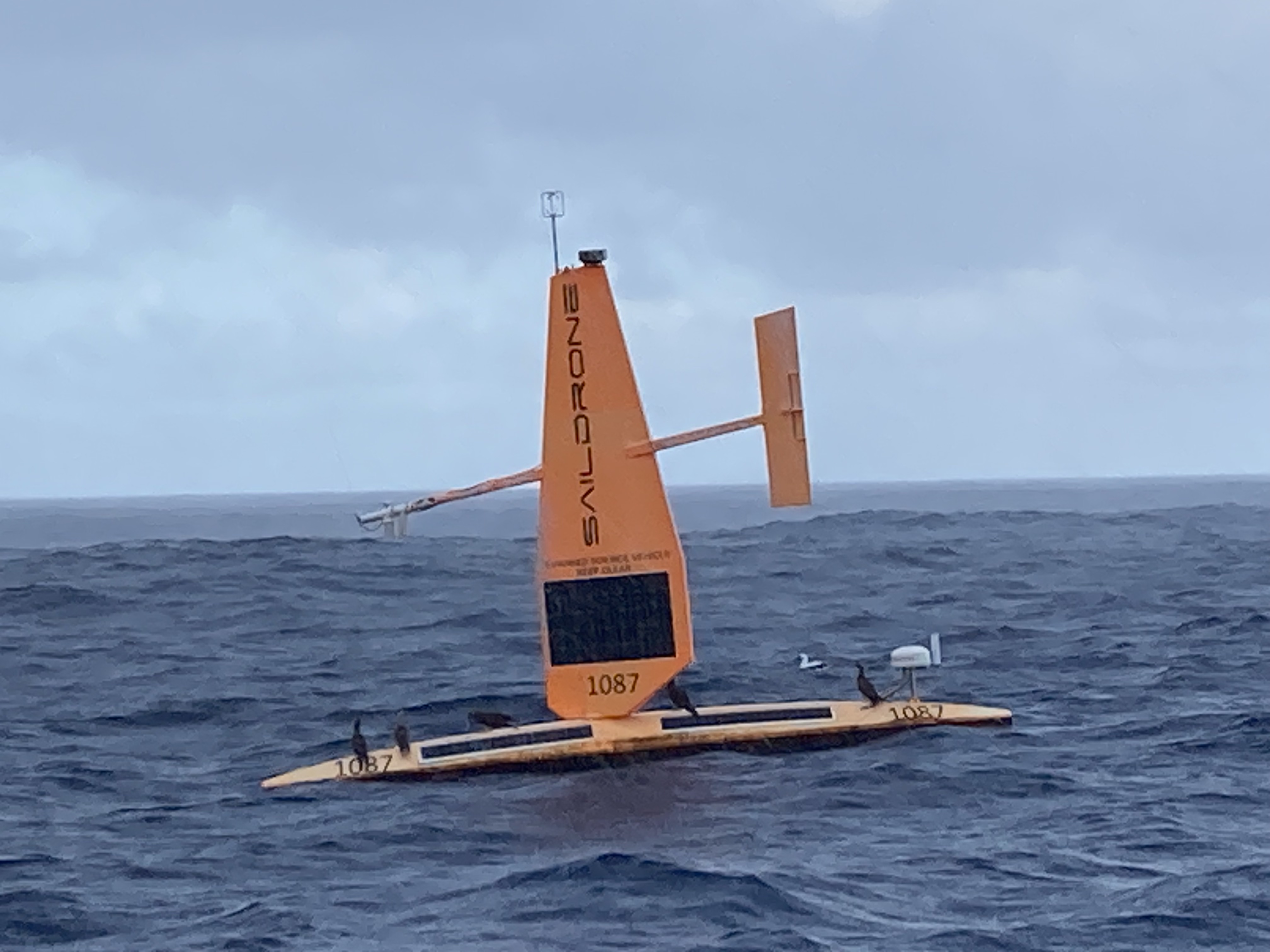

Since passing by Clarion Island our trajectory had been towards the coordinates of 10N / 120W. This was strategic.

