May 16 – 27, 2024

Crossing the line.

More typically a reference to something inappropriate I have just said or done.

However, in this case, crossing the line represented a significant accomplishment of honorable achievement. A monumental leap in our sailing evolution…Neptune’s recognition of our ascension from the ranks of lowly “Pollywog” to noble “Shellback”, having just successfully sailed across the Equator.

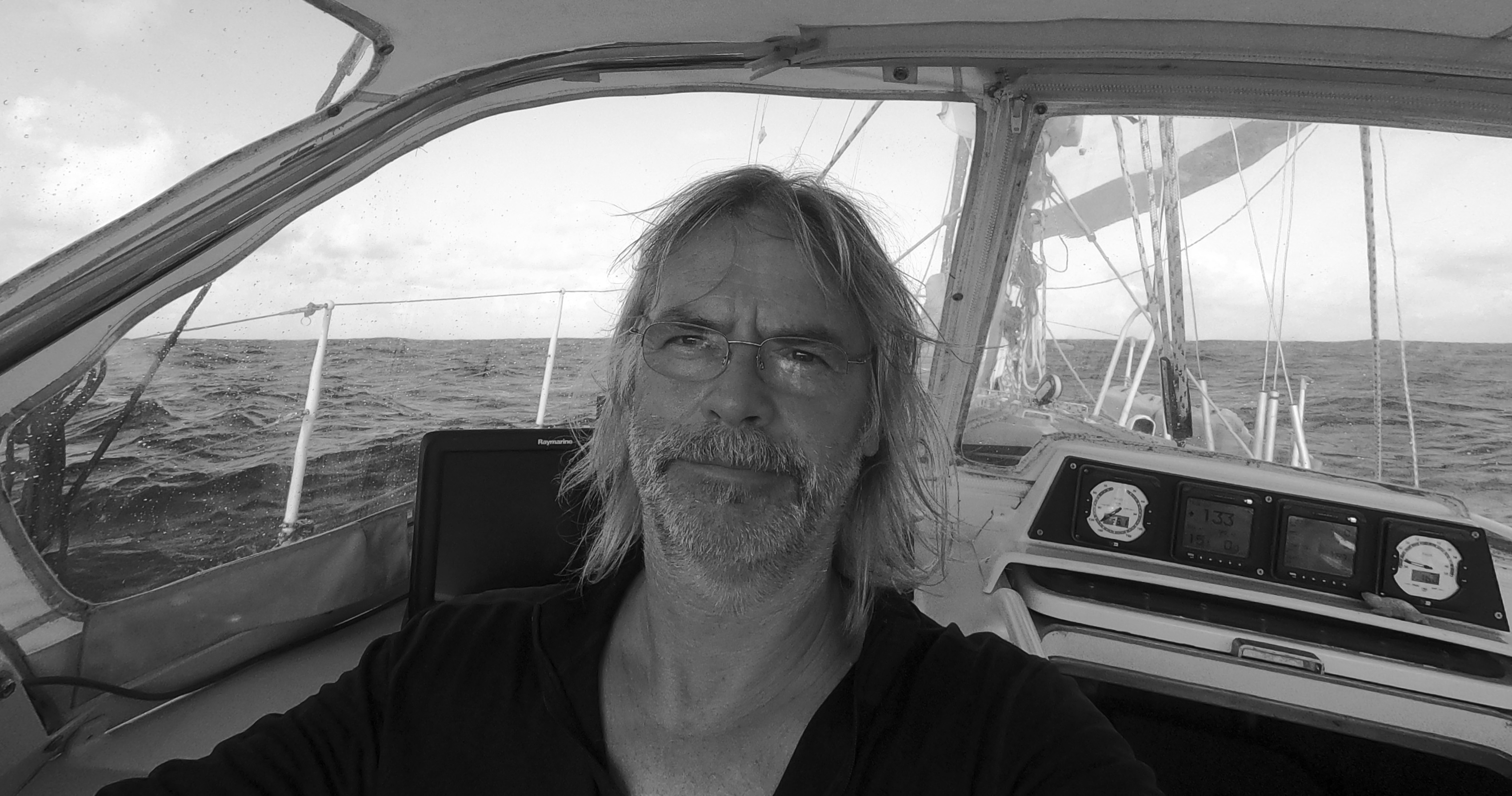

There is a certain feeling of complete isolation aboard a (relatively speaking) tiny boat in the middle of a (by pretty much any standard) damn big ocean.