The ITCZ (Inter Tropical Convergence Zone) is a constantly shifting corridor (right now between about 5 degrees latitude north and south of the equator) where the northern hemisphere’s clockwise moving currents and southern hemisphere’s counter-clockwise moving currents converge. Throughout that area, very light winds to no wind at all – the doldrums – are interspersed with very volatile squalls loaded with high winds and sometimes lightning.

The latitude of 10 degrees north placed us just above all that, in a position to better choose a course which would hopefully present itself to us as we approached. The 120 degrees west longitude was accounting for strong westerly currents we were encountering as we approached the ITCZ. The goal was to not get pushed too far west by these currents before getting below the equator.

We had needed to run the Perkins for about six hours to get free of the Mexican coast on our first day. Then, for ten days straight, we used nothing more than sails to propel us towards Nuka Hiva. After two weeks into our journey, we had needed fire up the Perkins for only twelve hours in total. Now, we could see a shift beginning to occur.

A comfortable downwind sail, more on the side of not enough wind than anything, with tolerable swell, began to give way to seas and winds with a bit more snarl to them.

The currents, now one and a half to two knots, relentlessly pulled us in a westerly direction. Even with four knots of boat speed, we were still having to oversteer our heading by twenty to thirty degrees just to prevent ourselves from drifting off course too far west.

As we struggled to reach our ten degree north goal before shooting well past the one hundred twenty degree west target, the Pacific went and bitch-slapped us with our first squall a thousand miles offshore. It was our first real serious rain in a couple of years and, fucking hell, did it come down in buckets. We were already double-reefed and good to go when the thirty two knot winds hit. Still…damn.

After riding that out under sail, we were dismayed to end up having to finally fire up the Perkins later when the winds died completely leaving us in sea conditions which were untenable for just sitting and waiting.

Largely, the days and nights were rather uneventful. But we found ourselves on a roller coaster of emotions. Periods of elation followed by frustration the following hour. Pondering and absorbing the magic of our current adventure only to have thoughts of weather forecasts or course adjustment options creep in, casting a shadow across an otherwise bright moment of introspection. Caught up in the indescribable and glorious colors of another sunset in the middle of an ocean, which itself had just hours before revealed an unfathomable shade of blue reflected from an over ten thousand foot depth. Serenity and colors which could never be adequately captured by even the most imaginative artist…

…only to realize our wind indicator sensor had failed. A significant blow once we determined a trip up the mast would be required before the displays in the cockpit and nav station would once again provide us with wind direction and wind speed data – something that was not going to happen until we reached French Polynesia!

During the next four days we found ourselves having to motor for over forty hours as we battled to get through the ITCZ. At times there was absolutely no wind, but the relentless western drift and lumpy sea state still prevented the option of just sitting and waiting things out. Other times we were beating thirty degrees into fifteen knots of wind from the south.

All the while, every weather forecast indicator told us that we were currently at the greatest risk for heavy lightning and potentially violent squalls, keeping us in a constant state of high alert and concern. Every possibility and scenario was playing out again and again in our heads. Every decision was being second guessed.

Fortunately, we dodged the lightning…but slogged through lots of rain…and lots of threatening black clouds which we attempted to navigate around as much as possible.

Finally squeezing below the latitude five degrees north after two days of sporty conditions, Exit’s logbook notes: The ITCZ…last night was fucking wet…with the sun coming up it looks like Mordor ahead…milk run my ass…just cued up ‘Riders On The Storm’ on the stereo...

Before departing Mexico, we had envisioned possible situations of absolutely still air combined with mirror-like flat surface conditions…sit or motor. The doldrums. Like the movies would portray “becalmed”. But motoring into winds, fighting currents, four foot waves coming across the bow…not in the brochure.

The nights were now pitch black. Almost no moon, and clouds that would obscure one if it existed anyway. We kept receiving daily reports of a derelict sailboat that had been spotted adrift three weeks ago within a hundred fifty miles west of our current location. Remnants of a dis-masted and abandoned boat from over a year before. We’d never see it at night even if it was next to us. Fortunately, we knew a drifting boat wasn’t going to get any farther east in the short term to potentially be a threat with these currents…as long as we could stop going west, it wouldn’t be a concern.

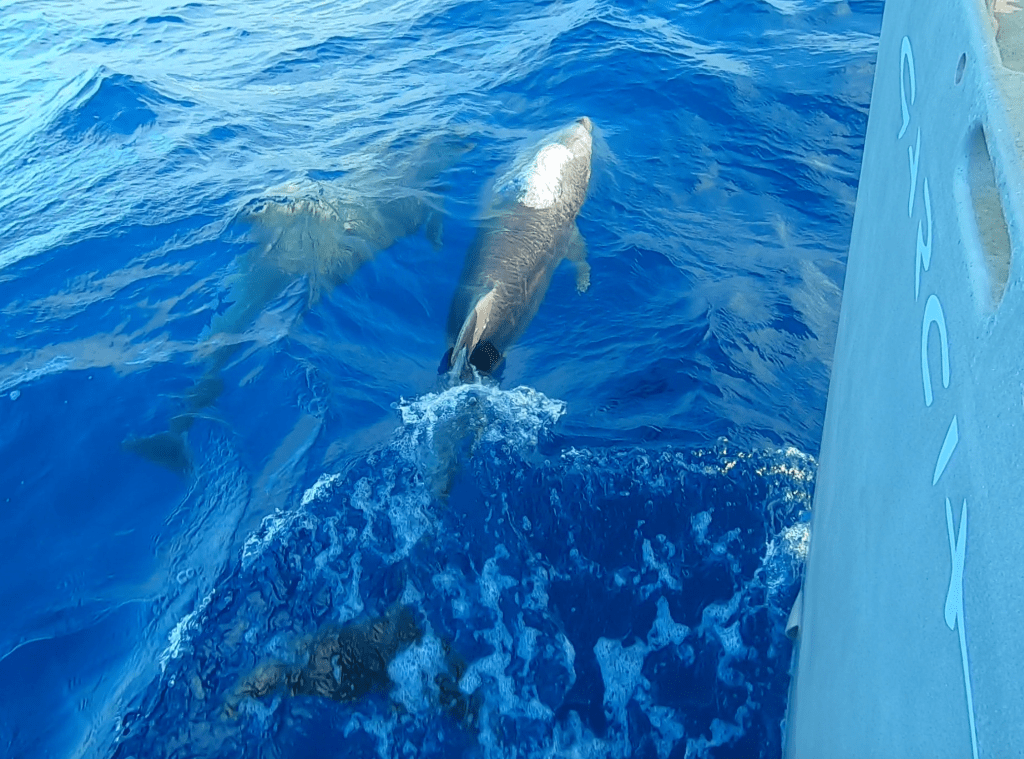

On day seventeen we were visited by the first pod of dolphins we had seen since departing Mexico. Our friends stuck around for quite a while doing gymnastic leaps out of the water, surfing down wave faces, and jockeying each other for position bow-riding Exit.

The visit was received as a very good omen. It seemed as though, as we closed the gap between Exit and the equator, every degree of latitude had gotten more and more difficult to push through; each number approaching zero harder and harder to reach. All the while, we relentlessly continued our western drift.

Tenacity and determination eventually helped tip the scale in our favor. As another midnight came and went, ushering in day nineteen of our passage, we watched the numbers on our chart plotter representing the coordinates of our current position flash by until…boom. The number”1” on the latitude reading changed to “0.999”. This placed us only “minutes of latitude” away from the big red line!

The Equator. Less than one hundred nautical miles away.

Translated into sailing speed that means…looks like we may get a visit from King Neptune tomorrow right around happy hour! Woohoo!