I was stunned when it occurred to me that the closest people to us were on the International Space Station. It seemed unfathomable as the thought bounced around inside my head; but then again, there’s a lot of space in there as well. Amazing? Well, maybe not really… it sounds quite impressive; but then I found out the Space Station is actually orbiting only about 250 miles above us. Hmmm.

A hundred years ago we would have been in a boat without even electricity, much less the advanced technologies we enjoy. Forced to glean weather information only from what could be seen on the horizon. Dependent solely upon one’s internal expertise and accuracy in celestial navigation and reading archaic paper charts to find your way across a vast ocean while, simultaneously avoiding become one of thousands of shipwrecks, dashed hopelessly upon uncharted reefs, barely submerged rocks, or unseen islands scattered haphazardly in your path.

Here in the twenty first century, on the other hand, we have the luxury of GPS, electronic charts which display our current position in real time, electronic navigation equipment, even autopilot. Different times for sure.

And n0w there is Starlink. Surprisingly, at an altitude of about three hundred fifty miles, the Starlink satellites orbit almost an extra hundred miles above even the International Space Station, supporting what has turned out to be one of the most important technologies we have aboard Exit. Yes, Elon Musk is a disgusting human being and complete piece of shit. He has single-handedly brought back a higher stigma to being a rich, white South African than has existed for forty years and I absolutely despise contributing to his ever-increasing wealth which seems to expand at a rate faster than an exploding supernova. Yet, for us Starlink has been an absolute game changer. It’s not simply about the convenience of getting online anywhere we are on the planet. Ultimately, it’s more about how this technology has exponentially increased our safety.

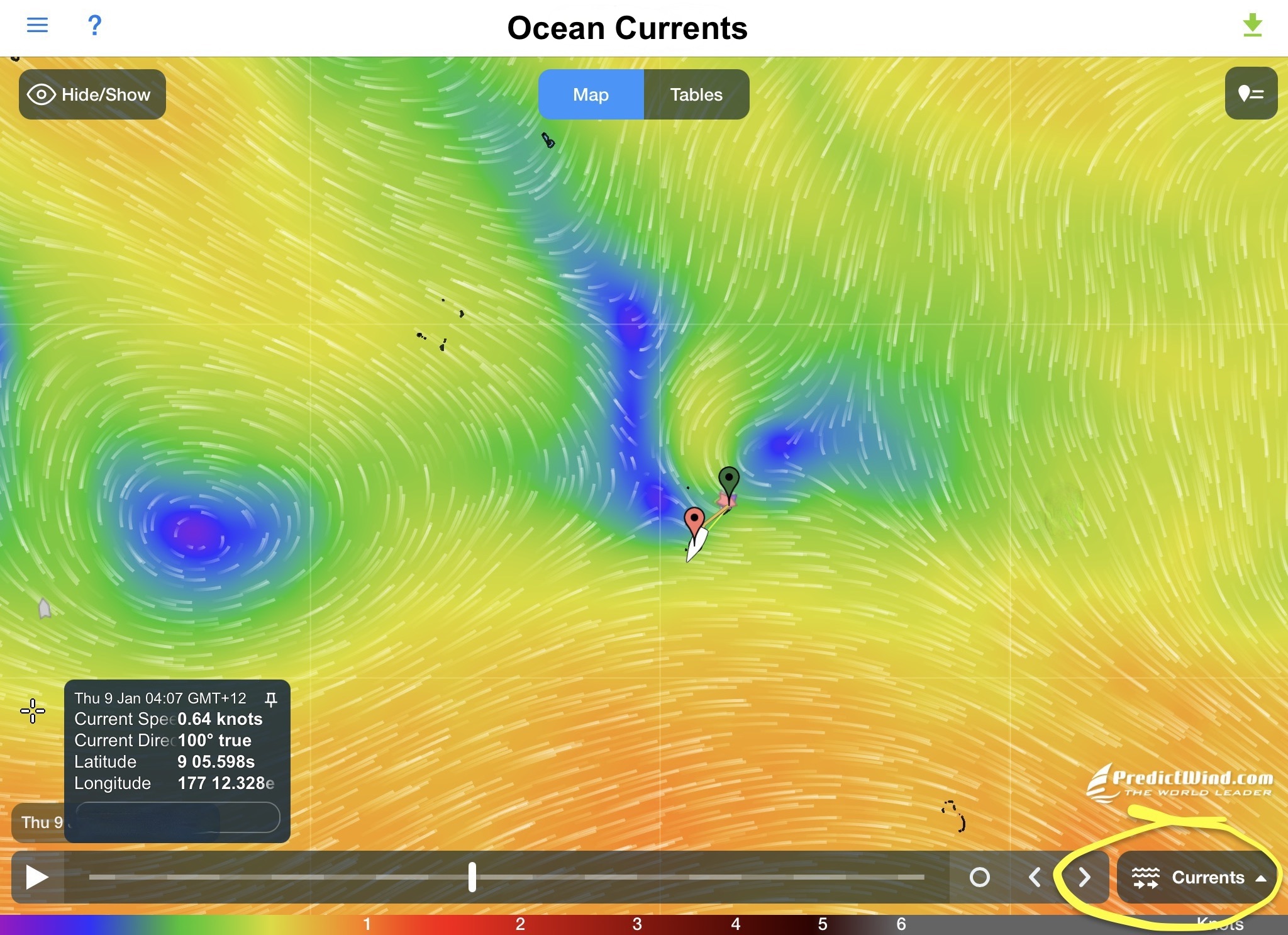

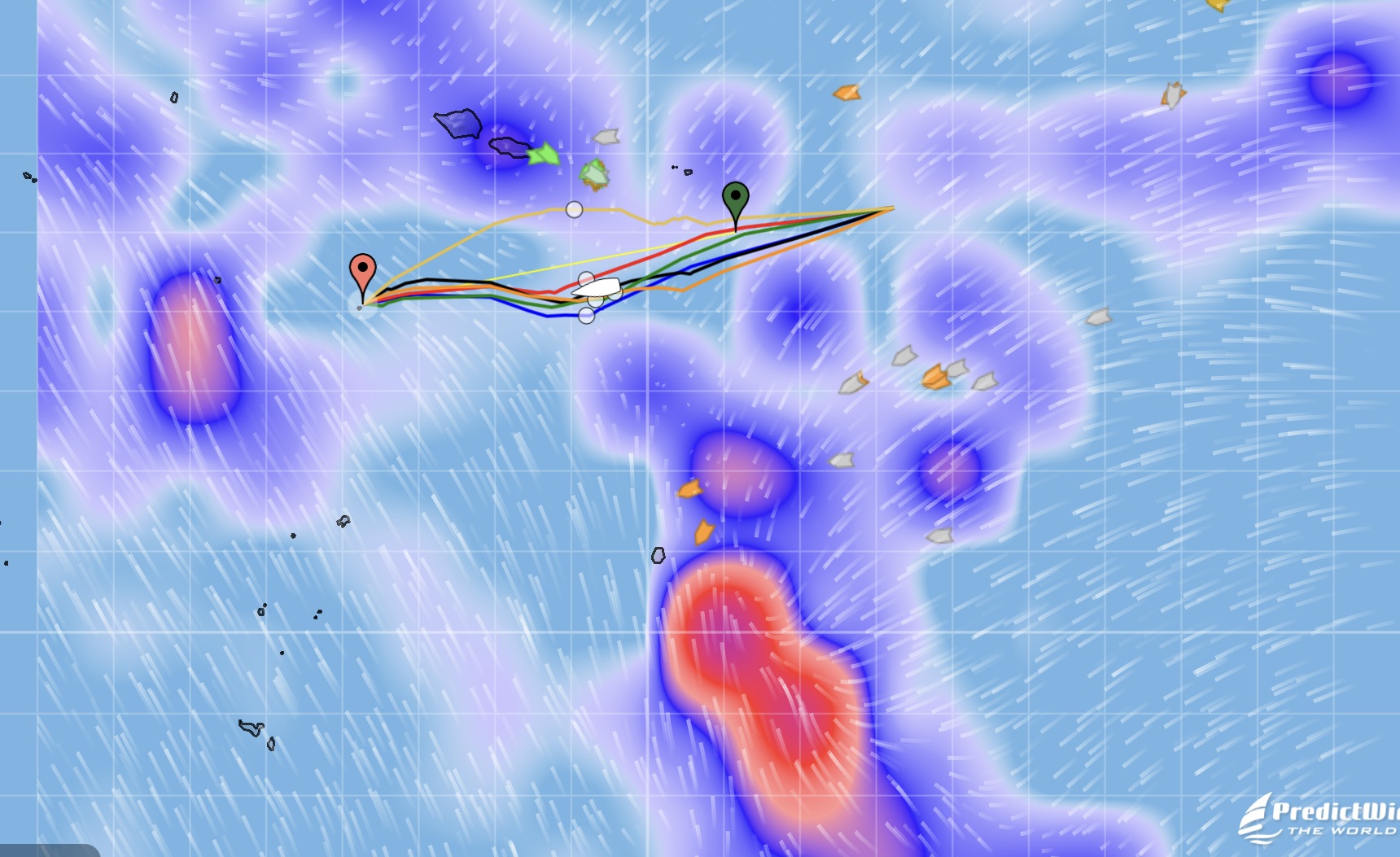

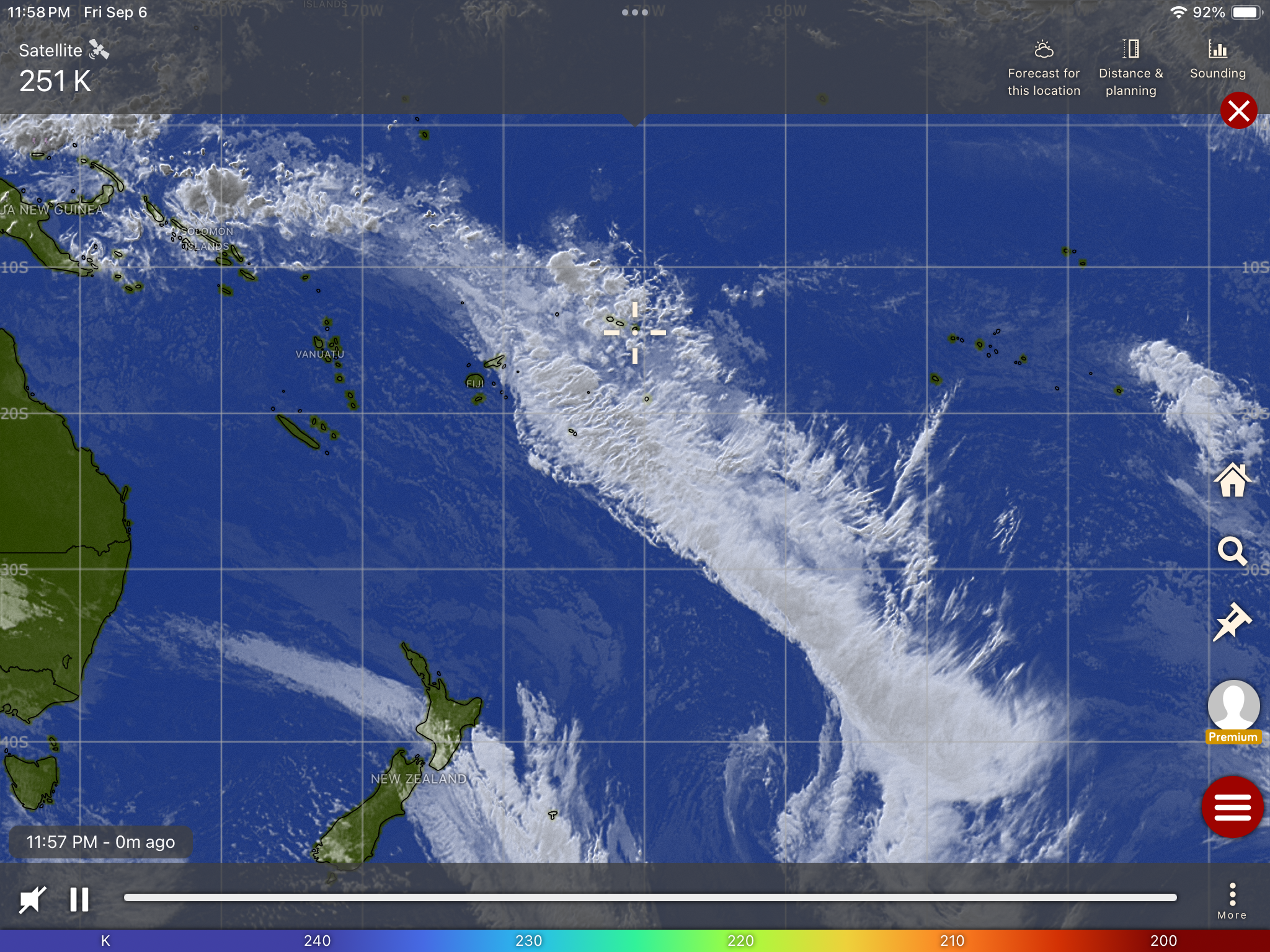

Even a thousand miles from the nearest anchorage, with Starlink we are able to instantly access numerous sources of weather data and forecasts which are updated multiple times each day. These can be forecasts of wind direction and wind speed, both sustained and gusts; forecasted ocean currents; forecasted rain and lightning; forecasted wave height and interval; tidal times and heights; NOAA weather warnings and hurricane/cyclone tracking; even real-time satellite imagery of clouds and precipitation (which distinctly reveal squalls and storms that forecasts may have missed).

The limitations of having this information only at our current location, which our on-board sensors and instruments provide (or twenty four miles out in the case of our radar aboard), are obvious. On the other hand, more complete, more accurate, and more current information over an unlimited range of distance not only make us undeniably safer, but also lead to higher levels of confidence and success in our decision making ability.

This makes an enormous difference in being able to judge and strategize departures and arrivals at certain locations, avoid squalls while underway, make adjustments to our trajectory to accommodate changes in weather along the way, as well as just sleeping better having made better decisions with more complete information.

Communicating with friends and family; chatting with other boats in real time; surfing the Internet for news – all icing on the cake. Of course, there always has to be an awareness regarding power consumption…underway we limit how often we turn it on.

In the end, the truth remains that despite possessing the best and most scientifically determined forecasting information in the world, it is still exactly that – a forecast. Not a schedule or itinerary. Sometimes Mother Nature just says “Fuck you, your forecast is flat wrong”.

And though, your departures, arrivals, and chosen headings (especially for shorter distances) may have been optimized, when you’re in the middle of nowhere, thousands of miles from anything, days or weeks into a passage with days or weeks to go before you have any other option than keeping going, the fact is you just get what you get and deal with it. There’s no time outs, do-overs, or restarts.

Approaching the Equator we had been more than lucky in avoiding all but a few squalls which had knocked us about a bit, but had turned out much less significant than they could have been.

For nearly two weeks straight, after losing sight of the Mexican coast behind us, we had propelled ourselves forward utilizing nothing more than the power of the wind in our sails. Only six hours of motoring and three hundred thirty hours of sailing. One thousand four hundred nautical miles. We were pretty proud of that.

But as we approached the ITCZ (Intertropical Convergence Zone), things had changed drastically. We had few options. Sitting around in calm water patiently awaiting a breeze that would inevitably fill our sails once again had sounded good during the planning stages. After all, we were on no time schedule.

However, sitting uncomfortably in a rolling swell hoping ominous black clouds that announced the potential arrival of torrential downpours and fierce gusting winds would keep a respectful distance was seeming less and less like a smart strategy. Furthermore, the very real possibility that those clouds also could harbor and unleash terrifying barrages of lightning seeking out electrical conduits to transfer their millions of volts of electricity to the Earth made the idea seem even dumber, especially with our sixty foot metal mast being the only thing higher than the waves for hundreds of miles in any direction.

With that reality firmly taking hold in our psyches, we had realized compromise was in order…screw the ideological purity of zero fuel consumption and get the fuck across the Equator.

For four days in a row, over the course of five hundred nautical miles, we motorsailed forty three of the one hundred hours.

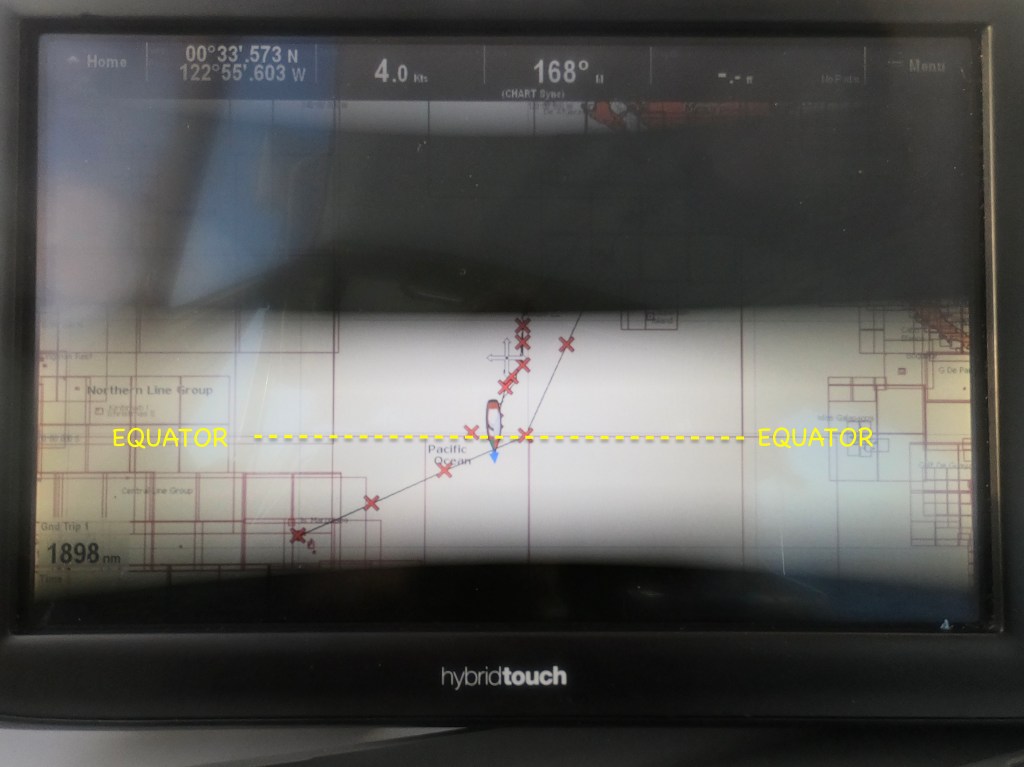

But now we were on the verge of reaching the Equator. Not long after midnight on May 16, we had crossed the first parallel north, placing us sixty nautical miles above the Equator Line. So close.

We continued on our southern heading. As the sun broke above the horizon line heralding the dawn of another day, we had halved the distance…barely more than thirty minutes of latitude remained.

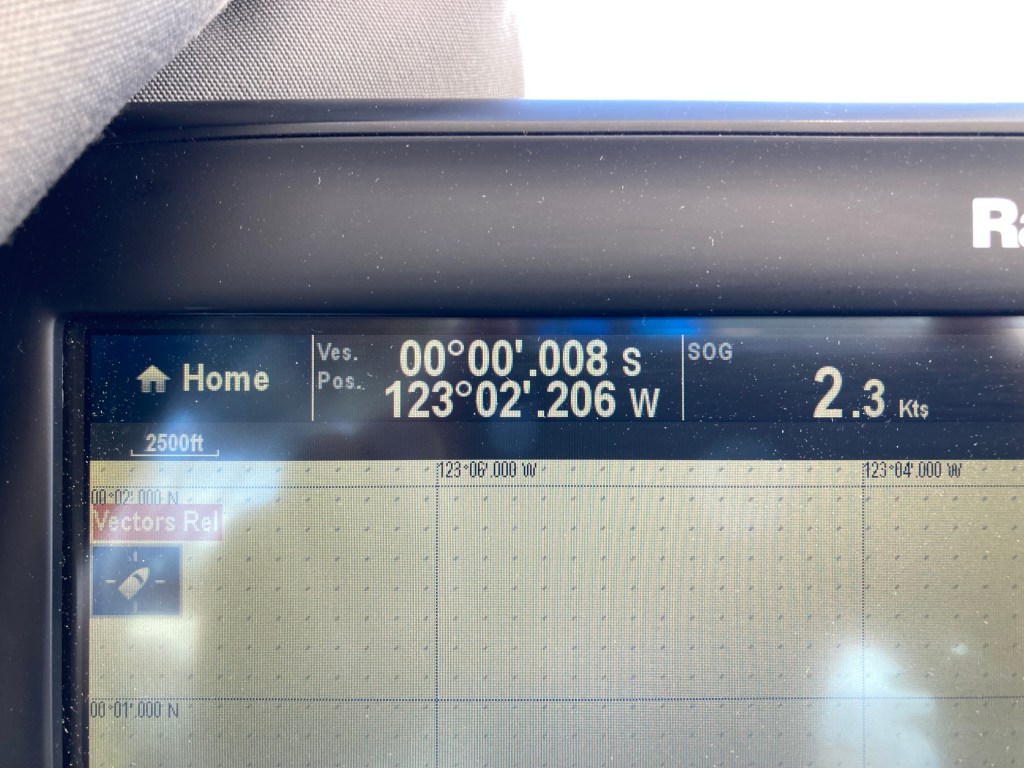

By 3pm, the GPS coordinates on our chart plotter were displaying “0” degrees and “0” minutes of Latitude North, ticking down the final hundredths of seconds towards zero. As we scanned the water in front of Exit, seeing no large sign nor visible line we joked that the Equator itself seemed quite ambiguous and wondered exactly how the moment would have been realized prior to the invention of GPS. Maybe there used to be a sign back then…

Crossing the Equator…the moment when Latitude North becomes Latitude South.

Maritime tradition dictates that sailing across the Equatorial line results in a sailor transforming from a “Polywog” to a “Shellback”…a sailing achievement of great significance. Though we did not go so far, which some do, as to don costumes and participate in a massive production including an initiation ceremony administered by other “Shellbacks” (alas, we are the only two people aboard our noble vessel), we did celebrate the event with a proclamation to King Neptune as well as an offering of precious Kraken rum.

This was followed by a baptism swim in the Pacific Ocean, where we each swam across the Equator, ten thousand feet of water below us, followed by a toast with our own shots of Kraken rum in celebration of our transformation from “Polywog” to “Shellback”.

Momentarily, for a split second, the latitude coordinates read “00°00′.000”.

Then, for the first time in three weeks, since we had picked up anchor at La Ventana in Mexico on April 25, the chart plotter coordinate numbers began to increase again. What made that even stranger was the fact that we were still on a southern heading. The difference was there was now a “S” after those latitude coordinates instead of a “N”.

Nothing else seemed different. But we felt different. We were now “Shellbacks”.

That evening King Neptune gifted us perfect sailing conditions and Mother Nature painted a brilliant sunset for us to enjoy as we continued our journey into the Southern Hemisphere.

The following morning we had to fire up the Perkins engine yet again; however, it would constitute the final six hours we would need the diesel for propulsion until we were lowering our sails as we made landfall ten days later in French Polynesia.

That afternoon, on our twentieth day at sea, we sailed past the two thousand nautical mile mark during this voyage. Twenty hours later we had another brief celebration as we realized we had just surpassed nineteen thousand nautical miles traveled aboard Exit in total during the previous seven years.

Over the following days, we began to notice a significant change in the conditions. The ominous dark clouds which had threatened us continuously for the previous week began to give way to more and more blue skies. The currents, with which we had been relentlessly struggling, now seemed to be working in our favor. The overall sea state just felt more benign…more cooperative.

That’s not to say that Murphy didn’t have something to say about things. Eventually, he spoke up and reminded us of his law.

After twenty four days of nearly 24/7 operation, our electronic autopilot, who goes by the (usually) affectionate name of Jeeves, decided he had had enough and demanded a night off. This was at 21:12, at night of course, as it often is. The biggest problem with Jeeves is that he gives us no notice that he is taking time off. The first indication we get is a shrill panic-inducing alarm that announces no one is steering the boat any longer…holy shit! Even with someone in the cockpit, there is a moment of frenzy as the person on watch makes a desperate scramble for the wheel.

If conditions are bad, or we are both momentarily below-decks, this can be a near heart attack inducing event.

Fortunately, this time neither was the case and control was quickly restored without incident. For just such a contingency, we have Schumacher – our backup electronic autopilot. Not nearly as sophisticated as Jeeves, but a solid worker and generally more reliable. Within about five minutes, we had Schumacher rigged up and he was happily in control of the helm.

Shortly after sunrise the following morning we were treated to a double rainbow. Later, in the afternoon, Jeeves was back on duty.

Then, just as it looked like the day would go down in the books as a winner, a squall hit us hard. As we were starting to reef the genoa sail, the furling line somehow ended up slightly tangled against a sharp edge, and within seconds had chafed itself all the way through. Instantly, with no tension on that side, it unfurled out all the way and started flogging madly in the ferocious gusts that had picked up.

There was far too much wind to leave the massive 130% genoa sail out, which would have dangerously overpowered Exit, but there was only about ten feet of furling line remaining – not even close to enough to reach a winch which would be required to get the sail in under these conditions.

In a moment of blind luck, it occurred to me that the anchor windlass at the bow of the boat just might work. I grabbed the windlass remote and rushed to the bow. There was just enough line to wrap around the drum of the windlass. I pressed the remote button, the drum began turning and, lo and behold, the genoa sail began furling in. Whew…crisis averted.

Our heart rates had returned to normal by the time the squall subsided. Eventually, we were able to dig into the aft lazarette, retrieve the old furling line from among the lines we had kept as spares after replacing all the running rigging during our haul out, and re-run it in place of its short-lived replacement.

The following three days were much more uneventful. Just brilliant sailing conditions running at about 130° in mostly eleven to seventeen knot winds, with six to ten foot seas at a comfortable interval, averaging five to seven knots of speed. No squalls. And with the lunar cycle almost reaching a full moon, the nighttime visibility had become much more pleasant. What more could we ask for?

On our twenty-eighth day at sea, we noted in Exit’s log that we had begun to see many more birds over the past twenty four hours. It could mean only one thing…

“LAND HO!” was the cry late in the afternoon.

It was ‘Ua Huka. French Polynesia. One of the islands that makes up the Marquesas. Not our destination but less than forty miles separated ‘Ua Huka from Nuka Hiva, the island we were going to clear in at. We were almost at the front door.

We brought in the sails a bit and slowed our speed with the intention of arriving at Nuku Hiva just as the sun was rising. Considering how long we had already been at sea on this passage, waiting a few extra hours for the peace of mind of entering an unfamiliar anchorage with the benefit of daylight was a no-brainer.

May 27, as the sun slowly rose, the night’s sky transitioned to a shade of indigo, gradually fading from purple to orange and finally yellow at the horizon. The gentle swells of the Pacific began to appear as the night’s shadows began to give way and contrast with the reflecting light and colors from the sky.

We had just surpassed twenty thousand nautical miles aboard Exit since purchasing her in 2017.

As the new day’s light began to better illuminate the surrounding lush green peaks which comprise Nuku Hiva, we entered Baie de Taioha’e – the bay nestled up against Nuku Hiva’s main town, Taioh’e. We had to clear into French Polynesia, and in the Marquesas Island group, Nuku Hiva was one of two places we could do that.

At 6:45am we dropped anchor.

The passage had taken us twenty nine days, five hours and fifty five minutes.

Three thousand one hundred twenty six nautical miles in total.

We were exhausted both mentally and physically, but we had made it to French Polynesia.